Could We See More Property Cooling Measures In 2021?

January 22, 2021

In an “oh no” moment on 18th January, Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat said the government is paying close attention to the property market; and that they “don’t want to see the property market run ahead of the underlying economic fundamentals”. This was coupled with a warning that developers should “remain prudent” in their land bids.

This has been interpreted to mean further cooling measures, if the Singapore property market continues its climb. But how likely is this to happen, and is the property market really “ahead” of underlying fundamentals? Let’s take a closer look compared to previous eras:

Why is the government alarmed about the property market?

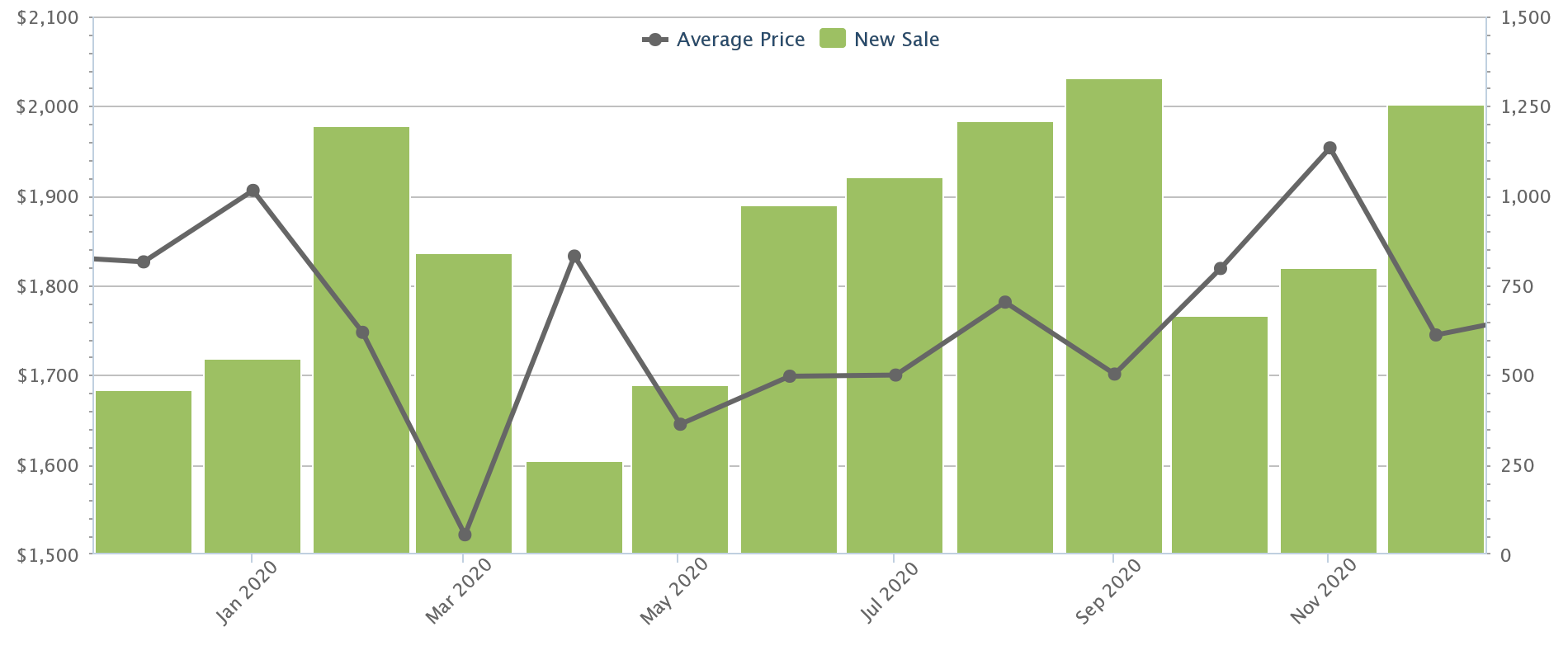

Most of the alarm stems from Q4 2020, which saw a surge in new launch transactions.

Previously, it was assumed that the property market would lose some momentum toward the end of the year. It was thought the pick-up in sales after the Circuit Breaker (CB) was due to pent up demand. Between April to June, new home sale had already risen from 262 to 974 units.

However, the momentum didn’t slow except for a brief period between September and October. To close the year, new launch sales rose from 797 to 1,252 units between November and December; a 57 per cent jump.

For reference, we’ve included new launch sales from December 2019. Note that at the time, new launch sales numbered a mere 456 units.

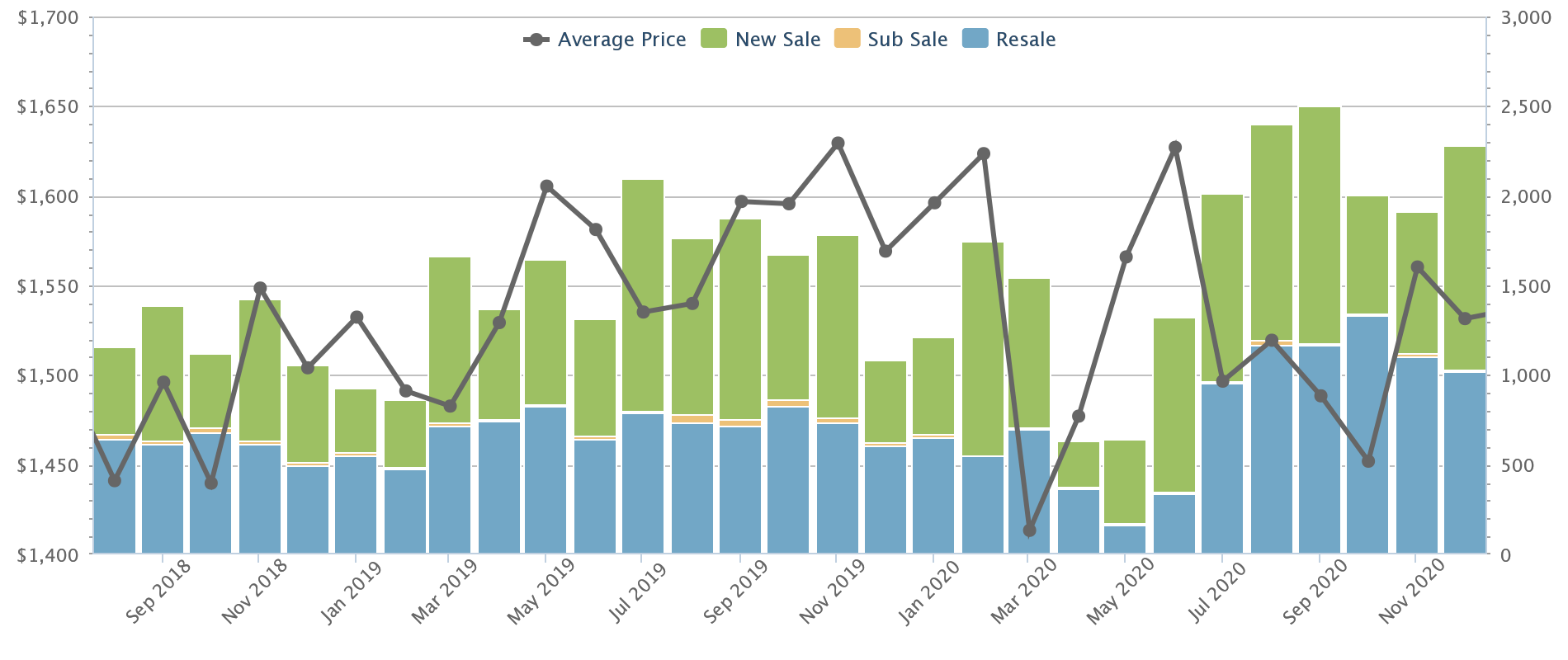

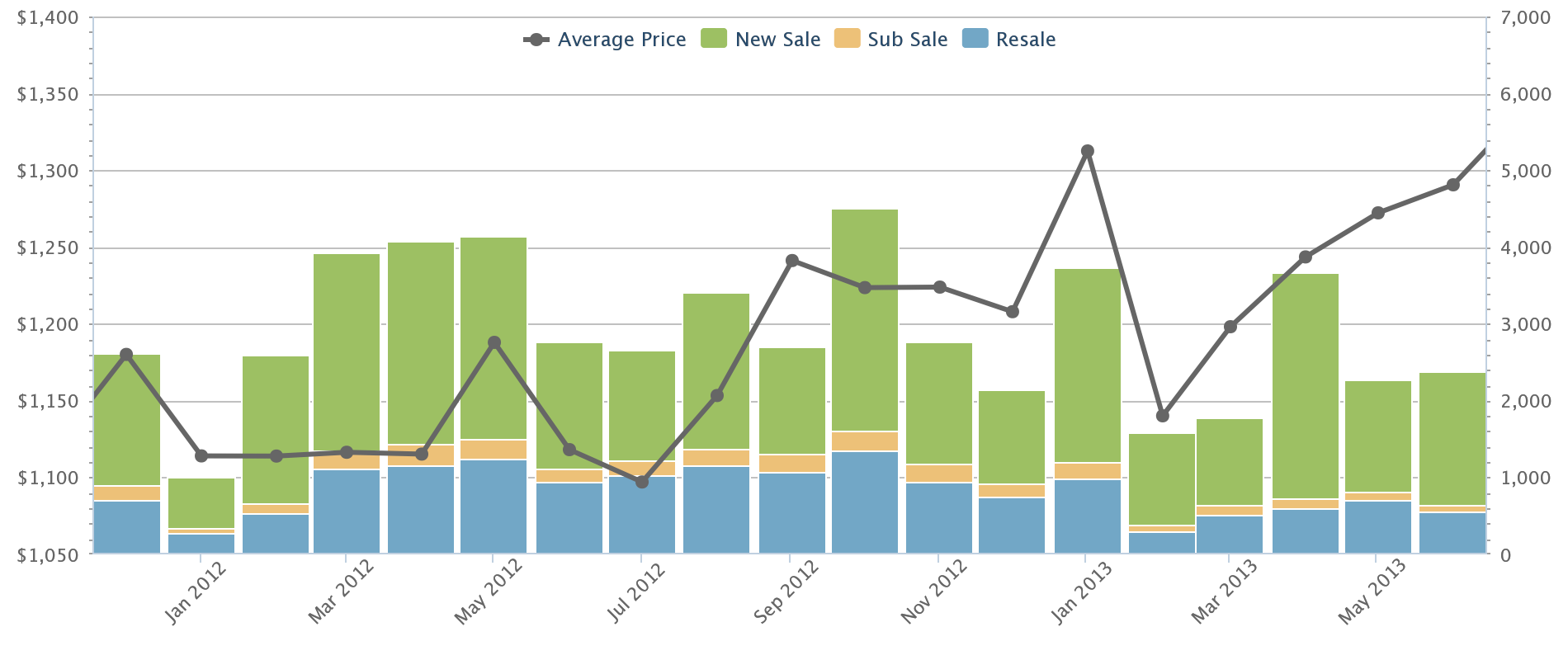

Private home prices in general have also showed a recovery, since the last bout of cooling measures

Putting aside the CB period, the last slump in the Singapore private property market was in the aftermath of the July 2018 cooling measures. By August 2018, when the cooling measures began to bite, prices had dived to a low of $1,441 psf:

But the slow creep-up started again. By end-December last year, median private home prices had risen to $1,532 psf. This is a 6.3 per cent increase, since the last bout of cooling measures.

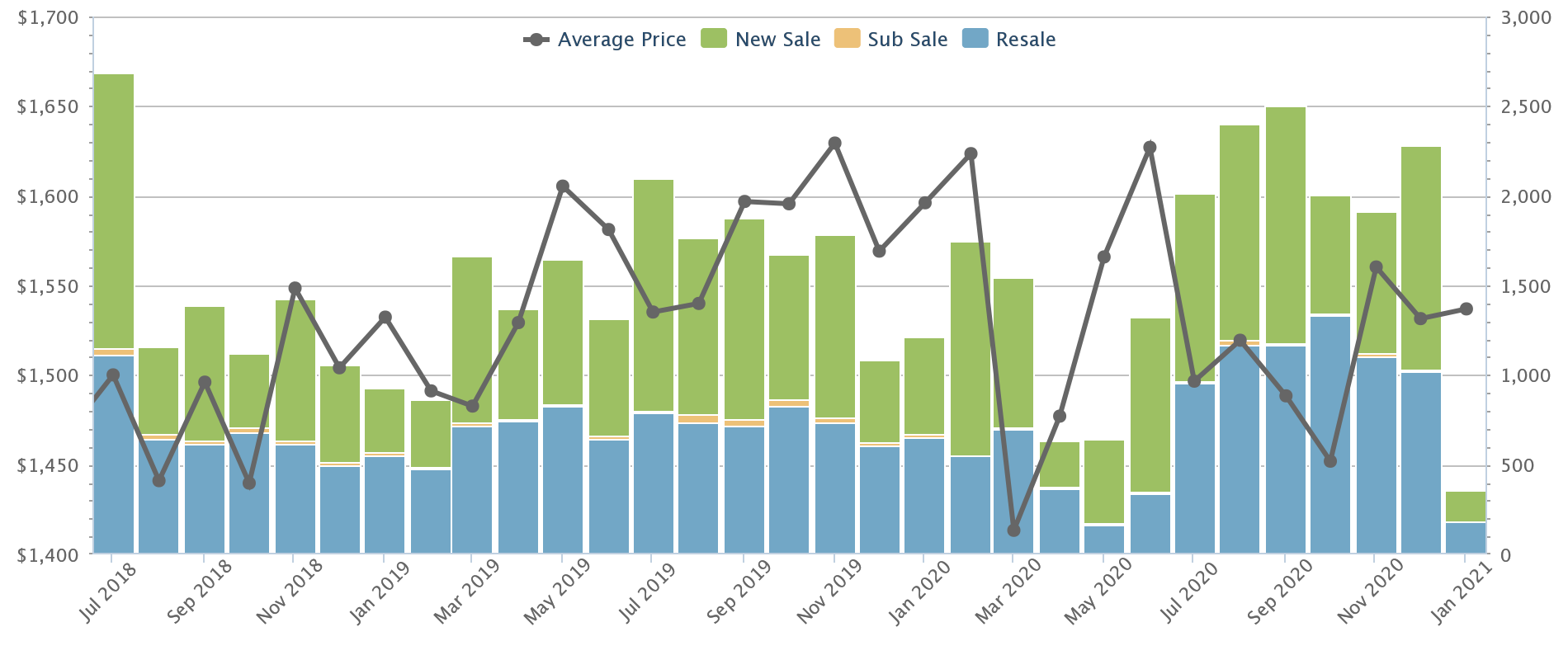

So far, the market’s rise hasn’t been as sharp as events preceding the 2018 cooling measures

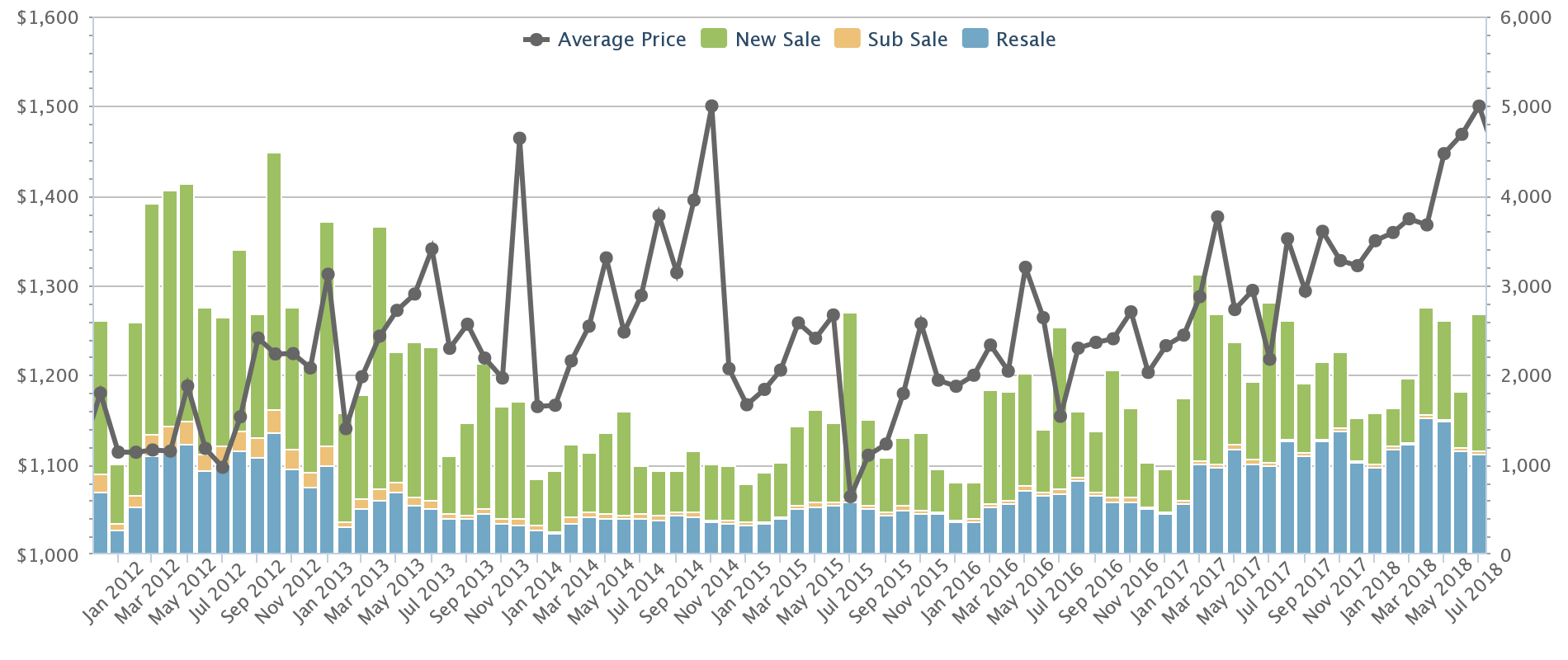

The first cooling measures were implemented in 2009, but there was still no ABSD at the time (just the Sellers Stamp Duty, or SSD, and some loan curbs for those with outstanding mortgages).

The ABSD era – which is widely considered the first “major” cooling measure, appeared on 8th December 2011. ABSD has since been intensified over the years.

As such, we examined how much prices had to increase from December 2011, before the government intervened.

In December 2011, after cooling measures, median property prices stood at $1,180 psf across the board.

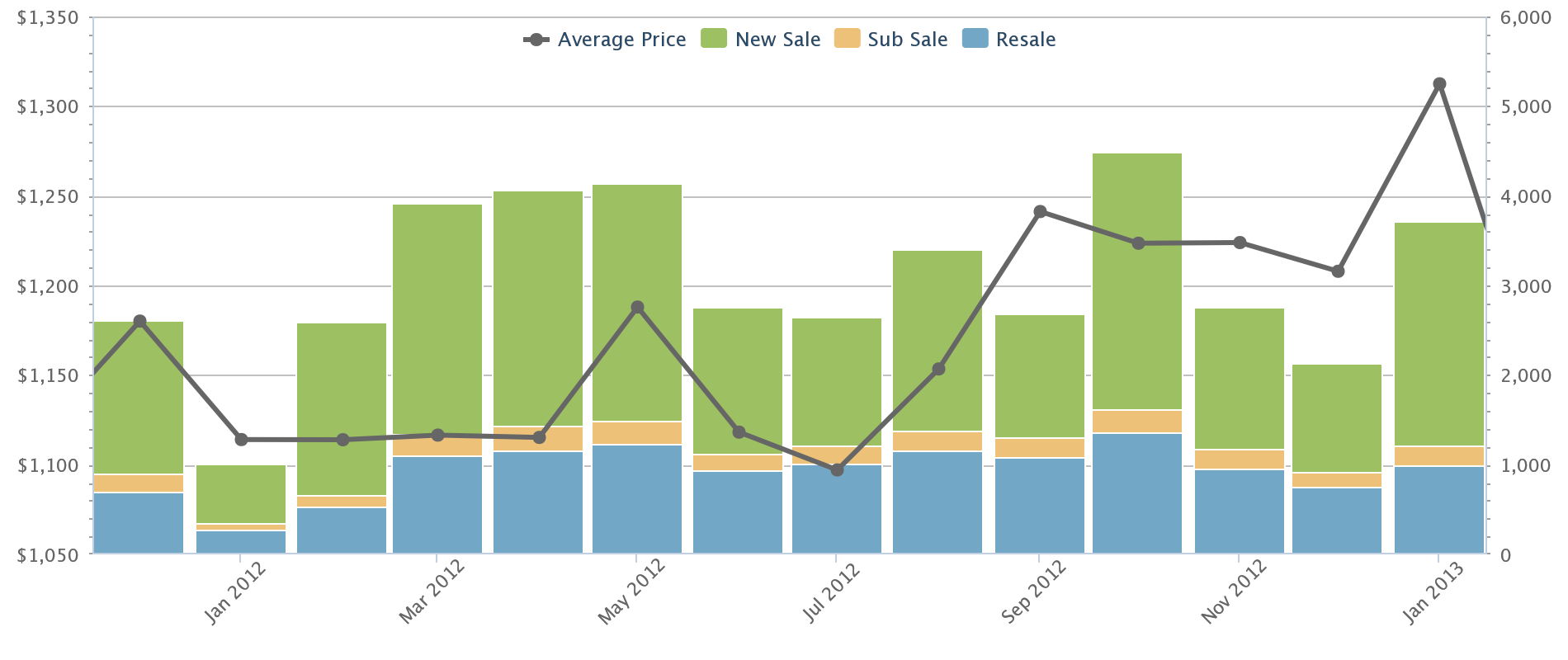

Intervention 1: January 2013, following a price increase of about 11 per cent

The first intervention came in January 2013, when property prices continued to rise to $1,312 psf:

After a price increase of about 11 per cent, the government hiked ABSD by five to 15 per cent.

This was also followed by the implementation of loan curbs, like the Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR), which limited monthly loan repayments to 35 per cent of monthly income for HDB properties.

Intervention 2: June 2013, following a price increase of 13.2 per cent

Prices fell to $1,140 psf in February 2013, after the new cooling measures. But by June 2013, they had again risen to $1,291 psf. This was around a 13.2 per cent increase.

The government then imposed the Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR), capping loan repayments to 60 per cent of monthly income.

Intervention 3: July 2018, following an 11.8 per cent increase

Following the June 2013 measures, prices dipped several times, falling to the lowest point of $1,064 psf. However, by July 2018, prices stood at $1,500 psf.

This was around 11.8 per cent higher than June 2013, and an overall 27.1 per cent increase since the ABSD first appeared in 2011.

This led to the latest round of cooling measures, which raised ABSD by another five to 15 percentage points, and tightened the LTV ratio to 25 per cent (among other measures).

As mentioned above, prices have still managed to rise to $1,532 psf as of end-December; just above the median home price in July 2018.

From what we’ve seen so far, cooling measures tend to be enhanced whenever overall home prices rise beyond 10 per cent

Given home prices are up around 6.3 per cent since the last bout, we may be around halfway to the next cooling measure. However, there’s worry that the government may intervene a lot sooner this time, due to a number of conditions:

More from Stacked

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

This Former School Site May Shape A New Kind Of Lifestyle Node In Serangoon Gardens

A former school in Serangoon Gardens might come back to life as a lifestyle destination after the Singapore Land Authority…

- Wider economic contraction

- The end of Covid-19 support measures

- Rock-bottom interest rates

- A bumper crop of HDB flats reaching their Minimum Occupation Period

1. Wider economic contraction

To date, the Singapore has shrunk 5.8 per cent in preliminary findings, and we’re not yet through the Covid-19 pandemic. Singapore is an export driven economy, which means barriers to world trade (of which Covid-19 is a major factor) will continue to exert its toll on us.

So why are private home sales still rising for now? Here’s a possible factor: according to research by DBS, it’s lower-income workers, with a take-home pay of $3,000 or under, who have been the most affected to date. This demographic saw the greatest loss of income, with some experiencing drops of greater than 50 per cent.

Private home buyers are not part of this demographic, which could be the reason the Singapore private property market still appears resilient.

But It could be a gamble to assume the downturn won’t eventually affect the higher-income segment; and this could prompt quicker intervention by the government, compared to previous years.

2. The end of Covid-19 support measures

As of December 2020, some Covid-10 support measures came to an end. With regard to the housing market, the most significant would be the end of mortgage deferment schemes.

This previously allowed home owners to defer their entire mortgage repayment, or to pay only part of the mortgage.

Outside of the property market, we also need to consider the eventual end of tax rebates given to landlords, job support schemes, etc., all of which could impact continued housing affordability.

In short, it’s possible that the pick-up in private home sales was riding on the back of these support schemes; and that we may see a rise in fire sales or mortgagee sales, should they come to an end.

3. Rock-bottom interest rates

We’ve covered this in a previous article. To quickly summarise, the average interest rate for home loans is now at 1.3 per cent, or about half the HDB loan rate; for a time, there were loan packages below one per cent per annum.

We already witnessed the effect of this after the last Global Financial Crisis – it led to a surge of property purchases, as investors pulled out of assets such as equities and bonds, and re-invested in real estate. With the home loan rate below the risk-free CPF rate of 2.5 per cent, many investors view a mortgage as “borrowing for free”.

The government hasn’t forgotten the huge run-up in property prices from 2009 to 2013, which were partly fuelled by cheap loans.

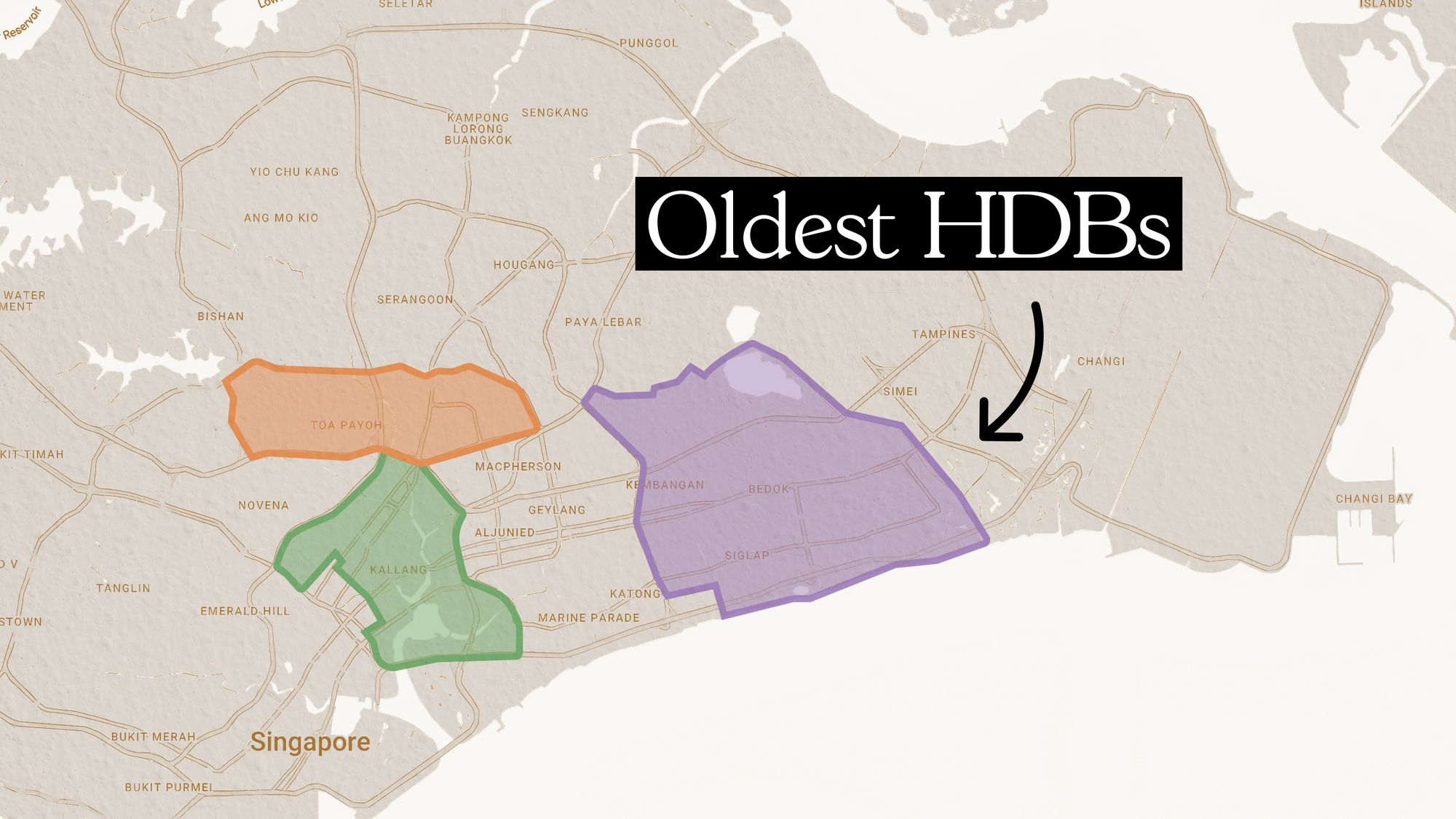

4. A bumper crop of HDB flats reaching their Minimum Occupation Period (MOP)

We’ve covered this in detail in a previous article. To summarise, there’s an uncommonly large number of flats reaching MOP in 2020 and 2021 – about 50,000 in all. This has resulted in a tide of new upgraders, which have been a major market driver since as early as 2019.

Cooling measures could be implemented to balance out any “upgrading frenzy”, especially in light of Covid-19.

Sales results in Q1 could be a determining factor for new cooling measures

If we don’t see some moderation in sales numbers or prices in Q1, the market may well draw new property cooling measures. However, the agents and market watchers we’ve spoken to have a common consensus: the cooling measures are more likely to take the form of loan curbs, rather than higher stamp duties.

This is because the main purpose is to prevent over-leveraging, as opposed to trying to keep housing prices affordable. As we mentioned above, the median price is currently $1,532 psf, which is only just slightly over the $1,500 psf in 2018.

In any case, we encourage readers not to rush into property purchases, for fear of higher stamp duties later. Yes, you may miss out if new property cooling measures suddenly kick in – but property is a long-term commitment, which you cannot quickly liquidate. It’s better to miss an opportunity, than to take painful losses from buying something you can’t afford.

In the meantime, follow us on Stacked so we can keep you updated, as well as provide in-depth reviews of any properties you’re considering.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Editor's Pick

Property Market Commentary A 60-Storey HDB Is Coming To Pearl’s Hill — The First Public Housing Here In 40 Years

Property Advice These Freehold Condos Near Orchard Haven’t Seen Much Price Growth — Here’s Why

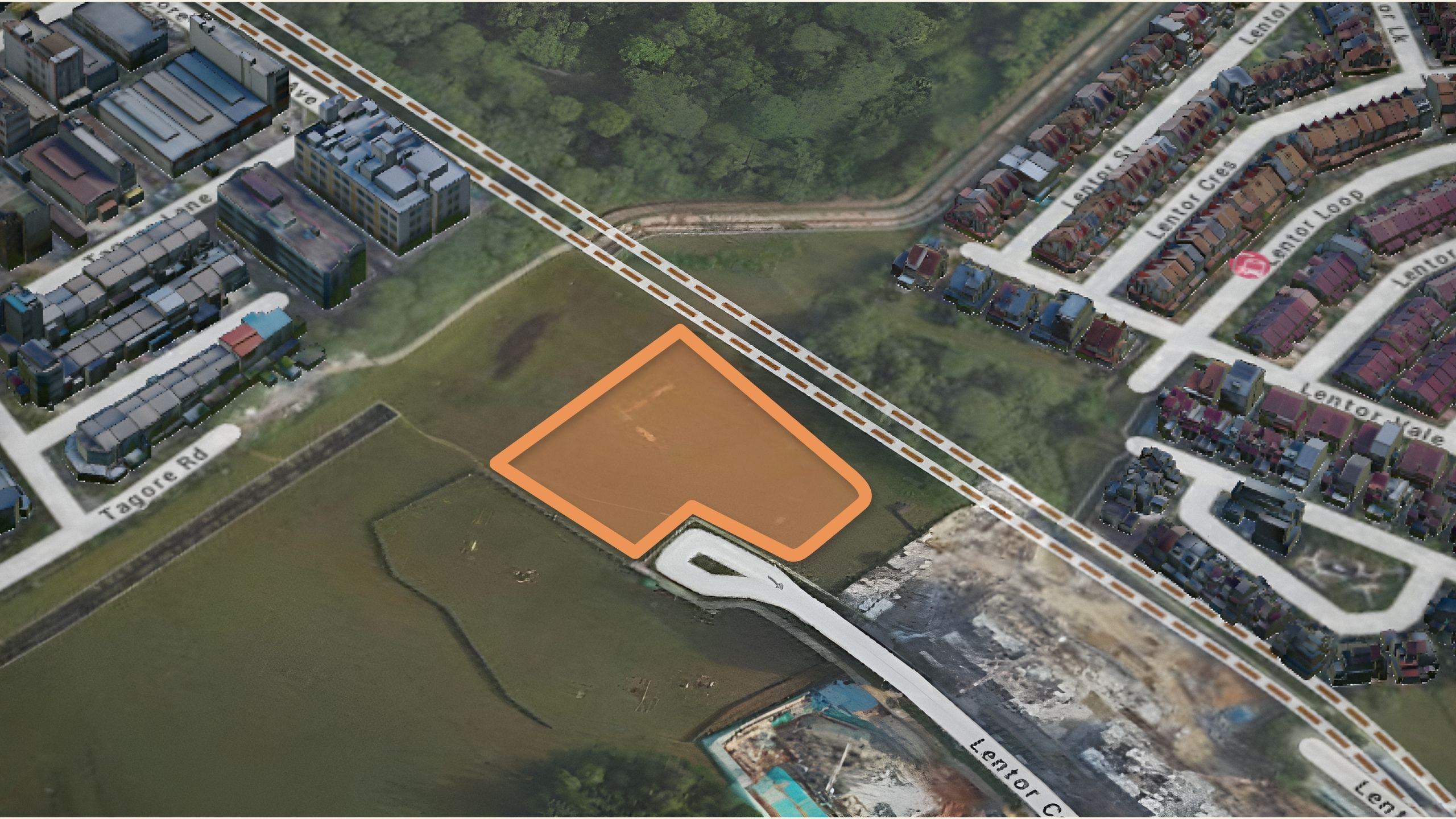

Singapore Property News New Lentor Condo Could Start From $2,700 PSF After Record Land Bid

On The Market A Rare Freehold Conserved Terrace In Cairnhill Is Up For Sale At $16M

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News This Rare Type Of HDB Flat Just Set A $1.35M Record In Ang Mo Kio

Singapore Property News A Rare New BTO Next To A Major MRT Interchange Is Coming To Toa Payoh In 2026

Singapore Property News New Tampines EC Rivelle Starts From $1.588M — More Than 8,000 Visit Preview

0 Comments