With Singapore’s Population At 6.04 Million, Who Wins And Who Loses In The Property Market?

October 2, 2024

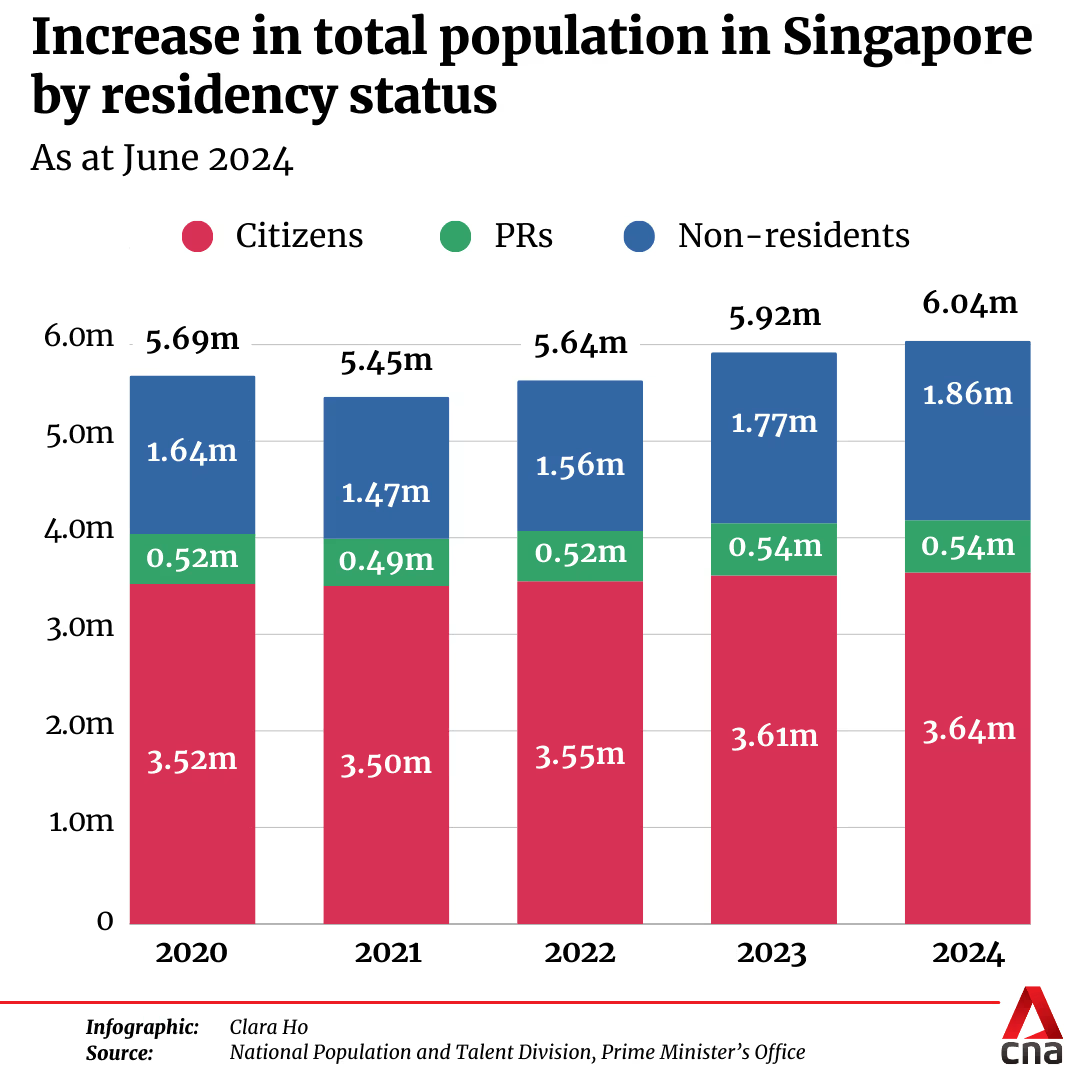

There’s been quite the uproar about Singapore’s population reaching a historic high of 6.04 million, mostly driven by non-residents (their number rose by around five per cent over the previous year). This is a sore spot among many Singaporeans, who already feel our tiny red dot is too packed, and that there’s too much competition for resources: chief among them is living space. There’s also an assumption that property owners and landlords may “win” from this, but it’s not quite as clear-cut:

Many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

Let’s start with the obvious: Singapore does feel a lot more crowded

You may have read the commentary that we can mitigate the density with certain architectural elements. I don’t think so, and I think the average Singaporean is going to feel the squeeze.

The linked commentary mentions Pinnacle @ Duxton, which houses some 8,000 people on 2.5 hectares of land. That’s quite the achievement, and I agree projects like Pinnacle manage to avoid feeling crowded. But how many of us can live in a project like Pinnacle? If you can afford the $900,000 to $1 million odd dollars, and have access to some of the best sky gardens or terraces, I suppose you too won’t feel the crowd – but that’s not everyone. In any case, I’d argue that it isn’t so much the sky gardens or terraces that help with demand. Even without those additions, the location and lack of supply in the area are still the main factors for its popularity.

Likewise, the same commentary mentions the development of the Bayshore area, which is a bit ironic. As someone who lives in that area, I would say it’s the opposite example of something that mitigates crowding: the point of living at Bayshore was precisely the seclusion and quiet. And whilst I don’t begrudge the building of a new HDB estate there (I understand it’s necessary), it shows how the need for more housing makes each neighbourhood increasingly packed. One of the very reasons low-density neighbourhoods are so unaffordable, after all, is due to how scarce they’ve become.

Then there’s the use of integrated developments or other mixed-use projects. Whilst it may be a great idea in terms of urban planning, such projects cause their share of congestion and noise. I’ve also met many homeowners who would define living on top of a mall – one connected to a bustling MRT or bus station at that – as their idea of a nightmare.

Also, integrated developments tend to be more expensive. Woodleigh Residences, Lentor Modern, The Reserve Residences, etc. are not the cheapest options in their respective areas; so this is a solution that makes certain financial assumptions.

Likewise, perhaps some of the disgruntledness comes from how land types in Singapore are used. There’s no denying that GCB (Good Class Bungalow) zones occupy large swathes of land, often in prime areas where land is already at a premium. These GCB areas, while prestigious and highly sought after, arguably represent one of the least efficient uses of land. Given Singapore’s limited land resources, allocating such vast areas to a relatively small number of wealthy homeowners raises questions about the equitable distribution of space, especially when housing shortages persist for the middle and lower-income groups.

So let’s not lie to ourselves. Urban planners and architects are not space-warping gods, and the average Singaporean (i.e., those who can’t afford pricey sky gardens or landed enclaves) will feel the squeeze. Coffee shops will run out of seats, trains and buses will involve pressing up against someone’s sweat, and that low-level roar of the crowd will be omnipresent in some areas.

I’m not denying that we may have no choice and that maybe we need this population boom; that’s not my field of expertise. But I do think we should be frank, and acknowledge that we will pay for it in terms of spaciousness and comfort. And those who are priced out of low-density enclaves or the more spacious (read: expensive) projects will bear the brunt of it.

It isn’t fair, but that’s the reality of it.

The ones who lose out the most, are the ones unable to buy their own flats

Pure Permanent Resident (PR) families can’t get BTO flats and must wait three years before buying a resale flat. In the meantime, they’re stuck competing with foreigners in the rental market (unless they’re wealthy enough to even consider a condo).

Lifelong singles, particularly those who absolutely cannot live at home (some are from dysfunctional backgrounds), are going to deal with high rents in both HDB and private properties; at least until they turn 35. This is a very long time to wait, and a large chunk of one’s earnings to pour into rental costs.

More from Stacked

How Buying A Condo With This Agent Resulted In A Huge $380k Loss For This Buyer

If there’s a reason I’ll never be a property agent (besides having the persuasive power of a neurotic pigeon, that…

And finally, we shouldn’t forget the foreigners themselves. While some may blame them for all this (not really fair I think), note that a 60 per cent ABSD means only the wealthiest among them can afford to buy; and in the meantime, they’re going to be squeezed for rent. Barring corporate types with fat housing allowances, they’re not going to suffer any less than Singaporeans who can’t buy HDB flats. At some point, the government will likely have to provide help in essential industries where foreigners are needed (e.g., nurses in hospitals).

So landlords and investors win right? Not quite.

This is an easy assumption to make, but it’s not going to be true across the board. While landlords and investors may see immediate profits from a population boom, there are some issues that may catch them off-guard.

The population boom drives decentralisation, which could impact high-priced CCR/RCR properties

As recent episodes with the transport infrastructure shows, it’s not sustainable to have everyone rushing to and from the same point in the city (which also happens to be the entire country) at the same time of day. This isn’t news, and URA has been decentralising for decades now: this is the reason we have different hubs like Jurong East, Paya Lebar, the Woodlands North Corridor, etc.

As the population increases, the need to decentralise becomes even more urgent. We’ll likely see even more “hub” areas that bleed workers away from the traditional CBD.

Even if the rising population supports rental demand, there’s no guarantee that demand will follow today’s patterns. It’s something to think about, before you commit to CCR or RCR assets.

Land reclamation and rezoning can affect property values

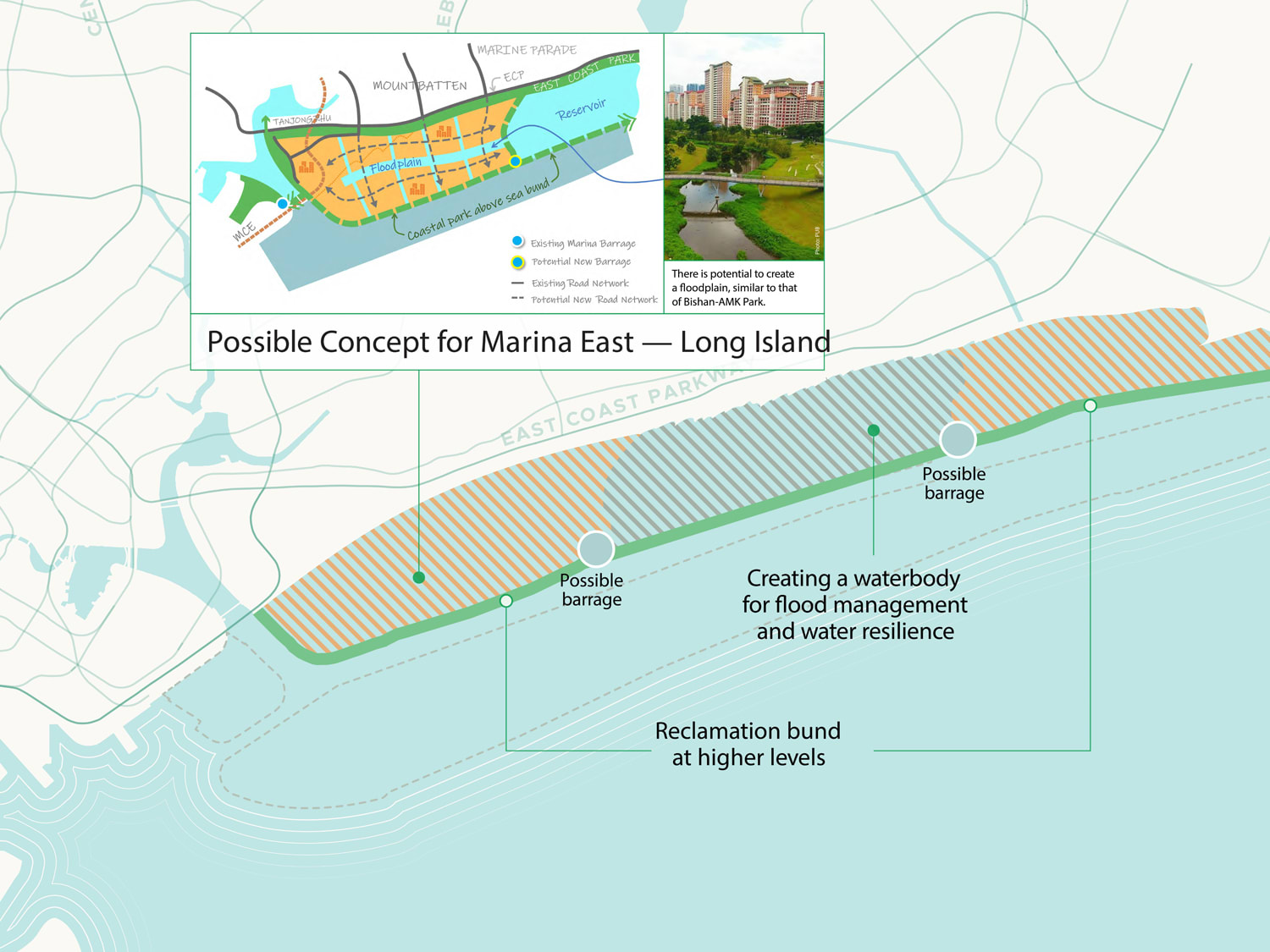

Let’s go back to Bayshore again, since I just used it as an example. When buyers of Bayshore Park, The Bayshore, and Costa Del Sol purchased their properties, it seemed impossible that the view would be seriously obstructed: they were right next to the beach already. That’s until the Long Island project came along, which decades from now could put up some flats in the distance.

Now to be clear, Long Island is more about preventing erosion than having more housing; but I find it unlikely that having more living room isn’t part of the reason. In the distant past, property owners lost their sea view to Marine Parade’s land reclamation for the same reason.

That aside, there’s also the issue of rezoning. Your condo may be in a lower-density area today; but with a rising population, you can’t count on that to last. A mega-project appearing next to you can drive rental rates down permanently, as well as limit resale gains; so not all investors may be cheering the population surge in the future.

Finally, upgraders may be priced out even faster than they think

A rising population could drive up rental and home prices; but it’s dangerous to presume you’ll get to ride that wave. The price gap between HDB flats and condos can widen, even as prices rise across the board. And as urban density increases, landed enclaves will probably climb even higher in value; so that can make it tough for condo owners to make the leap to landed homes as well.

So the rising population may not be an equal boon to all investors and landlords. While they might see some immediate benefits, they shouldn’t get too overconfident with predictions.

Ultimately, an increasing population is one that is probably inevitable, and it could also go some way to support the inevitable wave of HDB flats that would be vacant as the elderly pass on (which we wrote about here). While regulations could help to prevent this from happening, an increasing population can help to cushion this effect.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

Who are the main groups affected by Singapore’s population increase in the property market?

How does the population growth impact property prices and availability in Singapore?

Do landlords and property investors benefit from Singapore’s rising population?

How does the population increase affect the living environment and crowding in Singapore?

What challenges do foreigners face in Singapore’s property market amid population growth?

How might future urban planning and land use policies influence property values in Singapore?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News Why Some Singaporean Parents Are Considering Selling Their Flats — For Their Children’s Sake

Pro River Modern Starts From $1.548M For A Two-Bedder — How Its Pricing Compares In River Valley

New Launch Condo Reviews River Modern Condo Review: A River-facing New Launch with Direct Access to Great World MRT Station

0 Comments