Why Early Buyers In New Housing Estates May See Less Upside In 2026

February 2, 2026

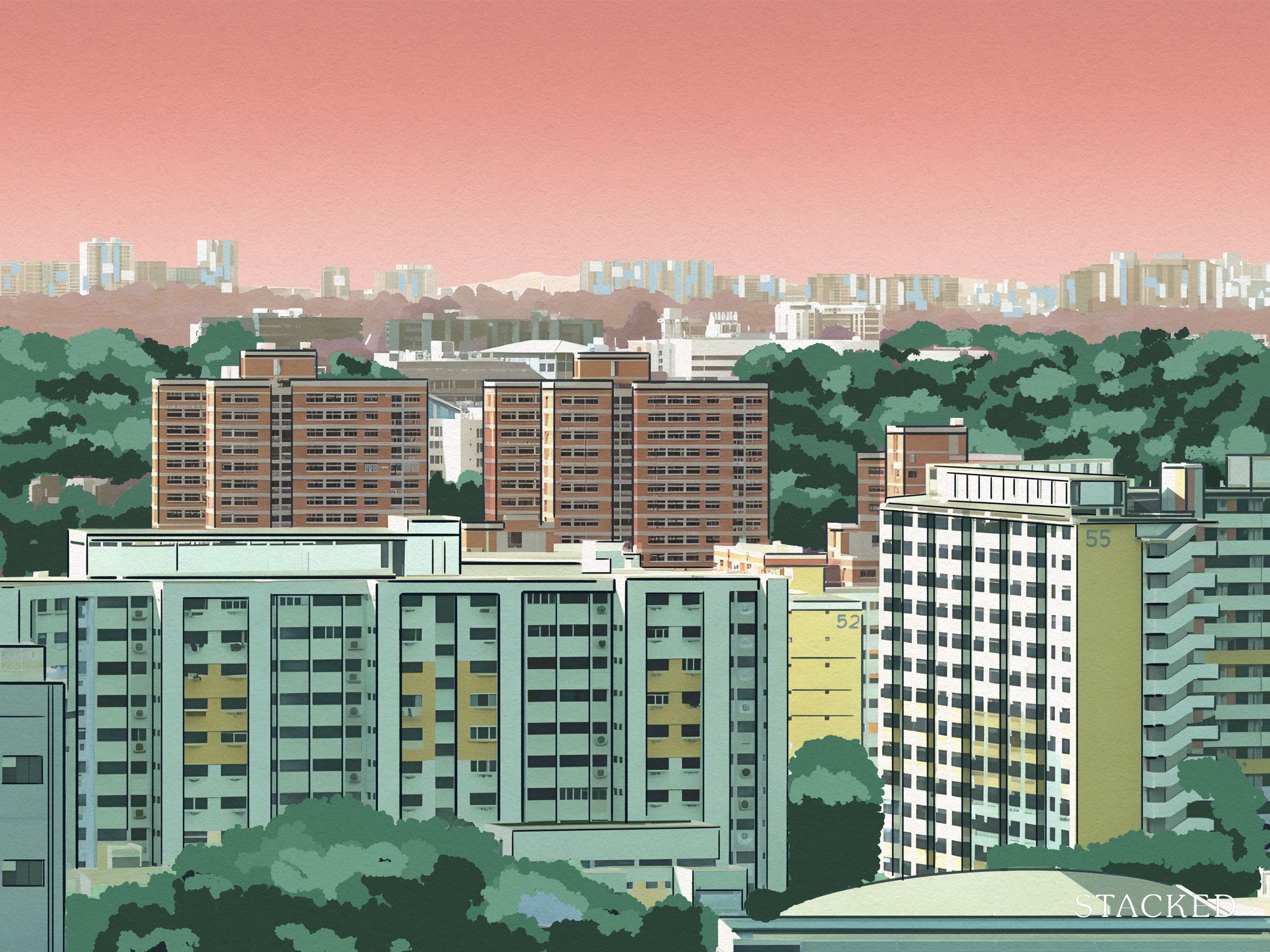

In the early 2000s, buying a home in locales like Punggol or Woodlands was considered a compromise. In less generous terms, some even called it desperate since back then those “ulu” areas often meant long commutes and sparse amenities. It was also not uncommon for realtors to advise buyers to avoid these areas if possible, claiming that they would never appreciate fast enough to bridge the gap if they intended to eventually upgrade to a private property.

But looking at the real estate landscape of these two locales today, it’s clear that most of those realtors were wrong and these areas have improved so much so as to be nearly unrecognisable today.

Even the most “ulu” estates, which we might colloquially call today, often boast at least small malls or MRT connections (or at the very least, LRT connections). Many also have employment nodes factored into the town’s development, such as the Punggol Digital District, or Jurong East’s transformation into our “second CBD.” And with these vast improvements, some early buyers have been rewarded several times over for their patience.

The question is whether the kind of first-mover advantage those early buyers managed to capitalise on can continue to exist, in Singapore’s urban landscape that’s now much more connected via public transport networks and increasingly decentralised.

Many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

What a first-mover advantage used to mean.

By first-mover advantage, I don’t refer to speculation or planning; not everyone who benefited from it actually had the intent to do so.

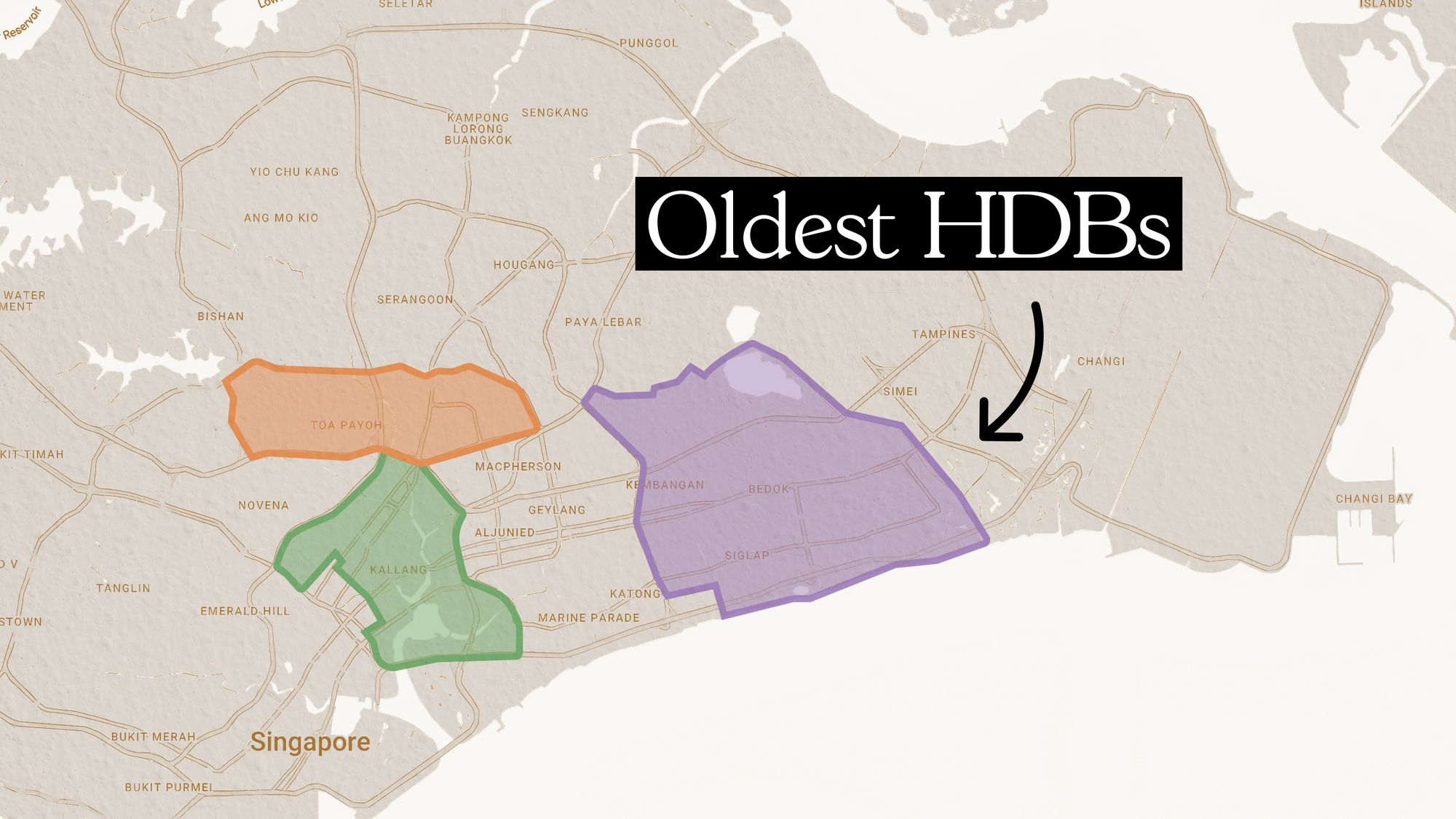

Historically, first-mover advantage in our local property market context – especially in non-mature HDB towns (back when we still used this definition) often meant buying before convenience, at a lower price. This dynamic was clearest in HDB towns like Punggol or Woodlands, where it was expected that commutes would be a chore.

While there was often news that future MRT lines an dmore regional centre amenities were in the works, it was still likely that many buyers bought there due to the relatively affordability of homes there. Getting the first-mover advantage wasn’t so much a form of ingenious property investment as it was about just having a home.

The payoff for that, however, has been huge.

It’s also often overlooked. Media headlines like to highlight the windfall of those who secured flats in central areas like Bidadari, but we often overlook the progress of the formerly “ulu” towns.

For example, in our analysis of HDB towns with the most resale activity in 2025, four-room flats in Punggol were transacting at an average of $684,052. For comparison, prices were within the low-$400,000 range back in 2015, which we covered in this much earlier article.

Granted, a part of this price surge was due to the post Covid-19 pandemic recovery period between 2020 and 2023, but we can see prices were rising consistently even before this volatile period.

The phased development of the Punggol Digital District (PDD) has also been a significant contributor to the growth of the Punggol estate in recent years. The first wave of commercial tenants at PDD began moving in last year. The development of the PDD goes beyond a rejuvenation project like improving transport links; in some cases, it could remove the need to commute altogether, as institutions and businesses move into the new business and commercial hub.

Another notable example is Woodlands.

It was once considered the very definition of “ulu” among some Singaporeans, but resale four-room flats in Woodlands recorded an average price of $565,614 in 2025. About a decade ago, prices were also in the low $400,000 range, similar to Punggol. Price growth in Woodlands is likely to increase further as the region progressively transforms into a new regional hub and the Johor Bahru-Singapore Rapid Transit system (RTS) is completed at the end of this year.

You’ll notice I’m using four-room flats in these examples, as these tend to be the most ubiquitous family-sized HDB homes in Singapore. The point is that most of these units were not bought by investor-minded buyers who foresaw the coming transformations. In many cases, these locations were chosen by average families because they were among some of the most affordable options available to them at the time.

But is this still a continuing possibility, going forward?

The conditions in the property market that enabled some to enjoy a first-mover advantage in prior HDB eras may no longer exist in quite the same way.

In the past, towns were often developed in stages. Homes typically came first with some amenities, but the bulk of the commercial and retail offerings tended to follow later. MRT stations, heartland amenities, and employment opportunities gradually stabilised and grew as the town matured; at times, many years after residents had already moved in.

This development period allowed for significant price appreciation as neighbourhoods saw equally significant upgrades. But today, the difference in urban development and estate maturity between HDB towns in Singapore is far less evident.

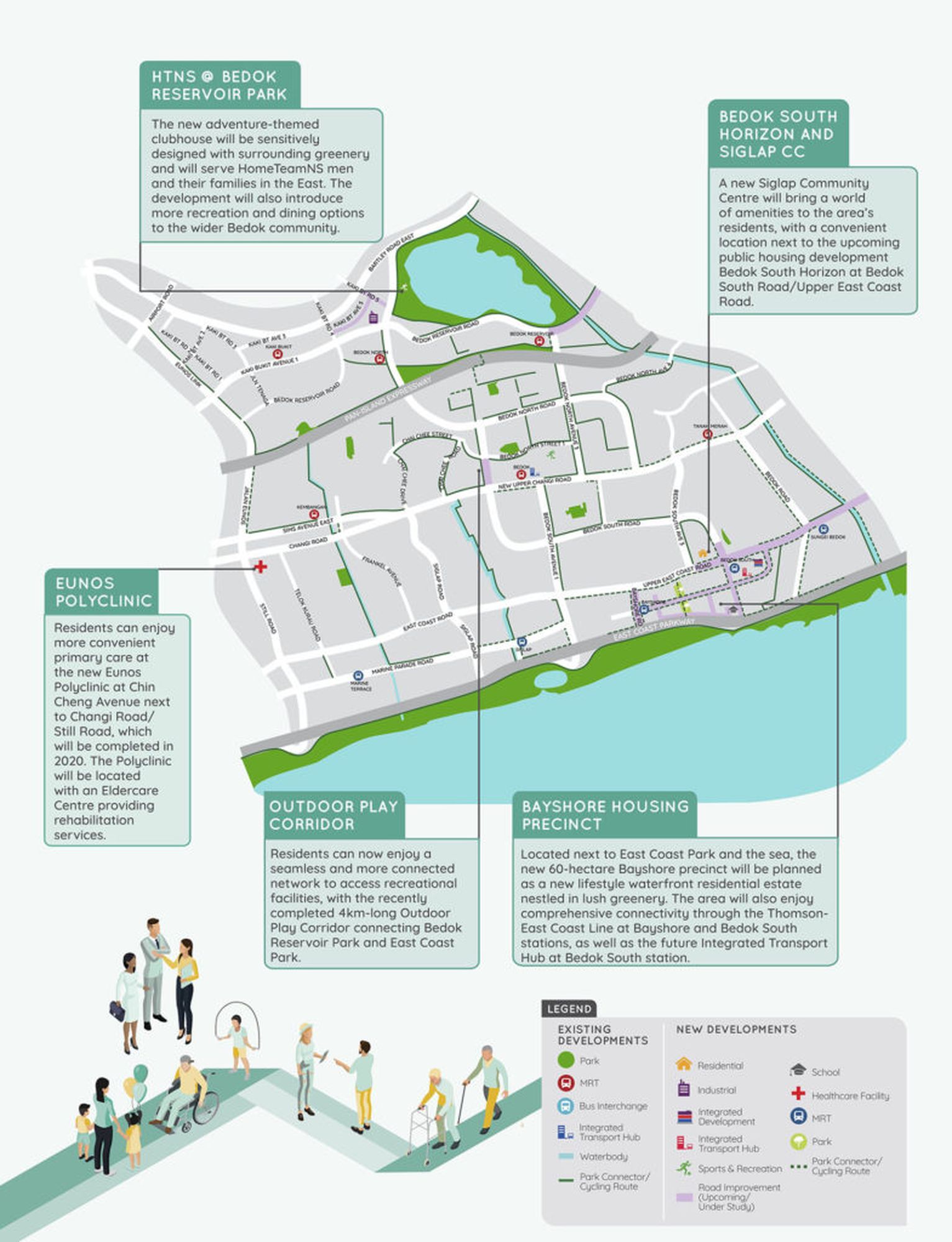

New towns and precincts are launched with transport connectivity and amenities already outlined during the master planning phase. A clear example of this is the upcoming Bayshore estate: chances are, before 2020, most people would never have heard of Bayshore. If they did, they likely just thought of it as an ulu area with three big condos.

More from Stacked

Does The “Sell One, Buy Two” Strategy Still Work In 2025? 3 Real Stories From Singapore Homeowners

After the government imposed the Additional Buyers Stamp Duty (ABSD) in 2011, a popular strategy for a time was the…

The plans to launch an HDB estate in Bayshore, however, are ambitious. From the very start, most of the upcoming flats fit the criteria to be designated as ‘Plus’ projects. The Bayshore MRT station (TEL) is already built, and a local mall is already planned. All of this happened before households moved into their new homes.

As an aside, we see some examples of buyers pricing in the potential future price upside in some developments. Vela Bay – has already set a record for an Outside of Central Region (OCR) land price of $1,388 psf.

If this sets the precedent for future new towns and estates – as it likely will – then buyers are no longer moving in ahead of infrastructure. Rather, they’re moving in alongside it, or even after elements of it are already in place.

If you want a less ‘premium’ example – something that’s not a Plus project – let’s consider the HDB projects in Tampines North.

This is close to the cluster of retail big-box buildings like IKEA, Giant, and Courts near Tampines Avenue 10. Certainly an area that’s not as developed as the central hub of Tampines. But is the “ulu” factor as extreme as what Punggol, Woodlands, or perhaps Jurong East experienced in the early days of their township?

I would question that, and not only because the area has a relatively quick, direct bus connection to the centre of Tampines (which has three malls, grade A office spaces, and is the regional centre of the east). Park Town Residences, an integrated project here, will be completed by 2030; it’s connected to the upcoming Tampines North MRT station (CRL), introduces a preschool, and has a CapitaLand-run mall component.

Perhaps another telling sign is that, despite the area’s supposedly “ulu” status, Parktown sold 87% of its 1,193 units over its launch weekend, and at the not-insignificant price of $2,360 psf for this fringe-area condo.

(While Parktown is a private project, my point about the $PSF is how future infrastructure is already being priced in.)

The reality is that residents here are not isolated from amenities in the way earlier generations of buyers were. I’m not saying there’s no inconvenience compared to more mature towns, but the degree of it is significantly diminished.

The old ‘first-mover’ discomfort has shifted from uncertainty to merely expectation.

Lately, most buyers plan their property purchases with greater visibility of upcoming MRT stations or along lines that are already operating, even in new towns. The upcoming malls planned for the area are likely earmarked in the area’smaster plan, and future employment nodes may already be named, as is the case with the PDD and Woodlands North Coast.

This is a different approach compared to previous eras, where buyers didn’t usually know what to expect in future; at least not so clearly. An upcoming new estate like Bayshore or Tampines North is a like-for-like comparison to early Punggol or early Jurong East because homebuyers have a better appreciation of the master plans for the area.

On the downside, this could have implications for price appreciation.

We still expect HDB to keep public housing prices affordable, and the government has shared its aim of pricing future BTO flats with this affordability in mind. But once projects hit the resale market, pricing expectations can climb significantly.

In the past, resale prices in “ulu” areas tended to rise more slowly because the area’s inconvenience acted to dampen price growth, and there was a relatively longer development period. The resale market more or less demanded a discount until amenities and accessibility materialised.

Today, with decentralisation and urban master plans, the perceived “discount window” is shorter. The future of a town, even a brand-new one, is already visible and well-documented. As a result, the scope for dramatic buy-low-sell-high outcomes is concentrated among the initial batch of BTO buyers. For subsequent buyers, price appreciation is more likely to be steadier and more incremental, rather than driven by the sharp jumps from the past.

On the upside, this is a win for genuine homebuyers, who are less focused on resale gains.

For true owner-occupiers, any inconvenience must be temporary and resolvable. Buying into a less mature area today may not mean the same degree of gains as in previous eras, but for a housing system that’s meant to prioritise a roof over your head, that’s exactly how it should be.

It just means that in the future, the first-mover advantage will play out more gradually. Gains are less likely to be explosive and more distributed over longer periods, while prices may adjust earlier. Overall, this is arguably a win for the average Singaporean homeowner.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

Will early buyers in new estates still see big price gains?

How has the development of new towns changed in Singapore?

Are prices in 'ulu' areas like Punggol and Woodlands still rising fast?

Does the improved connectivity mean less chance for quick property gains?

Is buying in a new estate still a good idea for owner-occupiers?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News Why Some Singaporean Parents Are Considering Selling Their Flats — For Their Children’s Sake

Pro River Modern Starts From $1.548M For A Two-Bedder — How Its Pricing Compares In River Valley

New Launch Condo Reviews River Modern Condo Review: A River-facing New Launch with Direct Access to Great World MRT Station

0 Comments