Will Property Prices Remain High In 2023? Here’s Why A Property Undersupply May Prop Up Demand Despite The Economic Uncertainty

Get The Property Insights Serious Buyers Read First: Join 50,000+ readers who rely on our weekly breakdowns of Singapore’s property market.

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.

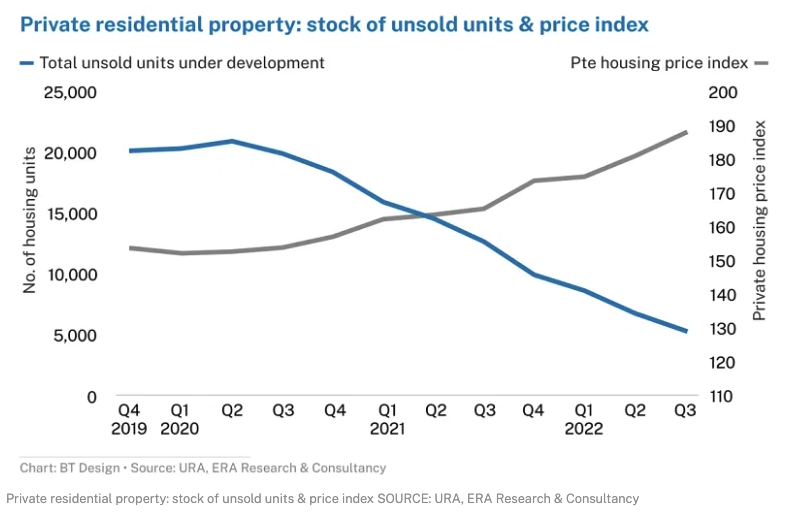

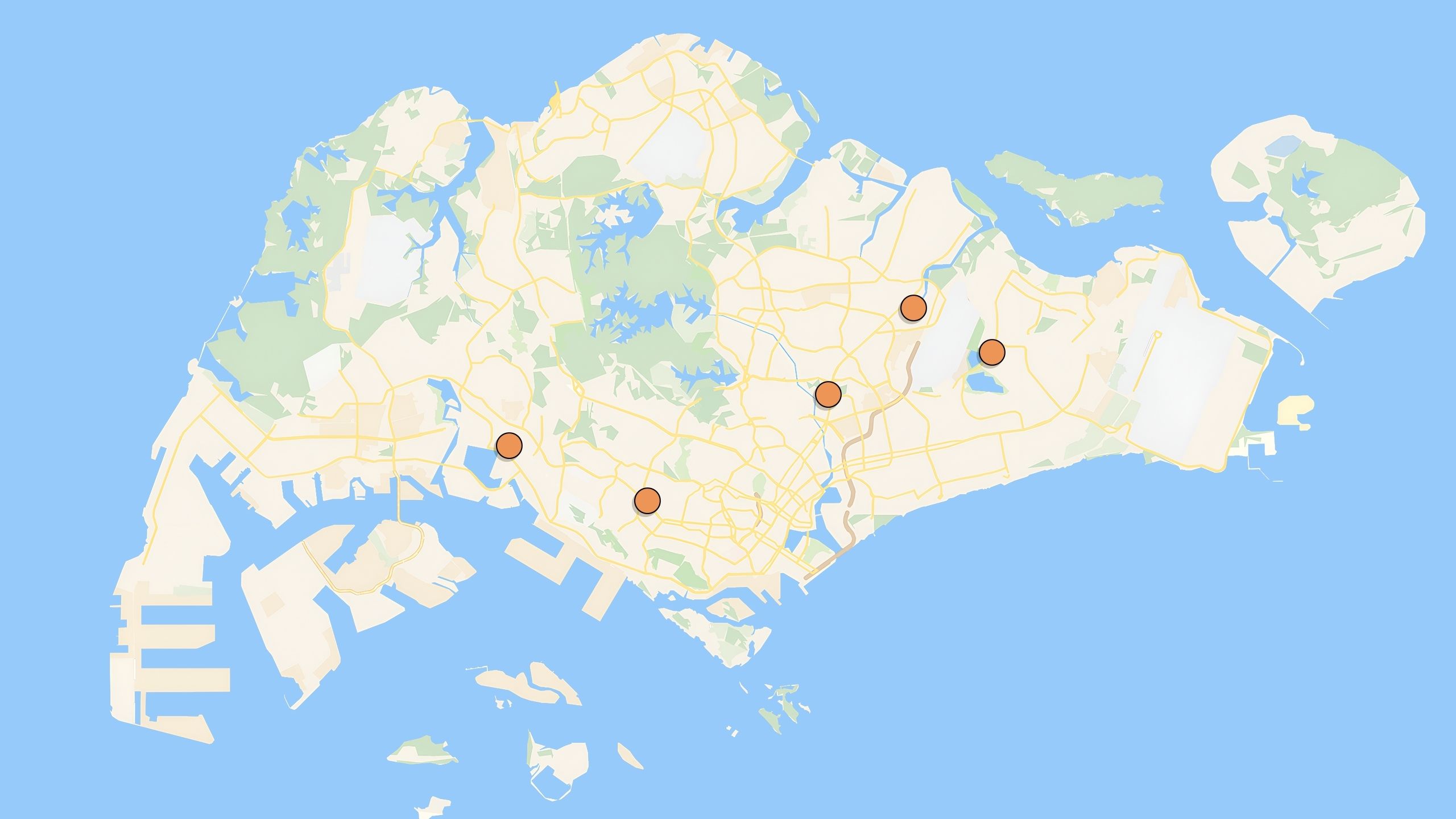

Every five years, there should be a cycle of en-bloc sales where property developers replenish land banks, and put up new developments. The last bout was in 2017; so why aren’t we seeing a major one in 2022? Compounding the problem is the low supply of housing; dwindling to its lowest point in around 15 years. At this rate, how is there hope of scarce private housing dipping in price even next year or even after?

A dramatic reversal in the housing supply

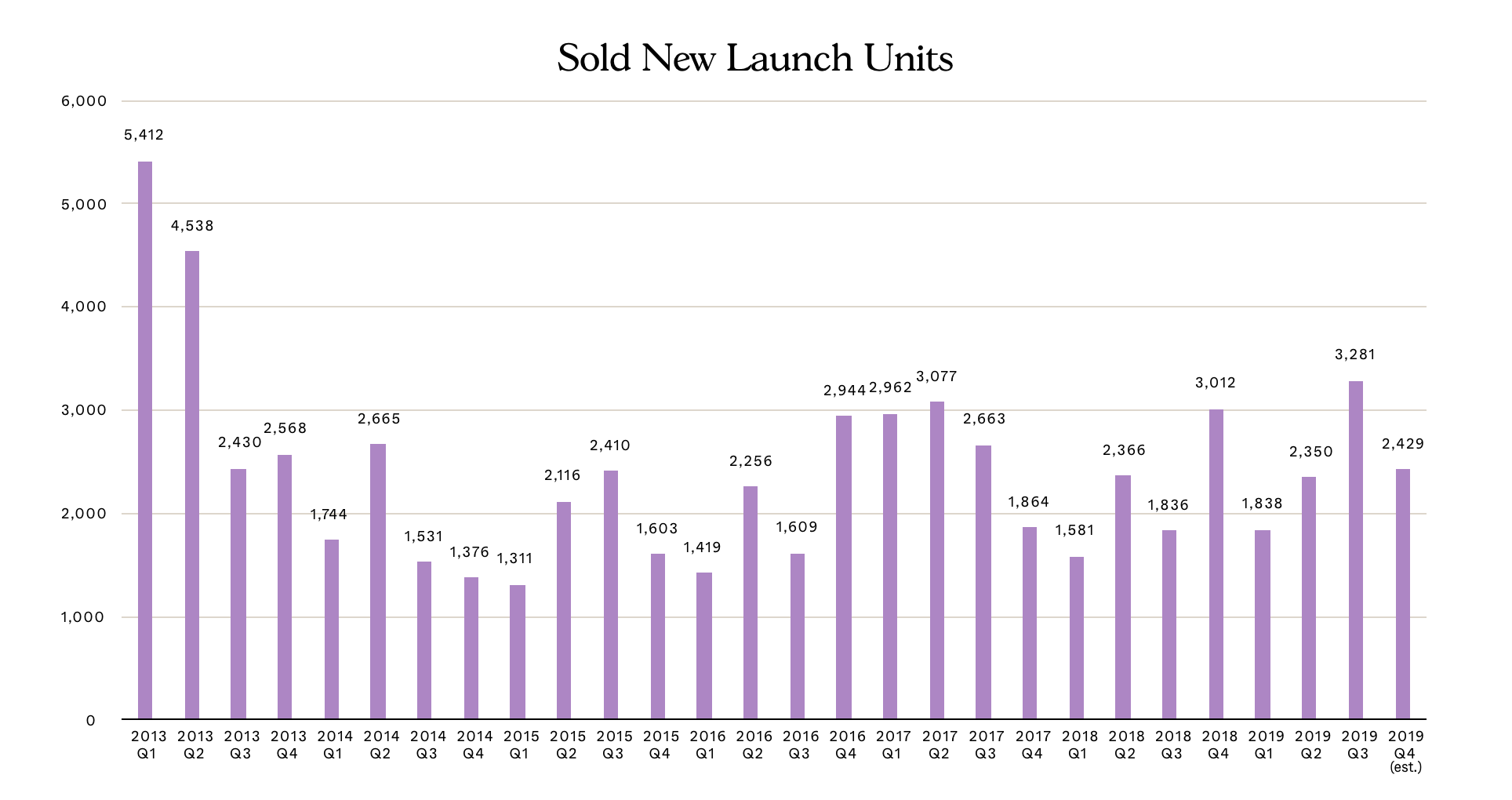

It’s hard to process the sheer speed at which we went from a supply glut, to critically low inventories of unsold housing. To put the situation in perspective:

At the end of November 2019, analysts warned of an oversupply situation with 31,948 unsold homes. There were even calls for cooling measures to be reduced to move these units, and the consensus was that it would take three to four years to clear the supply glut.

This was, at the time, the consequence of the 2017 en-bloc fever, which saw numerous foreign developers with deep pockets pushing into the Singapore market.

That year, the apparent takeaway was that we need to be cautious about en-bloc surges. In fact, development charges had already been raised since September 2018. While the government didn’t explicitly say it was to cool the en-bloc fever, it was quite easy to connect the dots.

Fast forward to December this year, and the situation has seen a complete U-turn. There was no “three to four-year” wait to clear the inventory; most of it was snapped up right in the aftermath of Covid.

To date, the supply of unsold housing has fallen for nine straight quarters, with ERA Research and Consultancy reporting around 5,320 unsold units. This is the lowest number since 2007, when at one point we saw just 4,666 unsold units.

Developers seem hesitant to commit to new projects

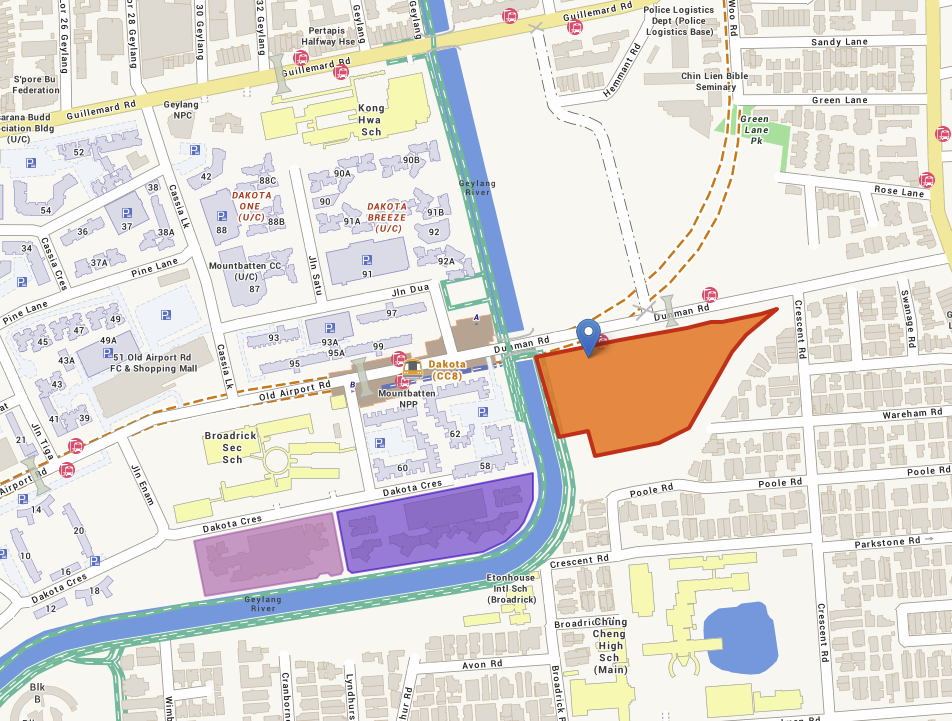

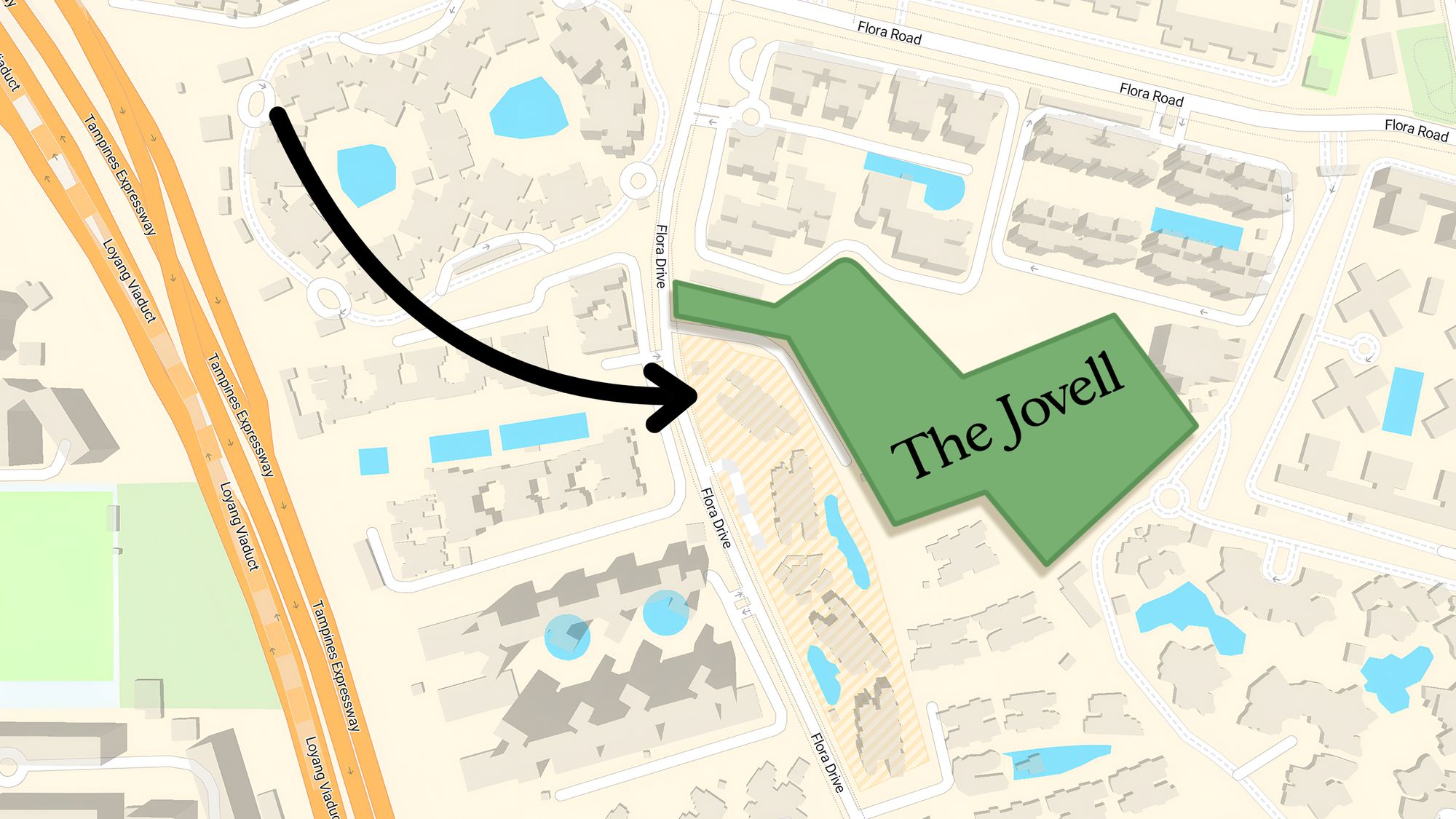

From the list of upcoming new launches that may be coming up in 2023 so far, this seems to be just under 30 – which is a far cry from the number of launches in 2020/21. It’s not just the number of launches, it’s also the sizes of the new launches, as few are like the mega-developments we’ve seen in recent years: the 1,000+ unit condos such as Normanton Park, Treasure at Tampines, D’Leedon, etc. long since sold off their last remaining units. (Only one so far possibly above 1,000 units, the estimated 1,040 unit Dunman Road GLS site that was bought by SingHaiyi).

What’s becoming clear is the growing hesitance of property developers. Consider the Hillview Rise and Bukit Timah GLS sites this year: despite Hillview Rise being near an MRT station, it got only four bids. The Bukit Timah Link site – which should have been an easy deal given its small size – saw only five bids.

This is despite developers facing depleted land banks, and the last tranche of condos from the 2017 en-bloc sales having been sold in 2021. Recall that traditionally, there’s a 10-year cycle as developers buy, rush to build and sell before the ABSD deadline, and then start buying again. This has now been seemingly shortened to 5.

Even with regard to en-bloc sales, word on the ground is that progress is slower than expected. We did see one or two significant en-bloc deals this year, in the form of Golden Mile Complex which was sold to a consortium of developers, and Chuan Park (probably the priciest en-bloc sale in 2022, at $890 million). Even then, the Chuan Park en-bloc has hit a road bump, with the STB issuing a stop order after three rounds of mediation.

And yet, notice the absence of big en-bloc announcements and enthusiastic foreign developer interest, for almost the entirety of 2022. This year, the cycle seems to be slow in restarting; and it leads us to wonder if we’ll see a break in the pattern.

The other question is whether that break will be a happy one for the property market.

Why are developers hesitant this year?

This is not a year like any other we’ve seen. Several factors are at play:

- A high-interest rate environment

- Rising ABSD and LBC

- Seller expectations in an undersupplied market

- Narrowing margins

1. A high-interest rate environment

Home loan rates are fast approaching 3.5 per cent, with three per cent being the current norm. This is a dramatic change from the period between 2009 to mid-2021 when it was plausible for home loan rates to fall below two per cent per annum.

A rise to three per cent or higher is psychologically significant: it’s higher than the HDB loan rate of 2.6 per cent, and higher than the risk-free CPF rate (to which the HDB loan rate is pegged. This is currently 2.5 per cent, and has been for over 20 years).

As one property investor said to us, she was no longer “borrowing for free,” referring to the years when the home loan rate was lower than her guaranteed CPF interest rate.

The rising interest rate has resulted in necessary changes to loan curbs; it is a bit tougher for buyers to qualify, and initial cash outlays will probably be higher. Developers need to weigh this factor, against the possibility of selling the entire development within five years (see below).

A particular worry is that HDB upgraders – who form the bulk of condo buyers – are priced out of new launches under the new loan restrictions, and developers with their thin margins (see point 4) are unable to price projects much lower.

More from Stacked

4 Reasons Why HDB Upgraders Prefer Executive Condos To Private Condos

Two common expressions you’ll hear in Singapore are “What? Why is an EC so expensive?” followed by “What? The EC…

After developers build, who is able to buy right now?

(To those who answer “wealthy foreigners”, we’d point out that foreign buyers have actually decreased since 2019, making up a mere 3.3 per cent of buyers in the first half of this year. And this demographic has seldom risen above a single-digit percentage even in previous years. Relying on foreign buyers works for developers building very niche luxury properties, and these don’t soak up significant market demand).

2. Rising ABSD and LBC

Developers now face 35 per cent ABSD, plus five per cent non-remissible. Developers need to build and sell every unit in the project within five years, to get ABSD remission.

In addition to this, the Land Betterment Charges (which have replaced Development Charges) are higher in most zones, leaving developers to either absorb higher costs or pass them down to increasingly struggling buyers.

One glaring issue here is that the ABSD is too unspecific: it’s applied regardless of whether the developer is building a 1,000+ unit mega-project, or a luxury landed project with just 20 units. Failure to complete and sell even a single unit means the developer must surrender the whole ABSD tax.

This incentivises developers to build small, rather than big – especially because of the current uncertain economic environment. This is a problem for the wider market, as small or boutique projects tend to mean a higher price point. Most small projects are marketed as being exclusive or highly private, part of integrated developments, in prime areas, etc. These projects soak up insignificant amounts of demand, as they house only a few affluent buyers.

A combination of high ABSD rates, and charges on developers, may be contributing to a tighter housing supply.

3. Seller expectations in an undersupplied market

Sellers can see prices rising to astronomical levels; it’s been going on since after the pandemic. For those who are landlords, they’re also seeing rental rates spike to record highs. Besides these, Singaporean homeowners are seemingly well capitalised; they can handle the spike in interest rates precisely due to the loan curbs enforced upon them.

Where then, is the incentive to sell low? En-bloc sellers will push for prices so high, that developers already saddled with ABSD, LBC, and other factors may decide against buying up larger plots. Most developers also prefer GLS sites, as en-bloc sites can come with complications (see Chuan Park), or even unforeseen construction issues that only come up after tearing down the existing site.

If developers are to rely purely on GLS sites (sites that are also not cheap, and viable only for the bigger developers), it explains why the housing supply is shrinking.

Another side-factor to consider:

The larger the project, the more dissenting voices will likely be present. 80 per cent consensus among the owners (by share value) is required for an en-bloc to proceed. This makes it tougher for bigger projects to go en-bloc, hence resulting in slower redevelopment of large land plots. This also drags down the available supply, albeit in an indirect and not precisely quantifiable manner.

4. Narrowing margins

Between ABSD, LBC, high seller expectations, a commission of up to five per cent* as a norm for sales teams, and a whole range of factors we describe here, developers are more squeezed than ever.

Given the land prices paid, for instance, it’s widely expected that the yet-to-launch Seneca Residence may be one of the last properties this year to fall below $2,000 psf; but even at this pricing, buyers from earlier decades will probably be shocked at the cost of such a non-central project. But it’s not as if developers have much room to drop prices further.

Developers are now in a precarious situation, where they need to decide if there are sufficient buyers over five years, for the rates they have to charge.

What if the en-bloc cycle is broken?

If there’s no interest in en-bloc sales, then GLS sites alone are unlikely to provide an abundance of land (unless the Government does open up the supply). We may see supply continue to hover at the current range, and this is to the detriment of buyers in general – scarcity means private homes will be increasingly out of reach for the majority.

Most sellers benefit from this, but it’s not a universal upside for them either. Those who counted on en-bloc sales as an exit strategy, for instance, may need to shelve their hopes for the time being. This is an unusual outcome, for those who sought to time the five-year cycle of redevelopment.

There are also other movements to consider, like HDB increasing the BTO supply (23,000 flats per year). This could take away the demand from the resale HDB market, which should put a dampener on increasing prices. This in turn would affect HDB upgraders as well – and affect demand for mass-market condos.

This being said, we could all be wrong, and perhaps the resurgence in en-bloc sales is just delayed due to the current economic uncertainty. Perhaps all the en-bloc announcements will be back in full force later in 2023, once the market has adapted to the various changes. But for now, things are disturbingly quiet on this front.

For more updates on the situation, follow us on Stacked. We’ll also provide you with in-depth reviews of new and resale properties alike.

If you’d like to get in touch for a more in-depth consultation, you can do so here.

Ryan J

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Read next from Singapore Property News

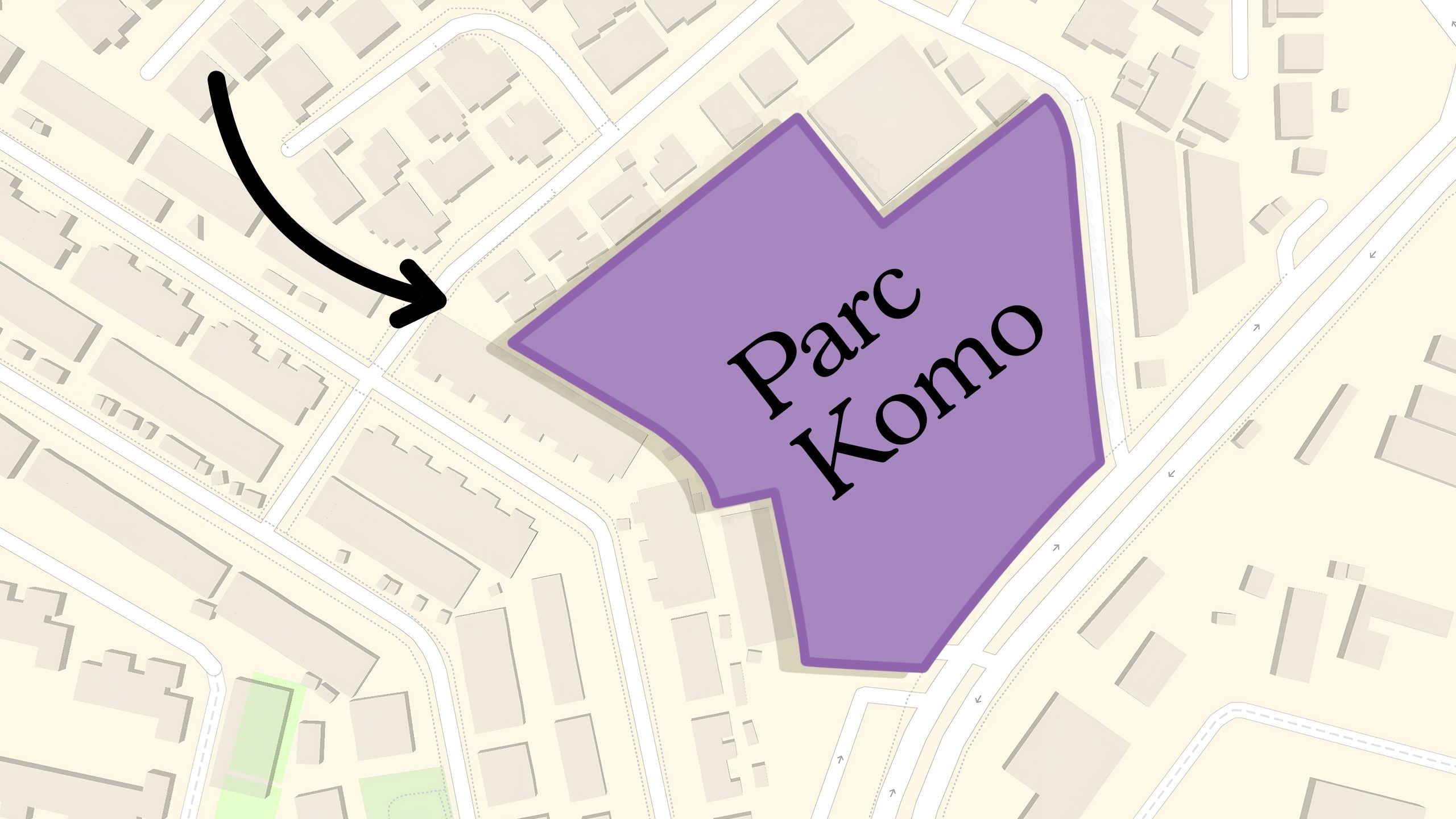

Singapore Property News 10 New Upcoming Housing Sites Set for 2026 That Homebuyers Should Keep an Eye On

Singapore Property News Will Relaxing En-Bloc Rules Really Improve the Prospects of Older Condos in Singapore?

Singapore Property News A Housing Issue That Slips Under the Radar in a Super-Aged Singapore: Here’s What Needs Attention

Singapore Property News This 5 Room Clementi Flat Just Hit a Record $1.488M — Here’s What the Sellers Took Home

Latest Posts

Property Investment Insights Why This Freehold Mixed-Use Condo in the East Is Underperforming the Market

Homeowner Stories I Gave My Parents My Condo and Moved Into Their HDB — Here’s Why It Made Sense.

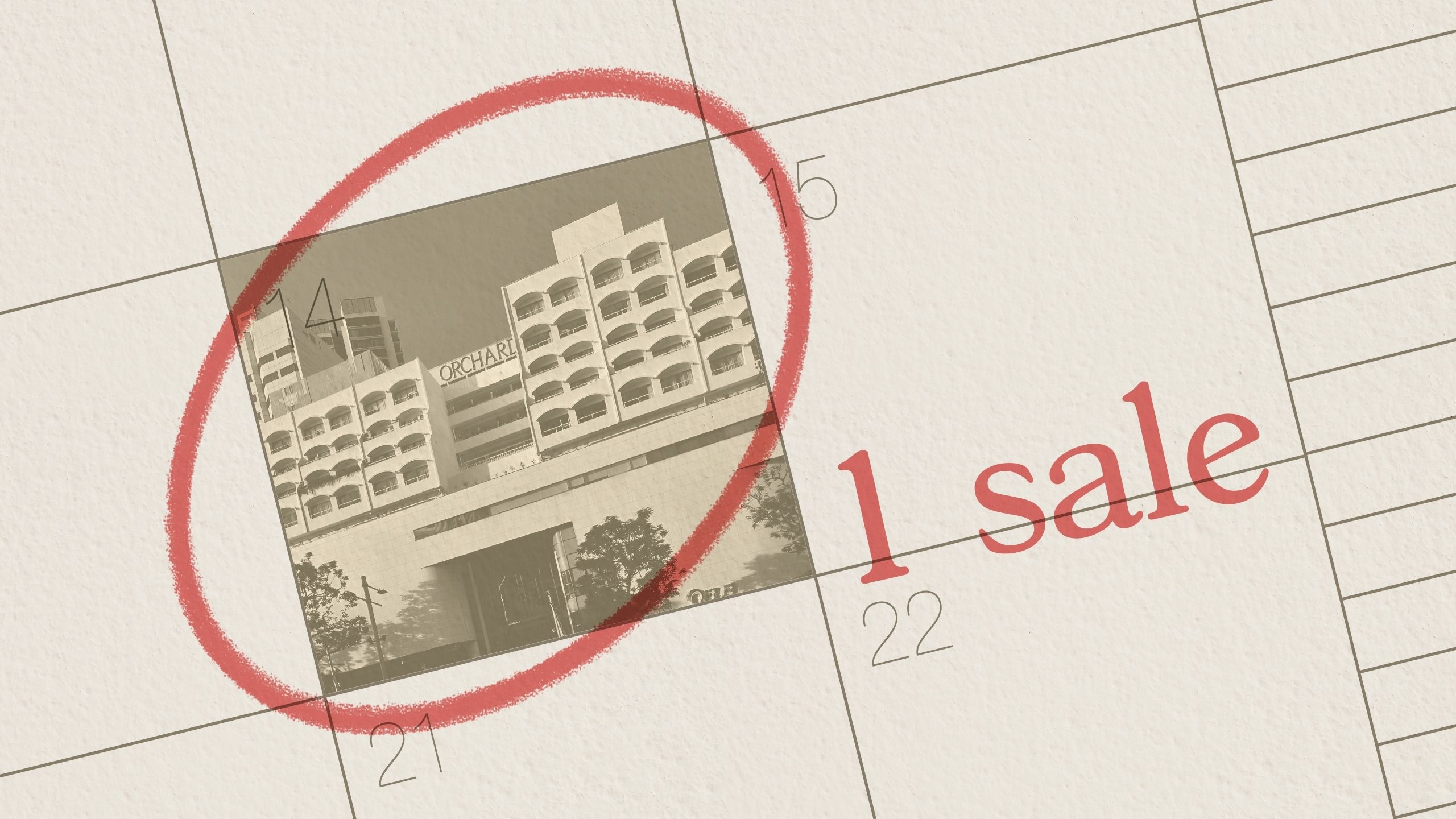

Property Market Commentary The Rare Condos With Almost Zero Sales for 10 Years In Singapore: What Does It Mean for Buyers?

Property Investment Insights Why This Large-Unit Condo in the Jervois Enclave Isn’t Keeping Up With the Market

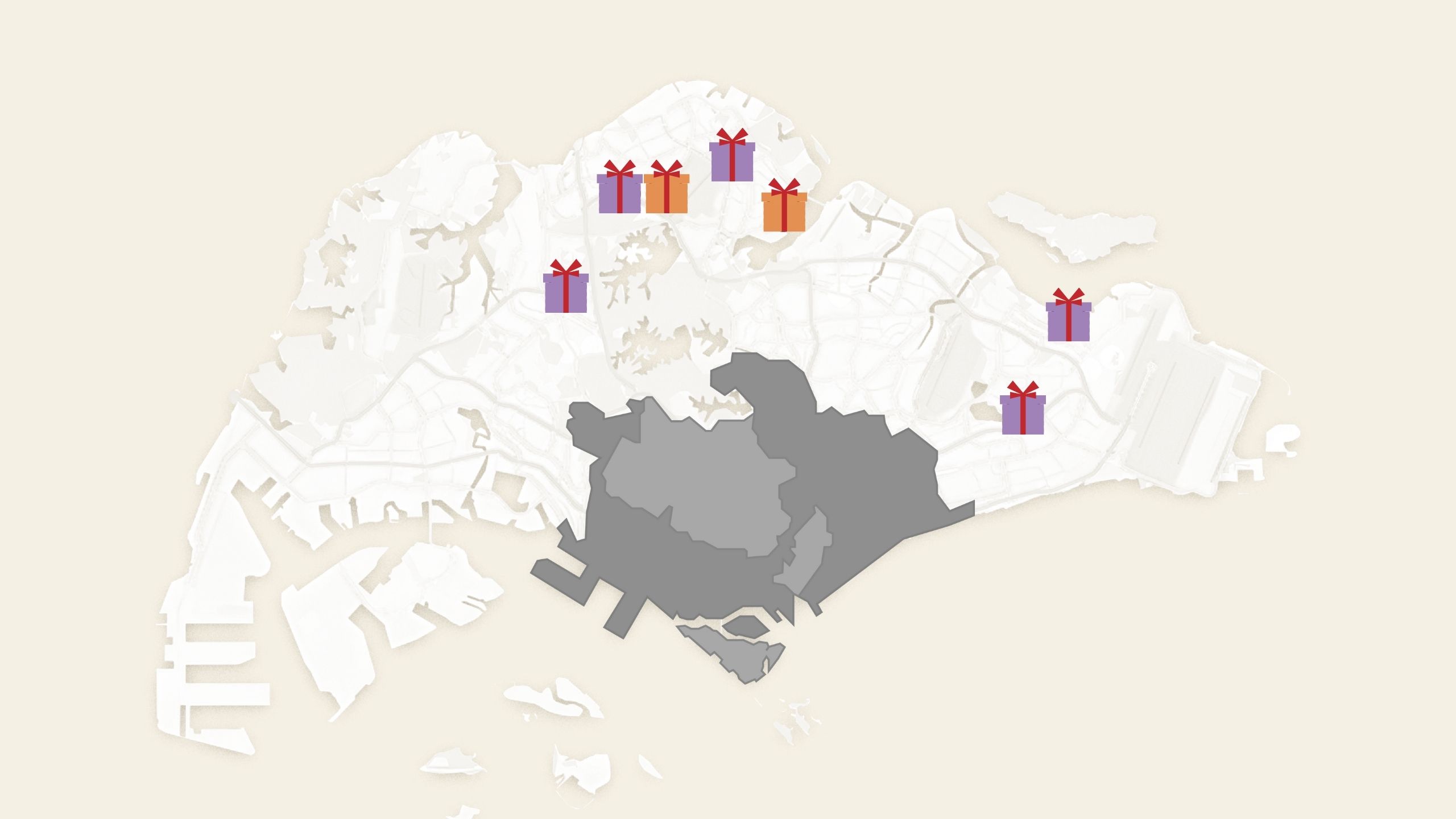

Property Market Commentary 5 Upcoming Executive Condo Sites in 2026: Which Holds the Most Promise for Buyers?

Landed Home Tours Inside One of Orchard’s Rarest Freehold Enclaves: Conserved Homes You Can Still Buy From $6.8M

Property Investment Insights These 5 Condos In Singapore Sold Out Fast in 2018 — But Which Ones Really Rewarded Buyers?

On The Market We Found The Cheapest 4-Bedroom Condos You Can Still Buy from $2.28M

Pro Why This New Condo in a Freehold-Dominated Enclave Is Lagging Behind

Homeowner Stories “I Thought I Could Wait for a Better New Launch Condo” How One Buyer’s Fear Ended Up Costing Him $358K

Editor's Pick This New Pasir Ris EC Starts From $1.438M For A 3-Bedder: Here’s What You Should Know

Pro Why This Mixed-Use Condo at Dairy Farm Is Lagging Behind the Market

Property Market Commentary We Analysed Dual-Key Condo Units Across 2, 3 and 4 Bedders — And One Clear Pattern Emerged

Editor's Pick How This Singapore Property Investor Went From Just One Property to Investing in Warehouses and UK Student Housing

Editor's Pick We Toured A Quiet Landed Area In Central Singapore Where Terraces Have Sold Below $8 Million