Why It’s So Much Harder For Young Singaporeans To Buy A Home Today

December 10, 2025

There’s a predictable reaction to younger Singaporeans who hear about home prices for the first time, especially those who aspire toward home ownership. It’s eyes like flying saucers, and a jaw that they have to pick up off the ground. It’s not just the price tag – although that’s a big part of it – it’s also about the tight restrictions on financing. From being self-employed to needing a down payment they can barely conceive of, the common question is why. And the truth is, it’s not their fault that earlier home ownership is tougher on them than on their parents. If you’re part of that generation, here’s an explanation of how we got to this point:

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

1. The scars of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) are still affecting you today

In around 2008, the GFC sent global markets into chaos. There was a negative impact on property prices as well, initially – in Q3 2008, the URA Housing index dipped around 2.4 per cent, but then plummeted around eight per cent over the next six months.

However, this meant Singapore property was cheap – and many investors saw it as a safer option than the conventional stock and bond markets. So they rushed to buy and, by 2013, property prices had reached a whole new peak.

The reason wasn’t just that property was cheap, but also because of many things you could do in the past that you can’t get away with now. You could:

- Borrow up to 90 per cent of your property value

- Take crazy long loan tenures; many stretched out their home loan to 35 years, and even 40 years was possible; at one point, UOB was offering a 50-year mortgage

- You could flip properties very easily. You didn’t even have to buy the property – some people even put down the money for the Option To Purchase (OTP), and then transferred the OTP to someone else for a profit.

- You could decouple an HDB flat. So you could transfer your share of your flat to your spouse, and then buy a private property under your own name.

And yes, that would also avoid ABSD, which was introduced in 2011; but ABSD in those days wasn’t a big deal anyway – it was only three per cent, and would only be applied on your third property if you were a Singaporean or PR.

By around 2013, a huge property bubble was forming; so the government started implementing crackdowns in the form of cooling measures. These measures were called temporary, but over the years, we’ve never seen them go away. Instead, they’ve only intensified.

As some examples: Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) was introduced, which capped your total debt (including car loans, credit cards, etc.) to 60 per cent of your income (today it’s even lower at 55 per cent.). For HDB loans, the Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR) capped housing costs to 30 per cent of your income, and HDB loan tenures were cut from 30 years to 25.

All of these helped to cool the market and weakened the property market right up till around 2017 – more on this below. But suffice it to say that many of the obstacles you run into today were put there in an attempt to slow housing prices.

It’s just an unfortunate twist that, whilst exerting downward pressure on prices, they simultaneously make it harder for you to buy.

2. We actually did have resale flat prices under control, but COVID wrecked that; and you’re the generation facing the fallout

Resale flat prices have gone up quite a bit; and even if we want to argue that they’re still affordable, we can’t say they haven’t gotten less affordable. If you’re wondering how things got to this state, well…the government did try to do something about it.

Back in January 2013, when property prices were crazy high, two big moves were brought in to cool resale flat prices. The first was the Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR): This capped how much of your income could go toward repaying your home loan, set at 30 per cent (e.g., if you make $4,500 a month, your maximum home loan repayment is $1,350 per month.

Overnight, many buyers couldn’t borrow as much as before, which limited how much they could pay for resale flats. This, in turn, caused sellers to lower their asking prices.

Second, HDB stopped publishing Cash Over Valuation (COV) numbers. COV is the amount you need to pay on top of your flat’s actual valuation – so if the flat is valued at $700,000 but the seller wants $750,000, then the COV is $50,000.

This used to be a very expected thing: buyers and sellers would know the valuation, and then negotiate the COV separately. So what HDB did was to simply stop showing the COV data. You now have to agree on the price with the seller, before HDB will show the actual valuation, and that prompts buyers to make more cautious offers.

This actually worked really well.

Resale flat prices fell for 13 straight quarters from mid-2013 to 2017, ending up more than 10 per cent below the peak. In fact, just one year after the new measures, COV began to average $0. Sometimes you could even find flats transacting at negative COV, something that – in 2025 – is about as realistic as a whole herd of unicorns.

And if nothing had changed, affordability would look much better today. Resale flat prices did start to stabilise again toward 2018/19, but they were still sane: a 3-room flat in a place like Hougang, at the time, could possibly be below $300,000.

But then came COVID-19. Construction delays, supply bottlenecks, and a sudden spike in demand for bigger homes (WFH, young families wanting space sooner) turned everything upside down. With fewer new flats being completed and fewer condos on the market, attention shifted back to resale.

From 2020 to 2022, resale flat prices jumped almost 28 per cent. In just those 10 quarters, we undid several years of falling prices – and HDB resale flat prices have now soared past even the 2013 peak.

So it’s not that you feel you’re paying more than Gen X or the Millennials – you are paying more, as the Millennials at least had a shot between 2013 to around 2018/19.

3. You’re more likely to be self-employed or in the gig economy, which makes financing tougher

The younger you are (and you’re the youngest generation entering the housing market, now or soon), the more likely you are to be self-employed or a gig economy worker. This was as true for later Millennials as it is for you.

Here’s the thing: when we talked about the TDSR and MSR above, those limitations are for salaried employees. For self-employed or gig-economy workers, your income is considered 30 per cent lower for calculating those limitations. So even if you earn $6,000 a month, you count as earning $4,200 per month. And that puts your TDSR limit at $2,310 per month, making it hard to even buy a compact condo unit.

(For MSR, the “haircut” on your income varies based on HDB’s assessment, but for TDSR, banks will always apply a 30 per cent haircut.)

None of this was intended to make home buying tougher for you; it was to ensure buyers didn’t over-leverage. But again, you just happen to be more likely affected than previous generations, where salaried employment is the norm.

More from Stacked

Sell your home: 5 actionable tips to take for a first-time home seller

"Sell your home Singapore" will probably be a trending search term on Google next year, as home prices are set…

4. Just about every generation has had to deal with smaller and smaller homes, but here’s why yours seem especially tiny

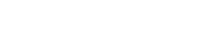

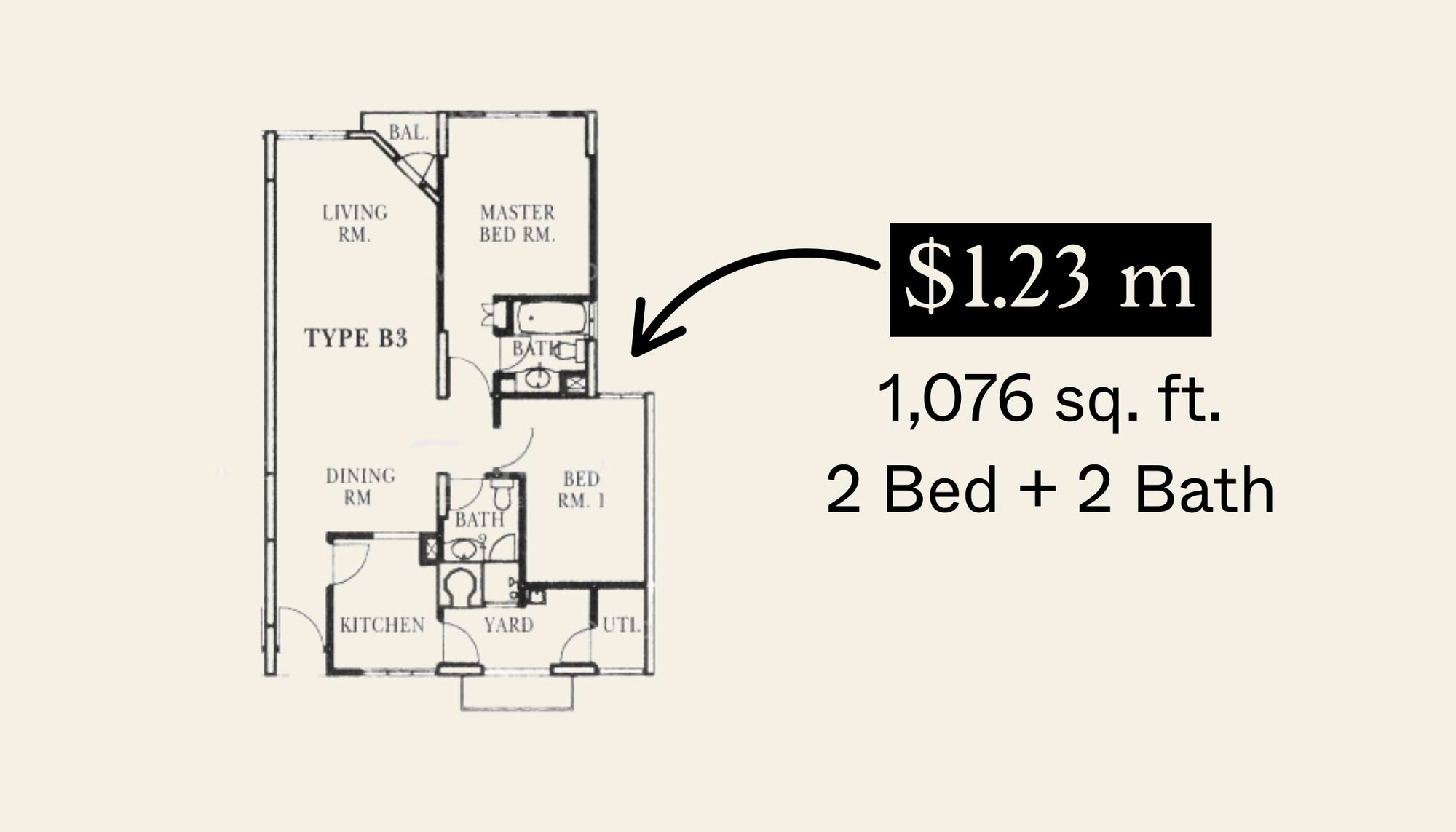

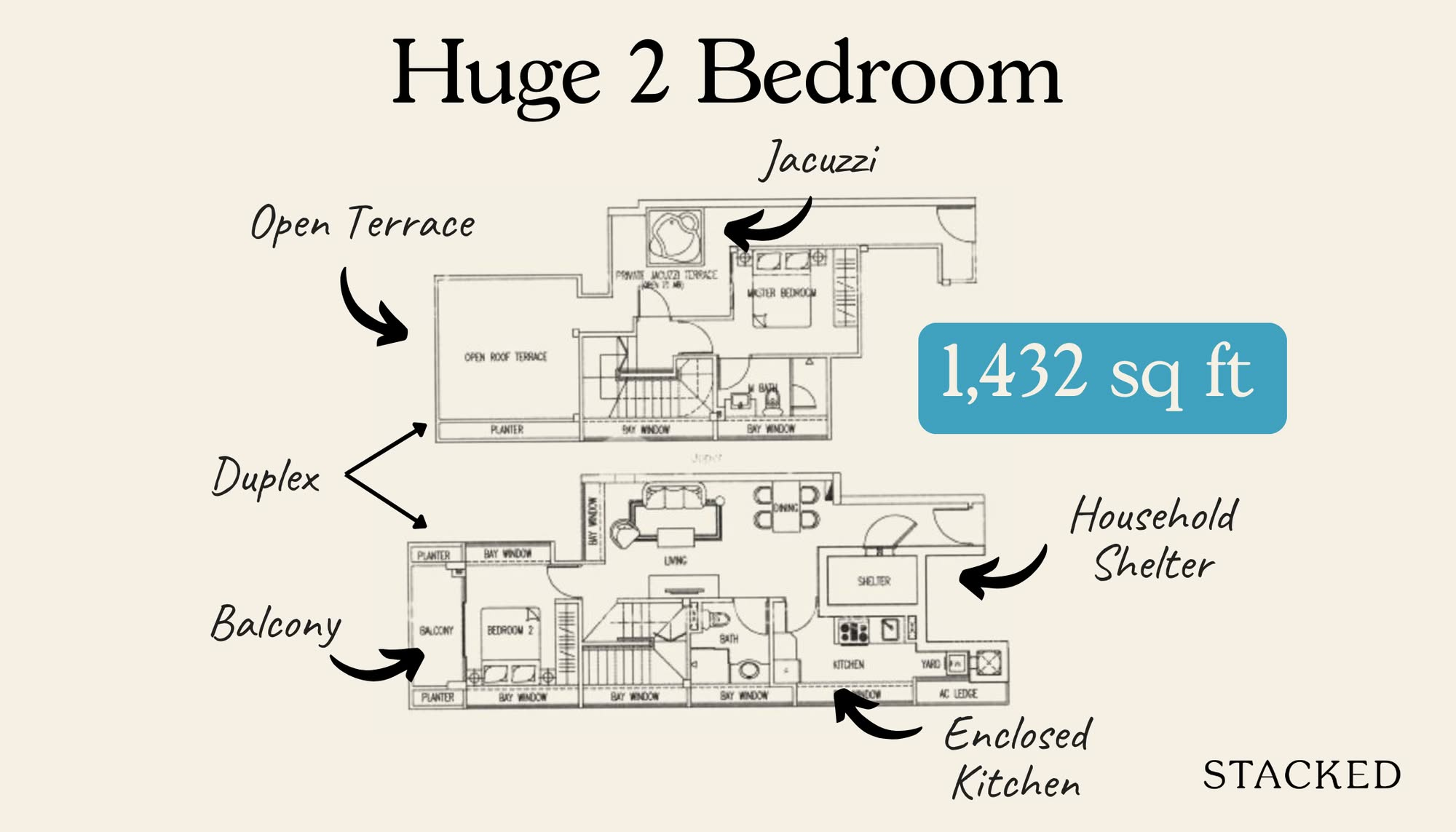

Let’s start with the condo market. Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, developers had far fewer constraints on unit sizes.

It was common to see three-bedroom condos measuring 1,200 to 1,400 sq ft, while even the “starter” one-bedders often came in at 600 to 700 sq ft. Families could expect a proper kitchen, a utility yard, and sometimes even a storeroom.

That all began to change in the 2010s. The first culprit was shoebox units: it became trendy to purchase a one-bedder shoebox unit to rent out, and a second, larger unit to live in. This was the era of the “shoebox craze.”

To prevent all our homes from becoming hamster cages, URA stepped in with minimum average size rules in 2012 (originally 70 sq m, later raised to 85 sq m in outside-central areas) to curb the flood of micro-units.

At the same time, plot ratio limits weren’t rising much, so the only way to squeeze in more saleable units was to cut down on size.

The shoebox craze ended roughly around 2017. However, condo sizes in that era were…still kind of a lie. We saw numerous inefficiencies used to pad the square footage, Developers leaned into bay windows, planter boxes, and the infamous oversized air-con ledges. On paper, the unit looked bigger, and the developer could charge you more. But in practice, the space could be useless, because several hundred square feet were ledges to mount compressors (or in some cases, void space, which is the area between the floor and ceiling).

By the 2020s, the new GFA harmonisation rules (2023) fixed this. Developers could no longer “game” the system by excluding bay windows, planter boxes, or air-con ledges from the floor area. But when you shave these off, the units also appear a lot smaller on paper.

That’s not so bad, as it’s just a theoretical loss of space

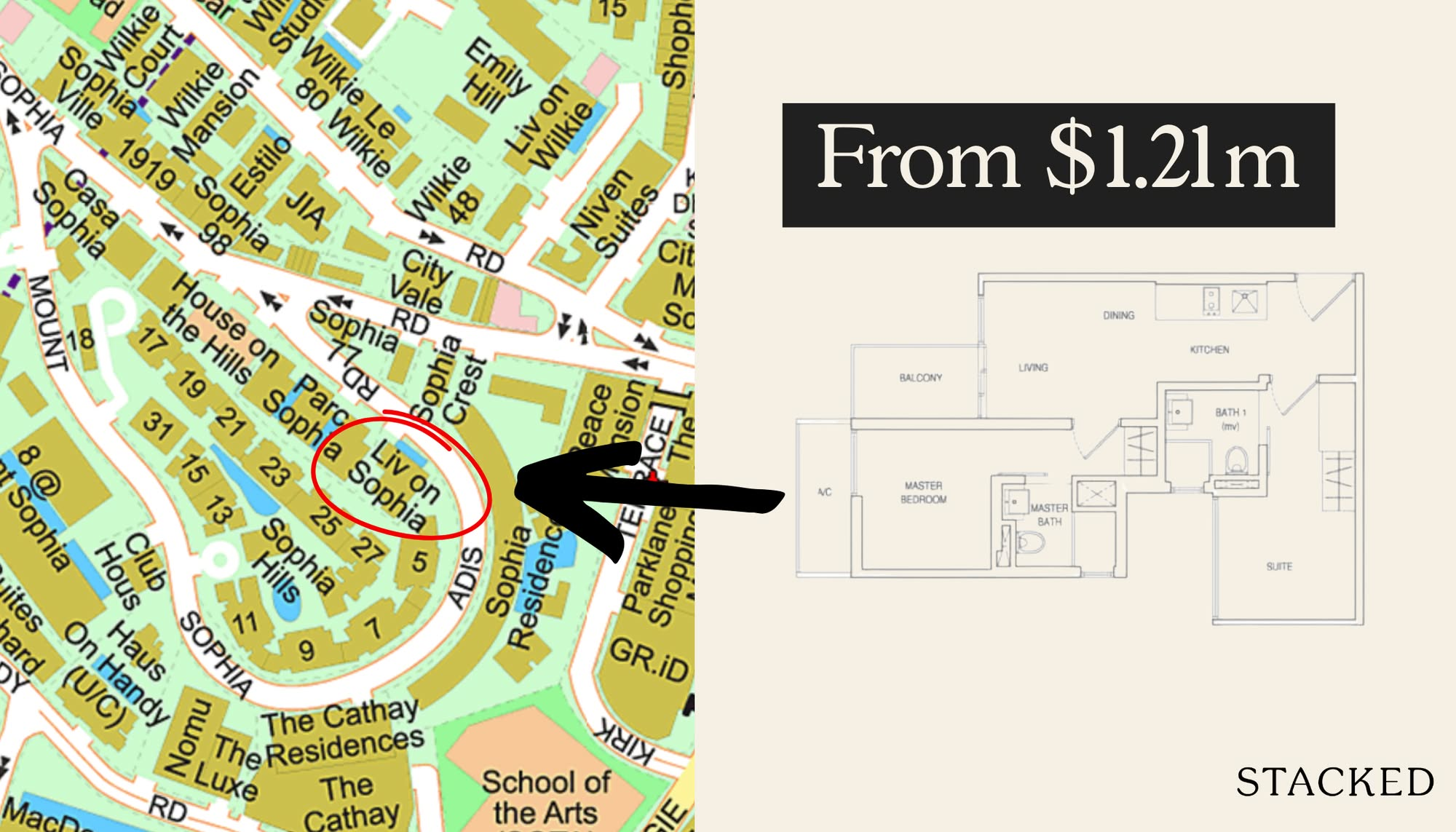

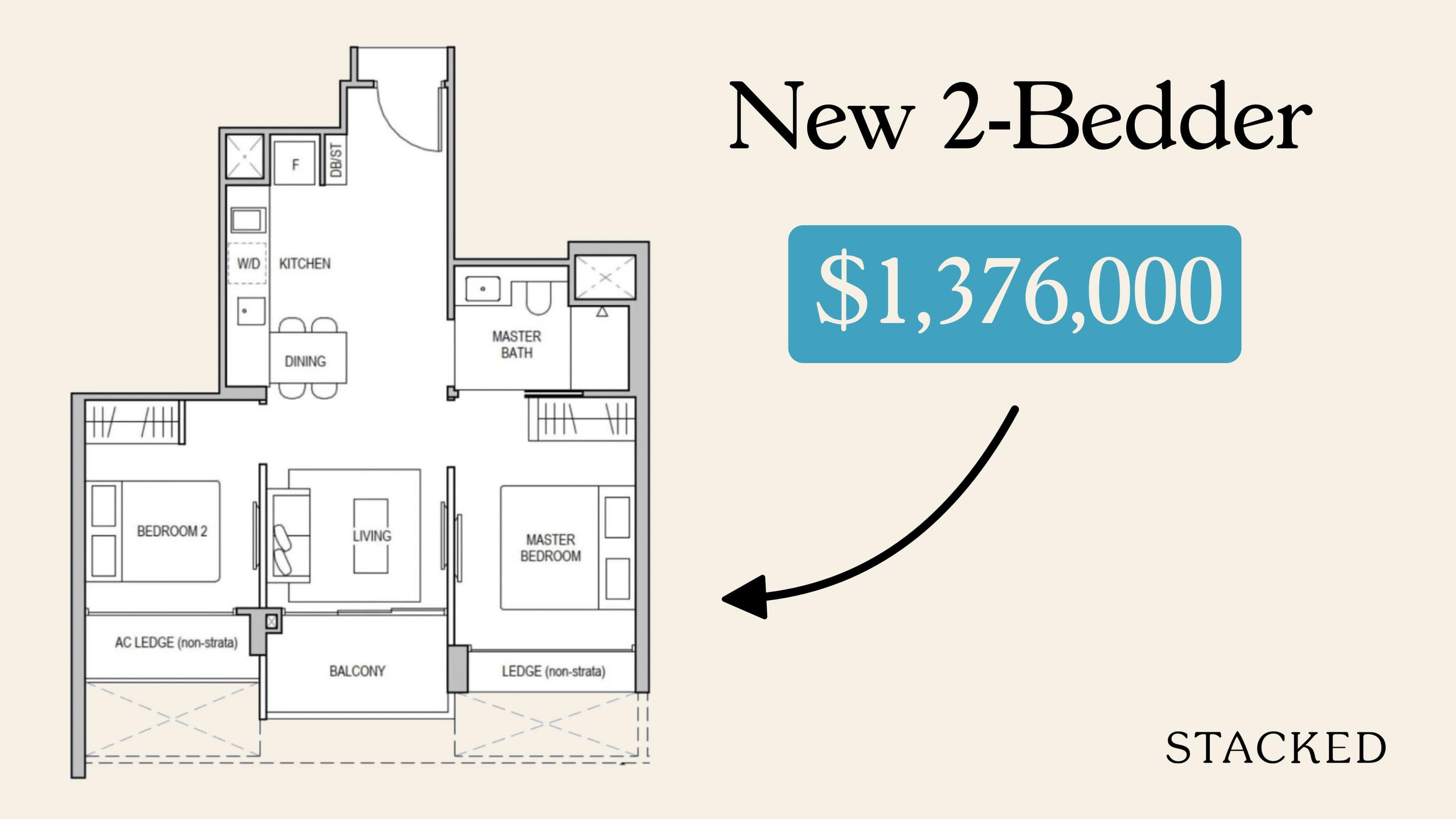

But today, condos like River Green show a new trend: developers – and even buyers – are less focused on price per square foot, but on overall pricing. At $3,100+ psf, it looks steep, but buyers weren’t scared off – because the overall price (the quantum) for a compact one-bedder still starts from around $1.2 million.

The psychology has changed: buyers today know they can’t control psf, but they can stretch for a sum that meets, say, TDSR limitations.

This is why new three-bedders hover around 800 to 900 sq ft, (around 700 sq ft for compact ones like a 2+Study), and one-bedders can slip under 500 sq ft. Developers shrink the units, keep the entry quantum “palatable,” and rely in more efficient use of space (whether or not that last part’s true is going to be up to you.)

For your parents’ generation, the conversation was: “What’s the psf? How much bigger can I get for the same money?”

For your generation, it’s: “What’s the overall price, and can I afford the monthly repayments?”

You’re living in a whole different housing market, because very large homes are likely unaffordable to you; unless you’re happy to buy a very old condo or a walk-up apartment.

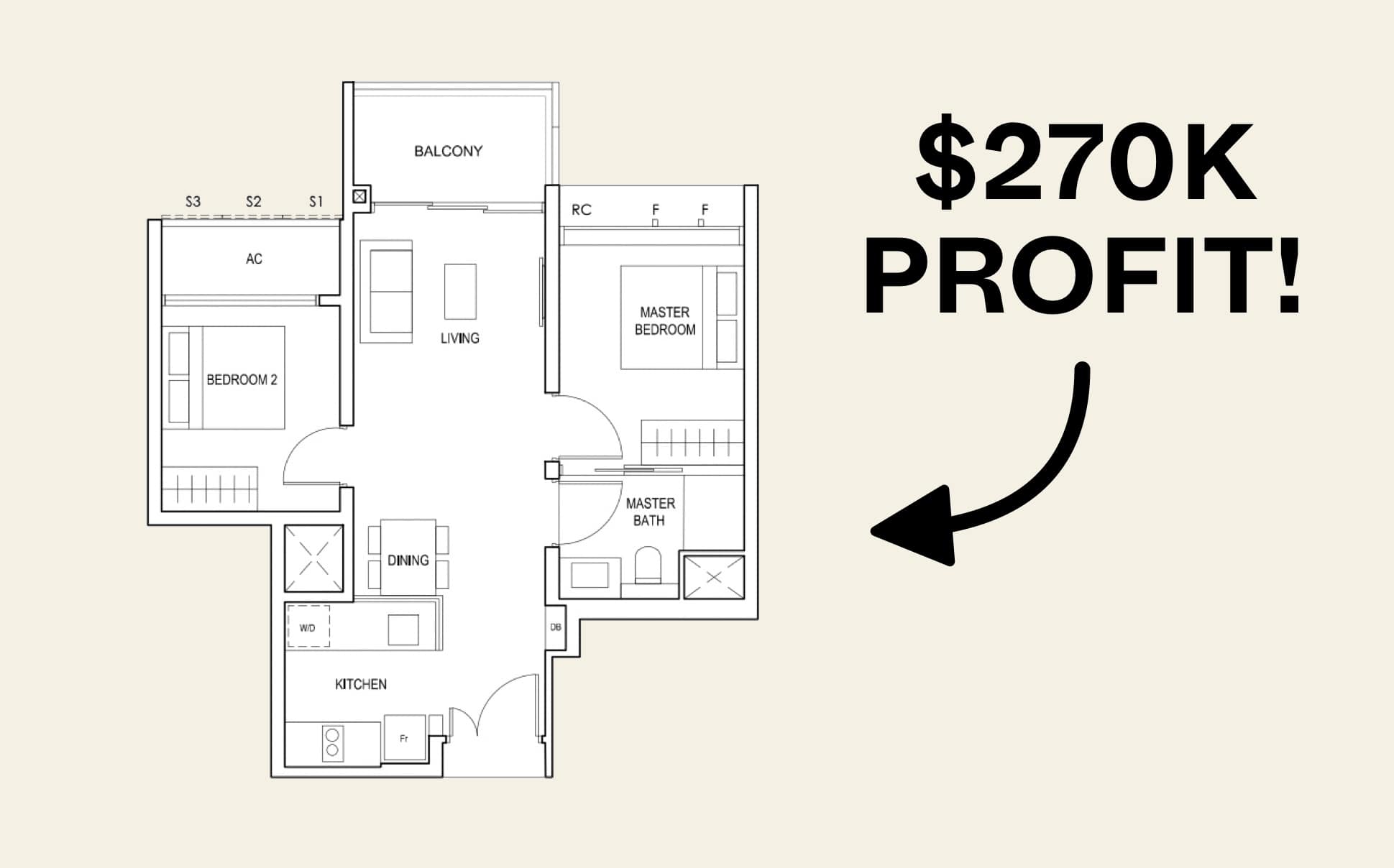

5. We ended the “HDB lottery” to make things fairer for you…but that also meant you never got a shot at a lottery ticket

There was a time when buying an HDB flat wasn’t just about finding a home. It was like buying a lottery ticket. If you balloted for the right project, in the right location, you could make a six-figure windfall after your Minimum Occupation Period (MOP).

Pinnacle@Duxton, Dawson, or even the early launches in Queenstown and Toa Payoh turned some ordinary Singaporeans into “lottery winners” overnight. This was the windfall effect of securing a flat in a high-demand area; the last known instance was Bidadari is also a good example of this: a BTO launch in 2015, even 3-room flats here have resold for about $900,000.

There was a lot of griping about this problem; especially as the government was planning to build more central area flats.

To level the playing field, the government rolled out the Prime Location Housing (PLH) model in 2021; now expanded into the Plus and Prime framework (from 2024 onwards). These flats in choicer locations still come subsidised, but with stricter conditions:

- Longer MOPs (10 years instead of five),

- Subsidy clawbacks when you sell,

- Rental restrictions (you can’t rent out the whole unit, even after MOP),

- An income ceiling that applies to resale buyers too.

At the same time, another lottery effect disappeared: the Selective En bloc Redevelopment Scheme (SERS).

For your parents’ generation, SERS created a “hope premium.” Even if they bought an ageing flat with 60 years left on the lease, they could still tell themselves: “Maybe one day this block gets picked, and I’ll be offered a new lease nearby.”

After 2017, it became clear that there was a faint hope; only about five per cent of all flats would ever be eligible. But recently, the government confirmed that the last SERS exercise is over, to be replaced by the less generous VERS (Voluntary Early Redevelopment Scheme). VERS won’t kick in until the 2030s at the earliest.

So in effect: no more HDB lottery, no more SERS, and tighter restrictions on Plus and Prime flats, if you still want a central location. Again, this was done to make things fair for you and your generation – but the price of that fairness was your exclusion from prior potential windfalls.

Conclusion: all of this helps your generation in a collective, big-picture way; but that may sound like a hollow platitude

When you zoom out, all of these changes – tighter loan rules, smaller and hence more affordable unit sizes, no more SERS, the end of the “HDB lottery” – make sense. They create a housing market that’s at least a little bit less speculative, less prone to bubbles, and fairer across the board.

Collectively, your generation is less likely to see homes become a runaway asset class, or watch the whole market swing violently up and down. That’s from the lessons we learned in previous decades.

But on the individual level? That’s harder to swallow. You’re being asked to accept stricter loan caps, higher down payments, probably smaller homes, and fewer “lottery ticket” moments – all in exchange for stability that feels like an abstraction.

On paper, the system is fairer and safer. In practice, it can be tough to swallow. No one has sufficient pom-poms and cheerleading skills to make you smile about that, but the market really did change under your feet. If buying feels harder now, it’s because it is; The rules were rewritten just before it was your turn to play, and ironically it was to make it fairer.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

Why is it harder for young Singaporeans to buy a home now?

How do years left on the lease affect HDB prices?

Why are new condos smaller today than in the past?

How does being self-employed impact home loan approval?

What changes were made to make HDB flats fairer for buyers?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Pro This 130-Unit Boutique Condo Launched At A Premium — Here’s What 8 Years Revealed About The Winners And Losers

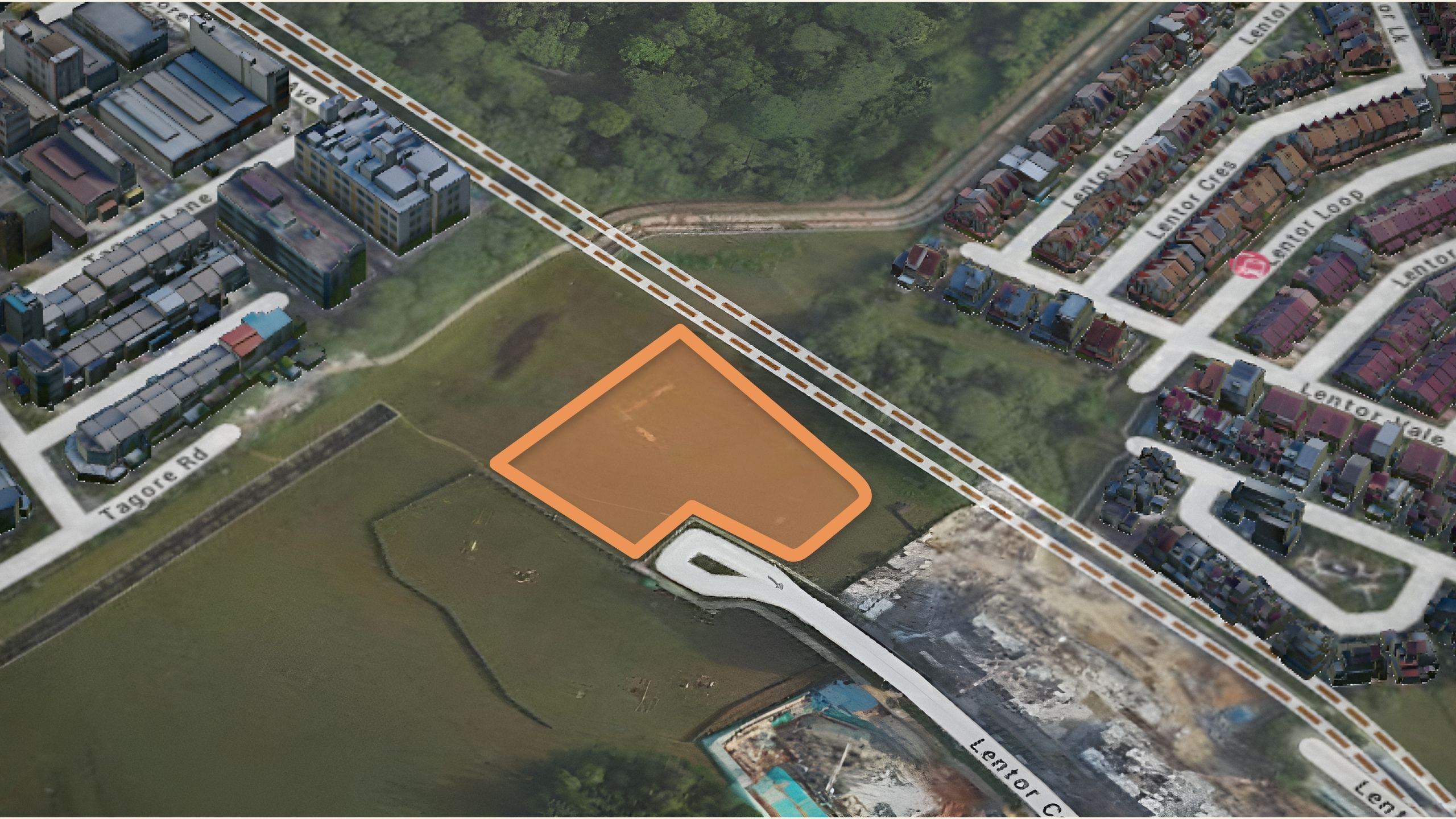

Singapore Property News New Lentor Condo Could Start From $2,700 PSF After Record Land Bid

On The Market A Rare Freehold Conserved Terrace In Cairnhill Is Up For Sale At $16M

0 Comments