How Condo En-Bloc Sales Became A Speculative Exit Strategy In Singapore

September 25, 2024

En-bloc sales and private property go hand-in-hand; some Singaporeans even claim that en-bloc potential is the main advantage of old private homes. But elements of the trend may be newer than you think, and en-bloc sales didn’t quite work the same in the past. Here’s a look at how collective sales came to be seen as a windfall, and about how it used to be:

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

Where did the en-bloc phenomenon come from?

This refers to the collective sale of properties to a buyer. In most private homeowners’ minds, this happens when a condo project gets too old, and a sufficient number of owners agree to sell the entire project to an entity for redevelopment.

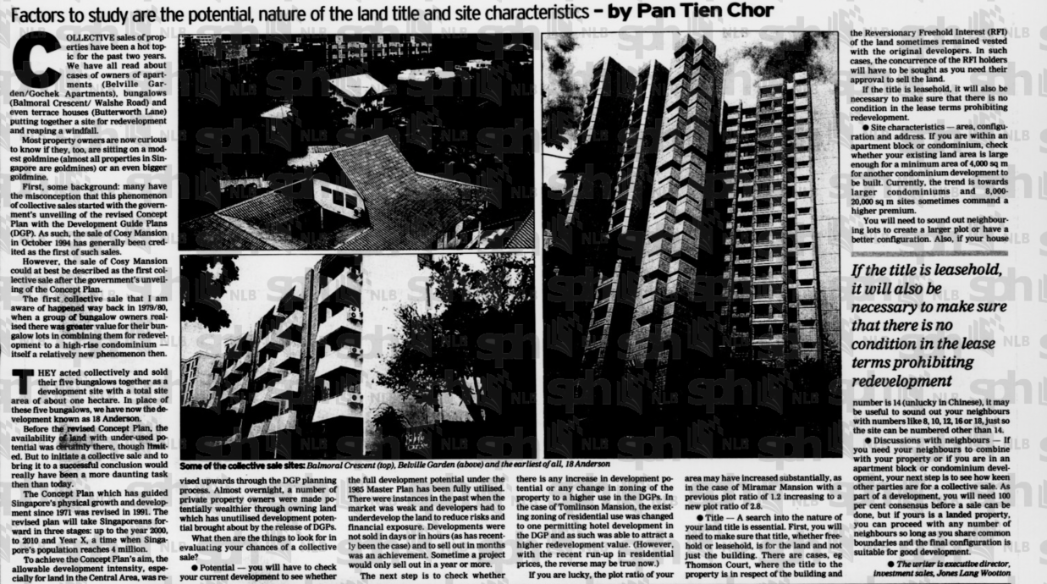

The very first en-bloc sale and redevelopment of this kind was allegedly five bungalows that were redeveloped into Anderson 18. This is contrary to claims that the first en-bloc was Cosy Mansions; we sourced this from a report in The Business Times, which claims the Anderson deal happened earlier in 1979/80*.

In the same linked report, you can also see what started the en-bloc interest: the Development Guide Plans (DGPs). Once the government began releasing information on future zoning/planning intent, developers as well as groups of sellers were able to see the potential opportunities and work together. Prior to this, the Master Plan only showed existing developments and zones, not future plans.

Today we don’t have DGPs any more (the last of 55 DGPs was for the Punggol area in July 1998) but we now incorporate future zoning and urban planning into the Master Plan.

*As an interesting aside, the article warns of Reversionary Freehold Interest (RFI), which is a leasehold property built on freehold land. This is an ongoing issue, and the report shows it’s been with us from the start.

It was actually the government who made en-bloc sales easier

Today, you need 80 per cent consensus by share value and strata title area, for an en-bloc to proceed (90 per cent for developments 10 years or newer). But this wasn’t the case: prior to 1999, a single property owner could object and stop the entire en-bloc.

It was in November 1997 when the government first mentioned it wanted to make en-bloc sales easier. This was in the interest of the country as a whole: to better accommodate a growing population, it was essentially that older properties with few units make way for denser high rises, with increased plot ratios. At the same time, it was recognised that en-bloc sales prevent urban blight: redevelopment stops us from accumulating a mess of deteriorating buildings, which pose health hazards (structural issues, vermin, and so forth).

If the free market can deal with this, with residents “evicting” themselves and developers bearing the cost of urban renewal, so much the better for the public and the taxpayer. So it was that the Strata Titles (Amendment) Act of 1999 allowed a situation where the majority could overpower a minority, even in the context of selling their home. On the flip side, this may be a necessary solution to free up plots like freehold or 999-year leasehold land, which may otherwise never be developed for higher-intensity use.

For a time, the Method Of Apportionment (MOA) in en-bloc sales made mixed-use units unpopular

The MOA refers to how sale proceeds from an en-bloc are distributed. One of the earlier common methods was simply to go by Share Value, an issue which we discuss in this article.

More from Stacked

10 Cognitive Biases That Are Affecting Your Property Purchases!

Sentosa.

But apart from being unfair to owners of larger units, this also ended up making mixed-use projects harder to sell. The reason is that the commercial spaces in the building can be valued very differently from residential. Consider, for example, a space being used as a restaurant: one that has operated for many years, such as Mookata in the former Golden Mile Complex: what is its value compared to a residential unit?

If we just go by strata area, it doesn’t make sense. The restaurant could lose a massive chunk of revenue, as well as long-time customers, by being forced to move. It’s arguable that a homeowner – who has probably also paid less for maintenance over the years – is suffering a much smaller loss.

But “rational” doesn’t equate to “acceptable,” and not every residential unit owner is going to accept this argument.

For a time, this resulted in murmurings that mixed-use projects were at a disadvantage for en-bloc sales. It was believed that collective sale potential was more limited, given the likely objections.

Today though, this is less of an issue (which isn’t to say it’s disappeared altogether, en-bloc sales are always contentious). More complex MOAs tend to be used now, such as ⅓ share value, ⅓ valuation, and ⅓ strata area, or others. The real estate firms and developers have become more adaptable, and the authorities seem happy to allow this sort of flexibility.

The origin of “Freehold is better than leasehold for en-bloc sales”

This was disproven during the en-bloc fever in 2017, but it is a longstanding belief that developers prefer freehold. In theory, freehold is better as there’s no need to top up the remaining lease. However, there’s an older reason:

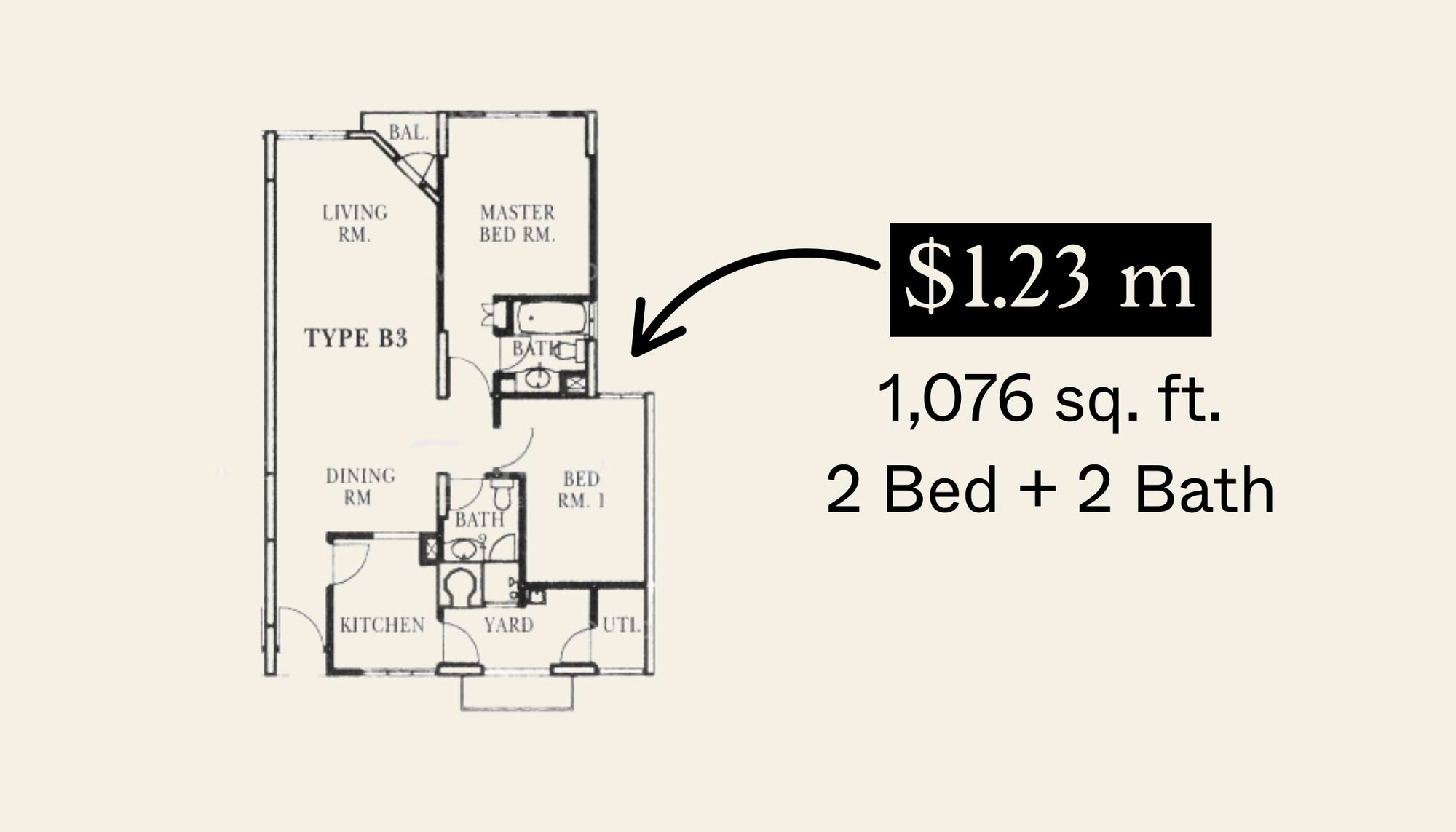

Prior to the ‘00s, it was widely believed that developers would have little interest in 99-year lease properties. What could a developer do with land that has, say, 70 years lease remaining? It was assumed that Singaporeans would be uninterested (although time and again, the market has stunned analyst assumptions; such as with the 60-year lease Hillford).

It was only around ‘04, with the en-bloc sale of Eng Cheong Tower, that the lights went on for leasehold. During this sale, the government had earlier agreed to allow a top-up of the lease, from a remainder of 65 years back up to 99. Once this was established, developers started to see equal potential in leasehold plots.

So whilst the theory that freehold is “better for en-bloc” still remains, we might be seeing a change of opinion further down the road.

While en-bloc sales are still speculative, and not something we’d bet on, we can see it’s come a long way: from being a relatively new and shaky idea, where one objection could sink the attempt, to a much fairer and easier process today. It may also equal the playing field between leasehold and freehold, given that both types tend to go en-bloc before they reach 40 years old anyway.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

What is an en-bloc sale in Singapore property market?

How did government policies influence en-bloc sales in Singapore?

Why are mixed-use property projects considered less favorable for en-bloc sales?

Is freehold land always preferred for en-bloc sales over leasehold land?

How has the process of en-bloc sales evolved over time in Singapore?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

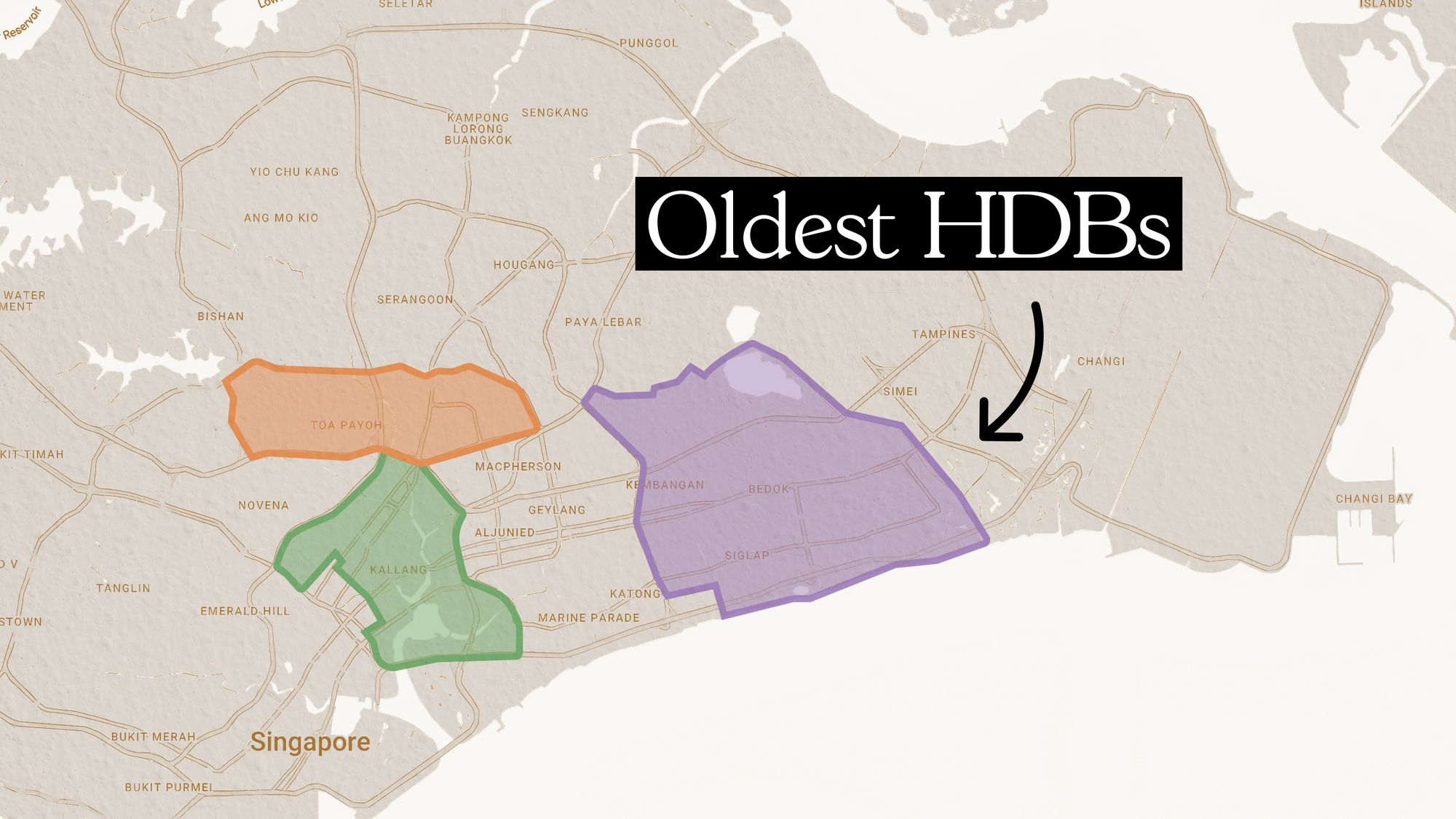

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News REDAS-NUS Talent Programme Unveiled to Attract More to Join Real Estate Industry

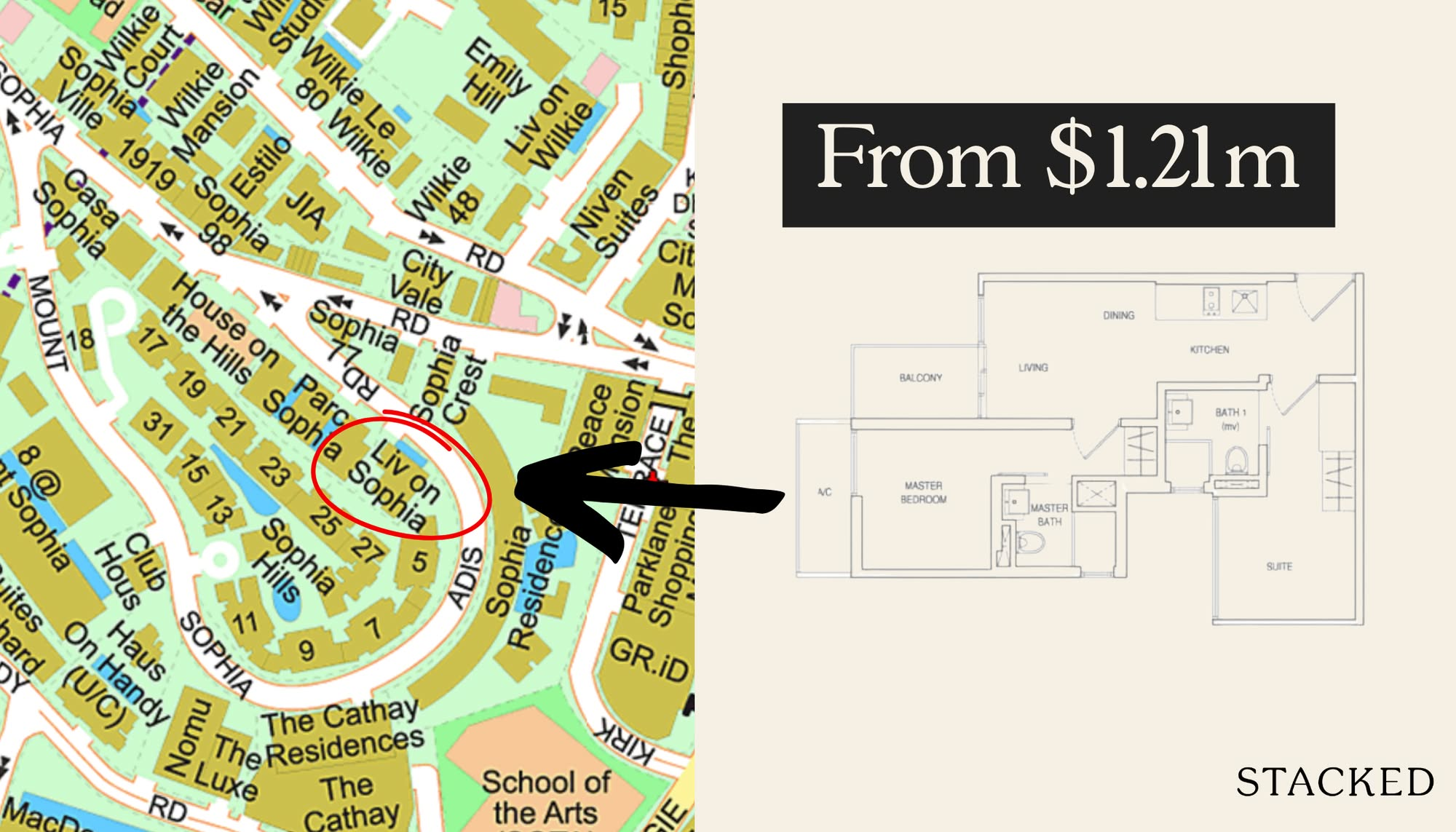

Singapore Property News Three Very Different Singapore Properties Just Hit The Market — And One Is A $1B En Bloc

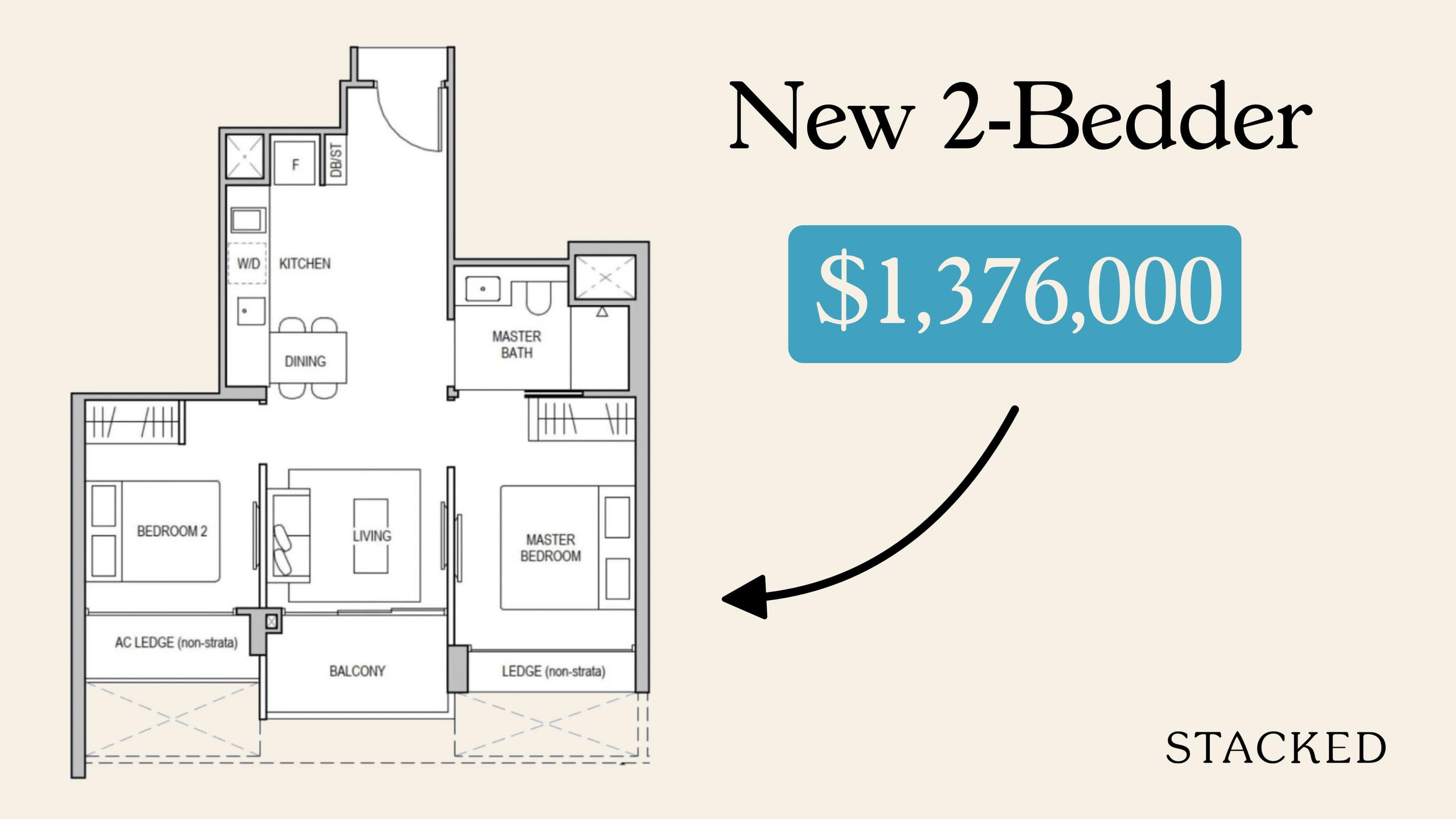

On The Market Here Are Hard-To-Find 3-Bedroom Condos Under $1.5M With Unblocked Landed Estate Views

0 Comments