I Spent 24 Hours With Migrant Workers In Singapore: A Behind The Scenes Look At The People That Build Our Homes

July 25, 2022

Buying, renovating, and moving to a new home can be one of the most stressful periods of your life.

The uncertainty of securing a BTO or even a resale condo, to the anxiety of working with a renovation ID (oh, all the horror stories), and juggling the timelines so you don’t have to pay additional rent.

But at the end of it all, being able to return to a cosy roof over your head after a hard day’s work always makes everything seem worth the effort.

And so while everything is all well and good, have you ever stopped to think about who actually builds your homes in Singapore?

When I used to work in social services, I saw many clients who were from other countries. Of course, the most tragic stories would fill you with despair. But it wasn’t so much the harshest stories that you are always stuck with, but how many people had to struggle to get by.

One of the most common profiles would go something like this:

A mother of 2 moved here to settle down, but later found herself divorced. Needing to support her two growing children, she worked from 6 am to 4 pm at KFC. She would take a quick shower before moving to Jollibean to work from 6 pm to 10 pm.

Everyday.

Seeing her work so hard, made me more sensitive to other foreign workers who worked day and night, rain or shine.

What were their lives like? How did they eat? How did they rest? Where did they have fun? Did they like Singapore?

So I followed them for 24 hours, to find out how it was to live, work, and play, from the eyes of a construction worker.

Living in different places

I’m scheduled to meet Chris at 730 pm, my host from WCH Scaffolding, a construction company that focuses on building the outer scaffolding upon which other construction workers can stand to work on. This provides the platform and the foundation upon which they can securely bring their materials and build up the building.

The dormitory is located in Woodlands, and I’ve to walk for 10 minutes from the bus stop before I reach.

When I reach, the people around gawk at me. I look out of place. I’m dressed in a buttoned shirt and jeans.

There’s a gantry that greets me. I’m surprised to find the level of security here. At the entry, there’s a face scanner and a temperature scanner that reads their wrist.

As I peer inside, the workers are bringing their toiletries and preparing for showers.

Chris comes out to greet me. He introduces me to his warehouse, where they store the metal poles needed for the scaffolding. As we stand around, lorry after lorry comes in. Workers hop out, greet Chris, and proceed to their dormitories to rest.

Chris wants to first show me the recreation centre. It’s where the workers go to buy groceries, get food, and relax. When I enter the recreation centre, there is a row of shops. Somewhat off-key singing plays in the background, as an uncle tries to hit the notes whilst singing on stage.

I hope that’s not the only entertainment for them. Shops sell everything, from SIM cards to condoms (because you can’t have a baby in Singapore).

There’s a long queue at the ATM, as workers check if their salaries have been paid. It’s the 7th, and often salaries come in on the 5th.

Chris tells me that workers may sometimes have payments dragged by employers. It pays to be sure.

It’s discomforting to hear another supervisor explain to me that these recreation centres were set up so foreign workers don’t clog up the main shopping malls.

We get some food and sit down on the floor to talk about life. I begin with a topic that I always struggle with – finding love. Despite leaving my number on many post-its and passing them to female friends, these ladies never get back.

But how do the workers here find love? Sometimes Peninsula Plaza, other times, through friend referrals.

Sometimes they go to Peninsula Plaza, see a girl they like, approach them and ask for their number.

No Tinder?

Nah.

It’s hard to be in construction. Two of the managers have been divorced, with the long hours making it difficult for consistent time to spend with family.

These people like coming here because it feels like they are breathing the air back where they were from.

It strikes me. These people are far from home, and searching for home. As they sit with their friends, share beers, as they eat together, and pick foods from each other’s plates, they are rebuilding a sense of home. Where they are known and seen.

They are not just building homes for us, but building a home for themselves.

And perhaps that’s what makes us so discomforted at times, especially when we think Singapore is our home, and perhaps ours alone.

Later that evening, at 945 pm, a worker approaches Mr. Mani, the operations manager, and mumbles a quick sorry.

His eyes are bloodshot, and he looks teary. He starts speaking to Mr. Mani in a language I don’t understand.

I leave them.

I catch snatches of their conversation, and hear the distress in the man’s voice as he shares. There’s an occasional break in his voice.

Then I see him making a slashing motion on his forearm. Is he speaking of self-harm?

Later I find out from Mr. Mani that this man has just experienced his girlfriend being married off. He’s been here working for 7 years. And after 7 years of waiting, his girlfriend’s family had enough of waiting.

They were going to marry her off.

Hearing that story, I wasn’t quite able to process it. What did they sacrifice in the midst of moving to Singapore?

I was only beginning to find out.

The dreams that die

I head into their rooms. Here, there are double-decker bunk beds and 4 fans in the middle of the room. As I head in, the men are on their beds, looking through their phones. They immediately sit up when I come in.

Mr. Mani introduces me as the writer and leaves us to it.

They invite me to sit on the mat, and I start with some questions that I’ve always wondered about. What brought them here? What’s difficult in Singapore? Do they think we treat them badly?

‘Singapore is good’

Kalai, whose name has been changed to preserve the anonymity of the workers, is 26.

That’s my age. But that’s where our stories differ. He was studying in college for 3 years before his family’s financial situation got too difficult for them to support his education. He dropped out to come to Singapore to work.

Another adds,

I wanted to do a government job but after failing the entrance test 3 times, I had to work.

As they sit around on the mat to share their stories, I hear more and more stories like that. People who were studying and then dropped out to support their families. Workers who paid $10,000 to agents to come here. They begged, and borrowed to get enough money to come here.

But why? Why not pursue their dreams, whatever they were?

Because we want to support our family. When they happy, we happy.

They trade their dreams, to love their families.

And upon coming here, they might earn $22 a day. With overtime that might come up to $800 per month. They often sent home $500 a month, and survive on the remaining $300.

How? They broke it down quickly. $142 for catered food for their breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Then $20 for their laundry.

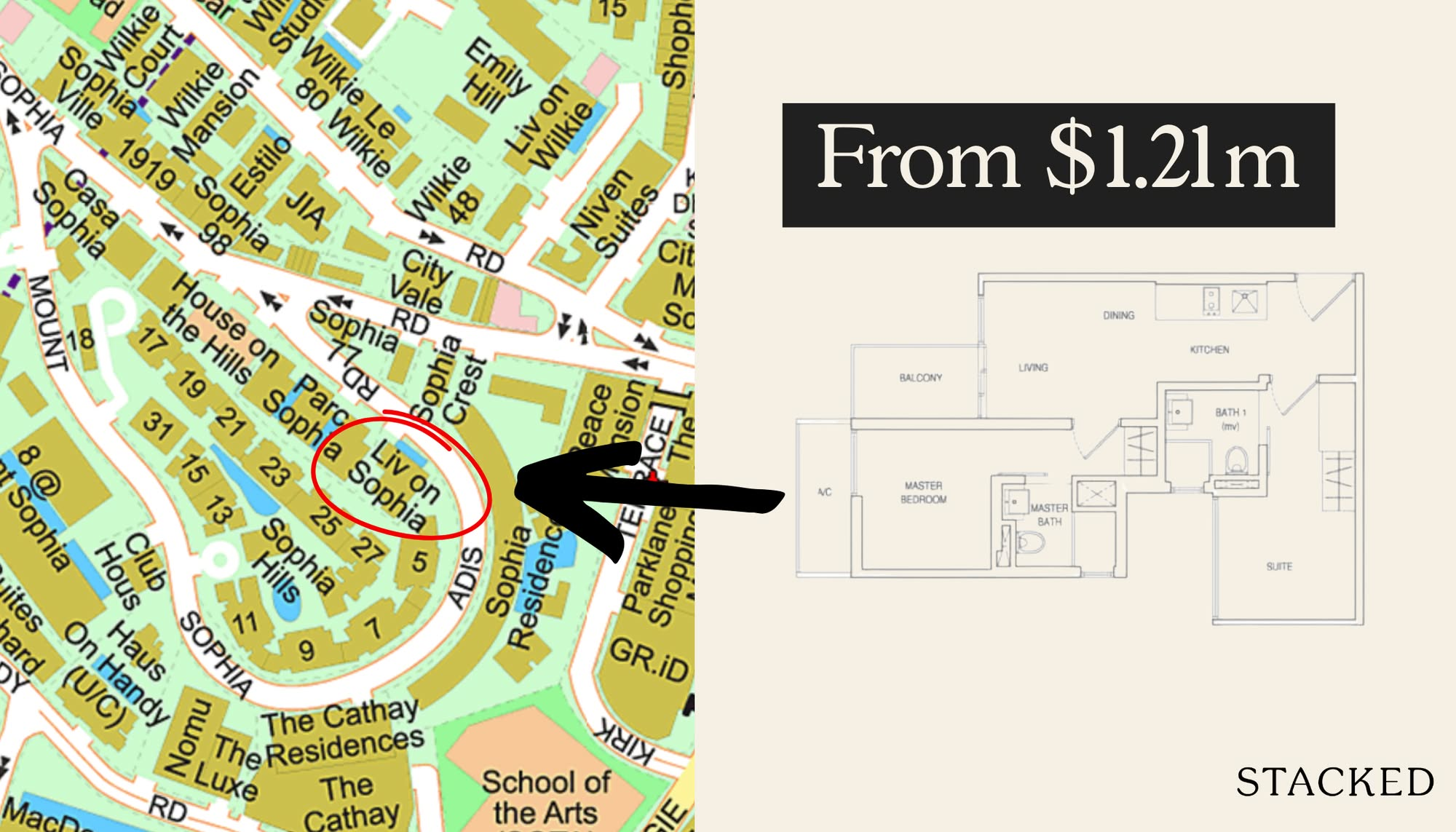

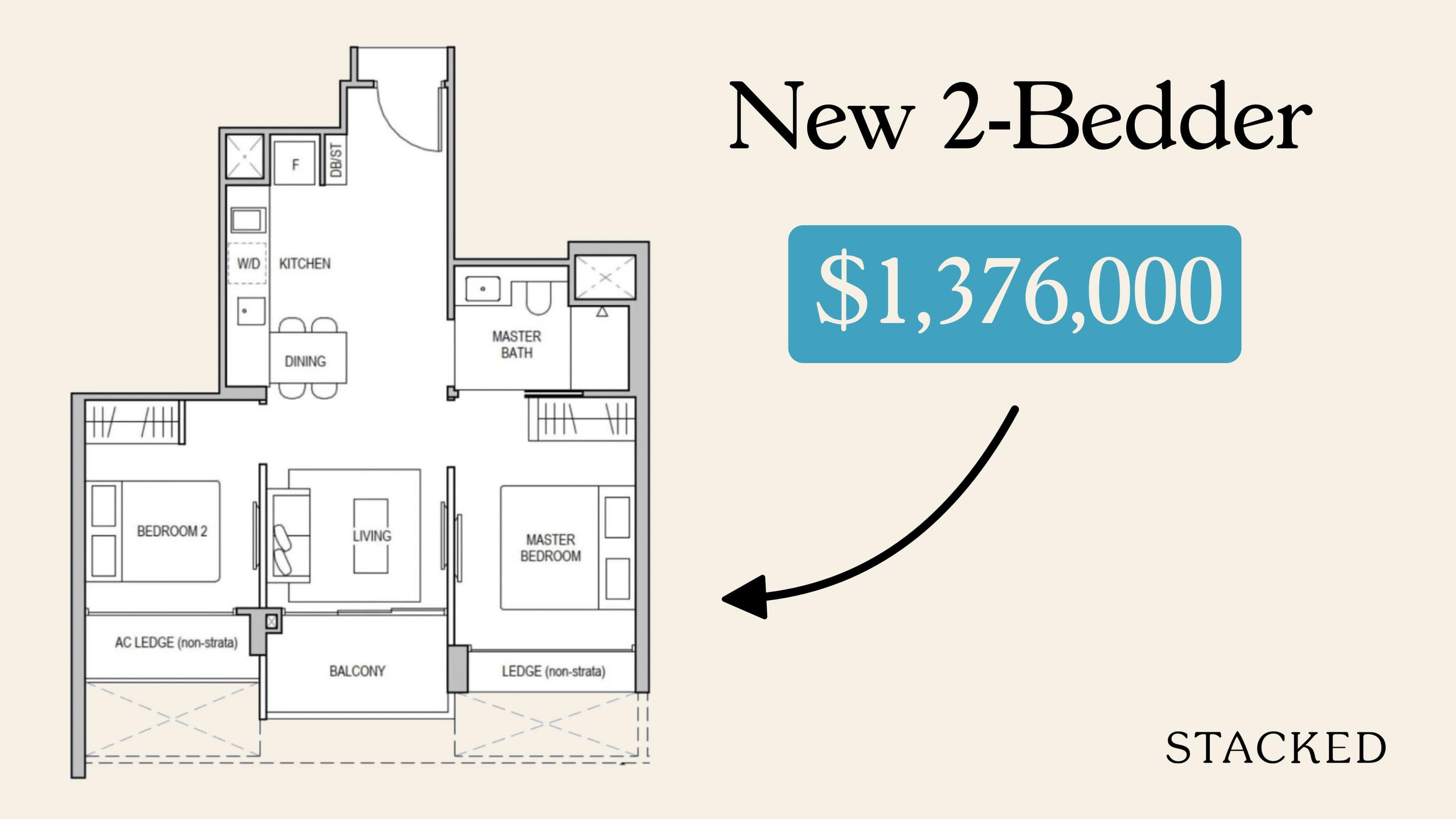

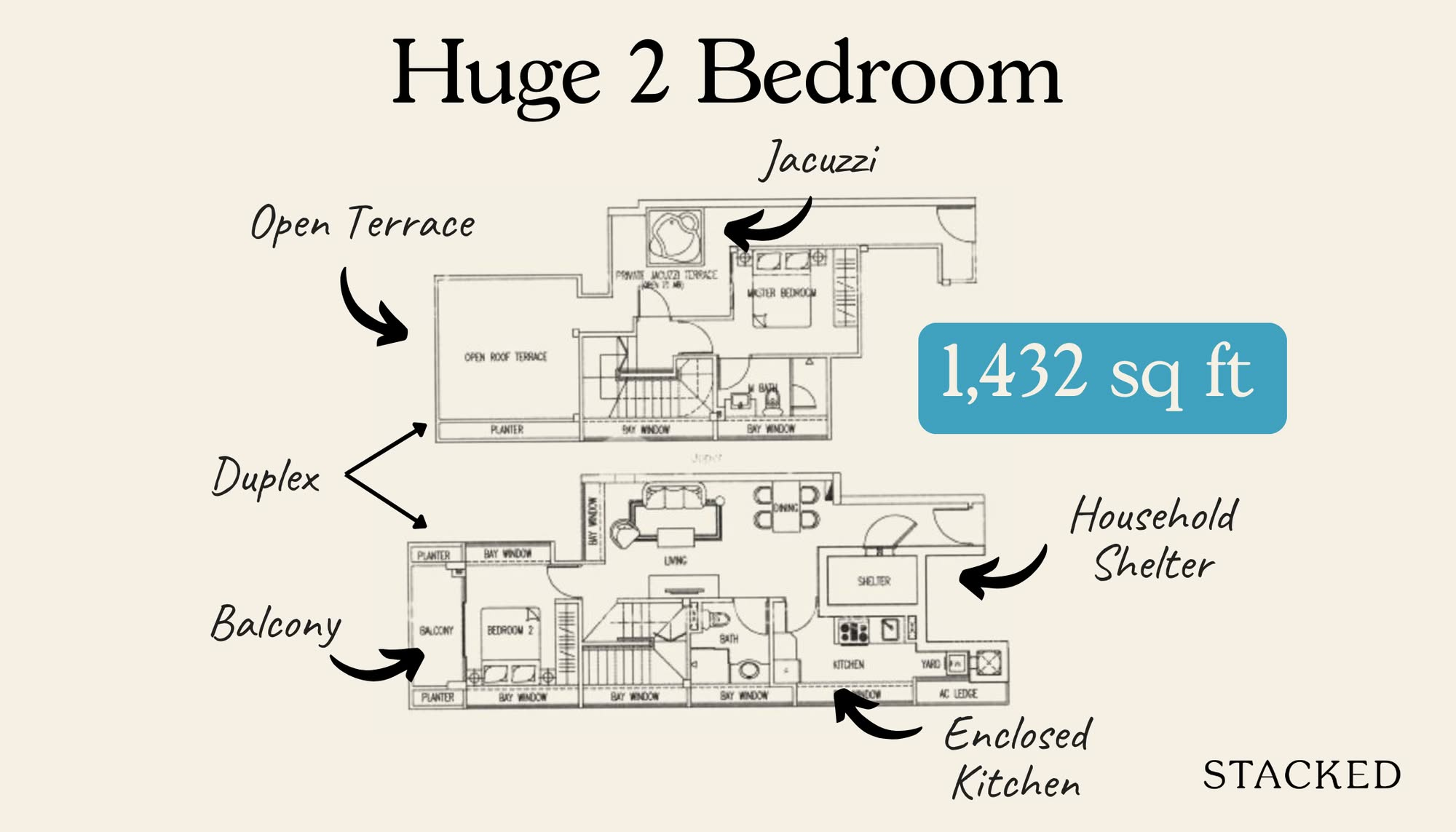

More from Stacked

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

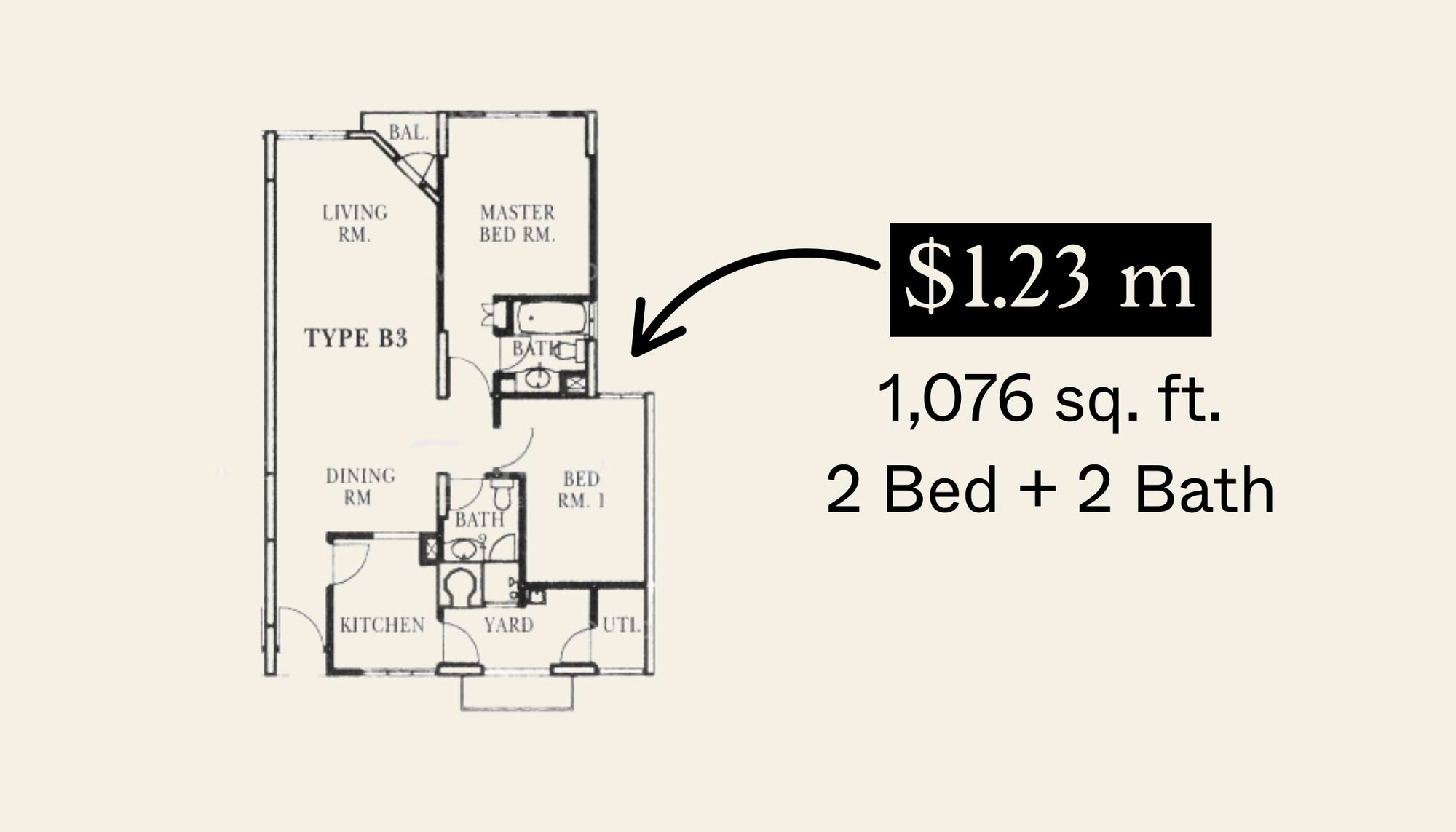

Unaffordable Homes In Singapore Are Causing The Younger Generation To Rent: Is This A Good Idea?

In a recent PropertyGuru survey, two-thirds of Singaporeans aged 22 to 29 said they’re renting because home ownership is still…

The remaining was for their other needs.

Because they were so eager to earn money, they would follow every letter of the law. Even when scam calls came through.

Mr. Mani shared how scammers would frighten foreign workers, saying that they were from MOH, or ICA. These foreign workers would comply, handing over bank details, and OTPs, before finding money quickly siphoned from their accounts.

Over the past week, at least 3 had lost their entire month’s salary. Some banks would refuse to compensate. What could the worker do, except work harder?

I wondered how they persevered despite these. If they wanted to give up. I probed and pushed. I asked at least 3 times what their difficulties in Singapore were. Or if they had experienced bad Singaporeans who weren’t very kind.

But over and over again, they kept saying, “Singapore is very good.”

Really?

They talked about how the income from Singapore allowed them to support their entire family. Or how it was clean. Or how the government still paid them during the lockdown. Or how Singapore always ensured “justice for the worker”.

I was surprised. I didn’t expect this.

After seeing the reports on how we cramped foreign workers in dormitories, I would have expected an outpouring of frustration.

Somehow, there was none.

As they prepare to go to bed, I wonder if they ever feel that sleeping here with people they don’t know, in a double-decker bed, is ever difficult.

But no one complains.

Then we went to work

John!

Chris calls softly. My eyes blink.

It’s 545 am. It’s an early start for me. Heading to the toilet, it’s already crowded.

Workers filter into the toilets. At the eating area, there’s bags of food containing their breakfast and lunch for the day. Some open the plastic bags, turning them over, trying to figure out what’s in them.

I sit with one, striking up a conversation. His metal bowl is filled with a rice-like mixture. It doesn’t look appetising.

Nice?

He makes a so-so sign.

Well, it’s clearly not great.

Soon it’s time to leave.

We climb aboard the lorry. It’s a 40-minute journey to Tuas, and I’m not sure what to expect. Since the days of the army, I never expected myself to sit in the back of a lorry again.

As we travel, most sleep. They lean back on the sideboards, stuff in some music, and sleep.

When we reach the worksite at Tuas, the workers don their vests, and helmets, and standby for a safety briefing.

Then work starts. I wasn’t able to physically handle the equipment because I didn’t take the approved workplace safety courses. But seeing them move the scaffolding, pained me.

I knew that my presence made it more difficult for them to do their work, because being filmed meant that they had to do everything by the book.

Despite the heat and the open air, they still donned their masks. Their faces were caked with perspiration, the perspiration causing the masks to stick to their faces. Under the hot sun, they started with small things like cutting the cable ties.

Then it moved to physically moving the 10kg metal scaffolding up and down the 3m scaffolding.

They never stopped. I heard from one worker that they often work for 2 to 3 hours under the sun before having a rest.

Under the sun, speed is of the essence. There was a rehearsed movement to the construction.

Snip. Clang. Bang!

No movement was wasted. It was almost as if they were conserving every ounce of energy they put in.

They finished this job in an hour. But there was no mess. The scaffold poles were neatly laid in a pile, with a tarpaulin laid under it to prevent it from being dirty.

The workers knelt on the floor, painstakingly picking up all the cable ties to preserve the tidiness of the place.

Suddenly, a subcontractor drove by. Seeing the supervisor, he raised his voice.

Eh, you never ask for my permission before taking down?

What if I haven’t finished?

The supervisor apologised and averted his eyes.

The subcontractor growls,

Next time better tell me first before you do anything.

Later, he explains to me that a lot of construction is about giving face.

He shares the story of how a construction worker once took a mango from a tree. When the owner saw, he shouted vulgarities and threatened to call the police. The supervisor had to give the number of his Managing Director, who later appeased the man with a box of mangoes.

The scaffolding was successfully pulled down, but the job hadn’t finished. There hadn’t been approval to start on the other site.

Quickly, the men pulled out the tarpaulin, took off their shoes, and rested. Some scrolled through their phones, whilst others made calls to their family. You slowly see that the most important things to any construction worker are shade and sleep.

Their lives are a persistent journey from place to place. Sleep, travel, wake, work, travel, sleep.

It’s perhaps similar to yours.

But maybe the dignity accorded is different.

The dignity of their lives

Show me how much money you have first.

The Burmese supervisor, Ko, my guide for today, takes out a 2-dollar note, then another 10-dollar note without question.

I’m surprised as the stall owner at another dorm, asks the Burmese supervisor with me today for evidence that he can pay for the items. All we took was a bottle of water, 100 Plus, and a coffee.

Do they feel proud being construction workers? Do people ever look down on them? Throughout this journey with them, I’ve been trying to find abuse, mistreatment, and disrespect.

Most Singaporeans are nice. Maybe 1 out of 100 may not. Yesterday a Mercedes Benz pulled up beside our lorry and the man told me, “Thank you! You all are our heroes! Without you, we will never build anything!”

And maybe sometimes the heroes aren’t found in the big flashy tech entrepreneurs that impact billions of lives with their inventions.

Maybe it’s found in the small, tiny, everyday actions that keep our nation humming along. The maintenance of our fibre optics, the carrying of bags of cement, and maybe even the things that we frown upon.

The times when our construction workers lie under our blocks, the times when they laugh and cheer in big groups on a Sunday afternoon in Paya Lebar, the times when they perhaps take the MRT with us, and we wrinkle our noses at the perspiration.

I’m guilty.

The small things matter so much to these workers. Like when we just arrange a lorry for them to the airport, they tell their friends about how proud they are to work for us. It’s not some fancy taxi. It’s a lorry.

As these workers move from place to place, perhaps Singapore is just another stop on their journey of life.

And we can all do small things that make that stop, a little more memorable.

Reach out with coffee, cake, or a cookie – they don’t cost much.

But to people so far from home, it means the world.

For those who want to help in any capacity, here are some organisations that are doing good things.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Homeowner Stories

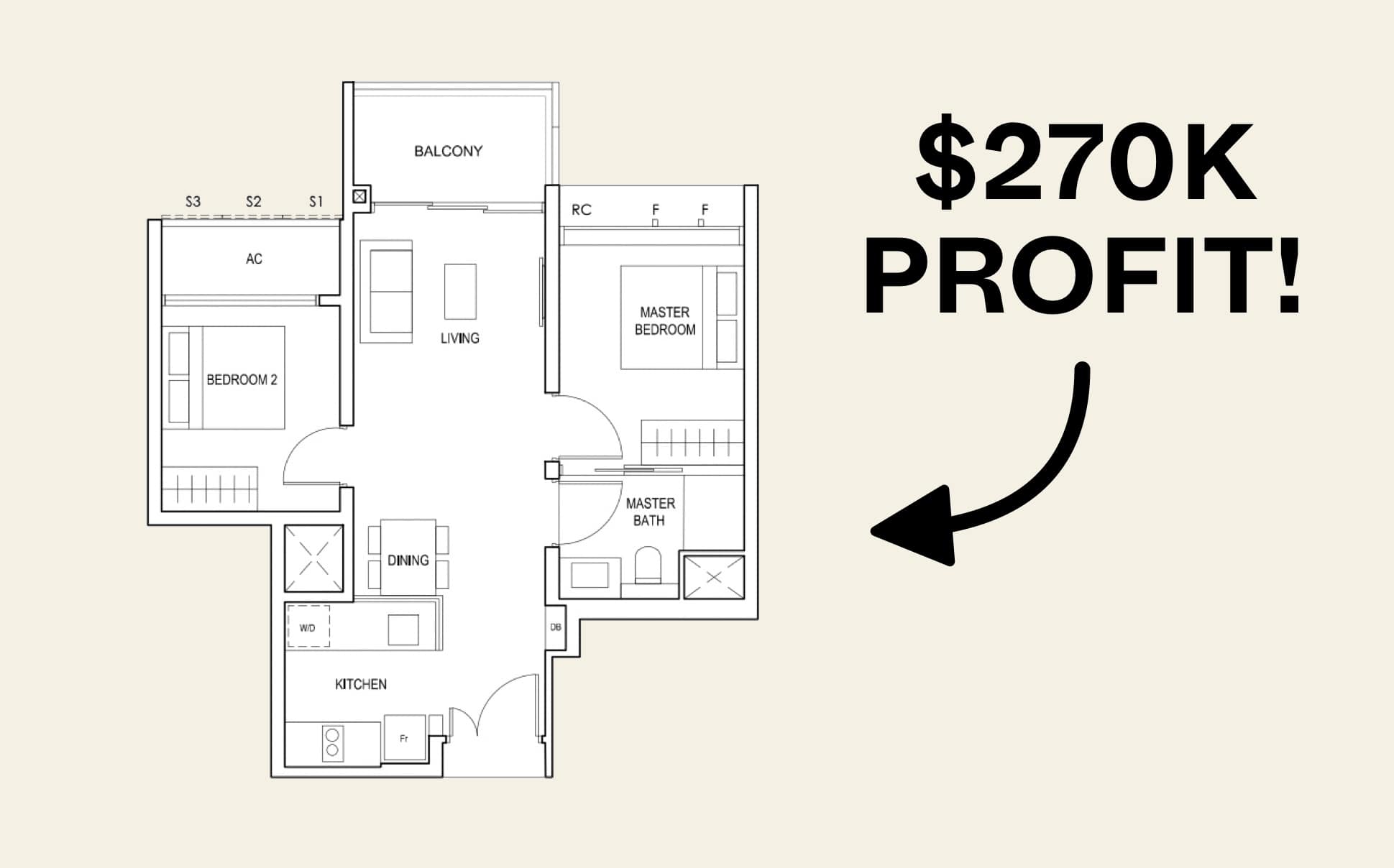

Homeowner Stories We Could Walk Away With $460,000 In Cash From Our EC. Here’s Why We Didn’t Upgrade.

Homeowner Stories What I Only Learned After My First Year Of Homeownership In Singapore

Homeowner Stories I Gave My Parents My Condo and Moved Into Their HDB — Here’s Why It Made Sense.

Homeowner Stories “I Thought I Could Wait for a Better New Launch Condo” How One Buyer’s Fear Ended Up Costing Him $358K

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News New Tampines EC Rivelle Starts From $1.588M — More Than 8,000 Visit Preview

Singapore Property News Executive Condo Prices Have Doubled In A Decade — Raising New Questions About Affordability In 2026

Singapore Property News River Modern Sells Over 90% Of Units At Launch — Here’s What Buyers Paid

3 Comments

Coming from construction related sector. It’s true, working conditions and the amount of labor work they did, doesn’t seem to be proportionate. While we are complaining about qualities of houses and furniture for the dollar we paid, how much of those actually contribute to the ground workers? (So where does majority of the money being pocketed to? Blame those who ripped you off, not those who cater your essential needs.)

TBH, first-world economy basically “squandered” the least developed, else you could ask any local here in SG, are they willing to get paid $22 per hour for such job? I’m guessing the answer is as clear as a sunny day.

Thank you for sharing their journey. We should really appreciate more the people who help build our country.