The Room That Changed the Most in Singapore Homes: What Happened to Our Kitchens?

September 29, 2025

Over the past few decades, few rooms in the Singaporean home have changed so much as the kitchen. If you revisit dusty interior design magazines under the coffee table, odds are you’ll see many of the rooms share the same concerns as today: fitting a queen-sized bed in the junior suite, feature walls for the living room, and living room novelties. The content has been repeated for years.

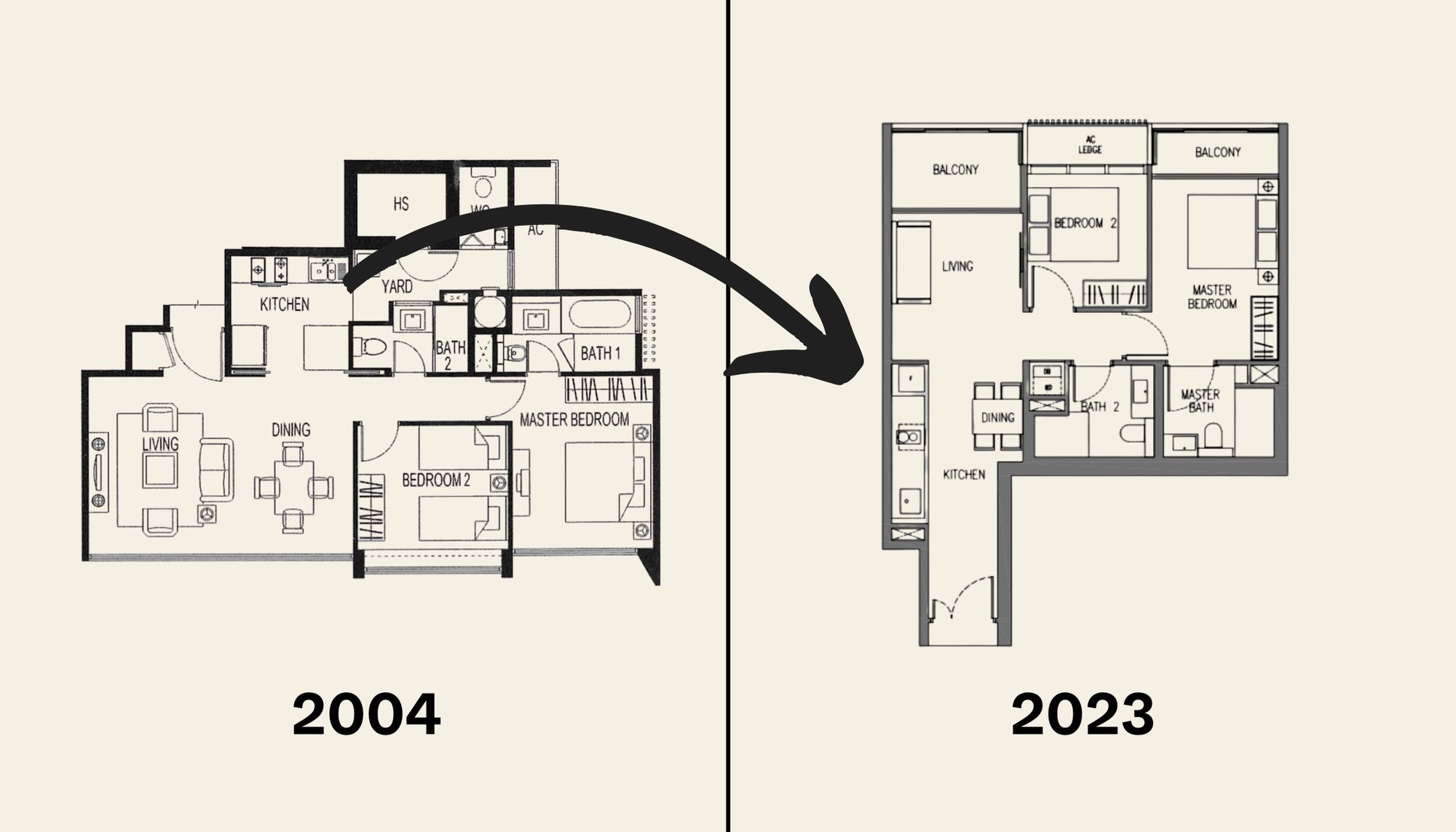

Where you might see a jarring difference though, is the kitchen. With the exception of the larger premium units, we’ve done a lot to turn this former “soul of the home” into a nook or an afterthought:

How have kitchen layouts changed over the years?

In Singapore’s early public housing and private homes, kitchens were typically separate, enclosed spaces intended for serious cooking.

In the 1950s–60s, the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) flats (predecessors to HDB) featured generously sized kitchens, with a sizable yard for both laundry and food preparation (you can see some of these old layouts here.)

These kitchens were heavily separated from living areas by walls and doors, reflecting the need to contain cooking smoke and smells. It was assumed that every family would be boiling, frying, steaming, etc. and doing so practically every day.

It was in an era where ready-made food – frozen pizza, microwavable don sets, bottled sauces, etc. – was less available. It took until about the late 1970s–80s, when supermarkets like NTUC FairPrice and Cold Storage made them the norm. And if you were going to manually grind sambal or do things with spices and onions, you wanted the kitchen to be heavily enclosed; lest eyes started watering all the way to the living room.

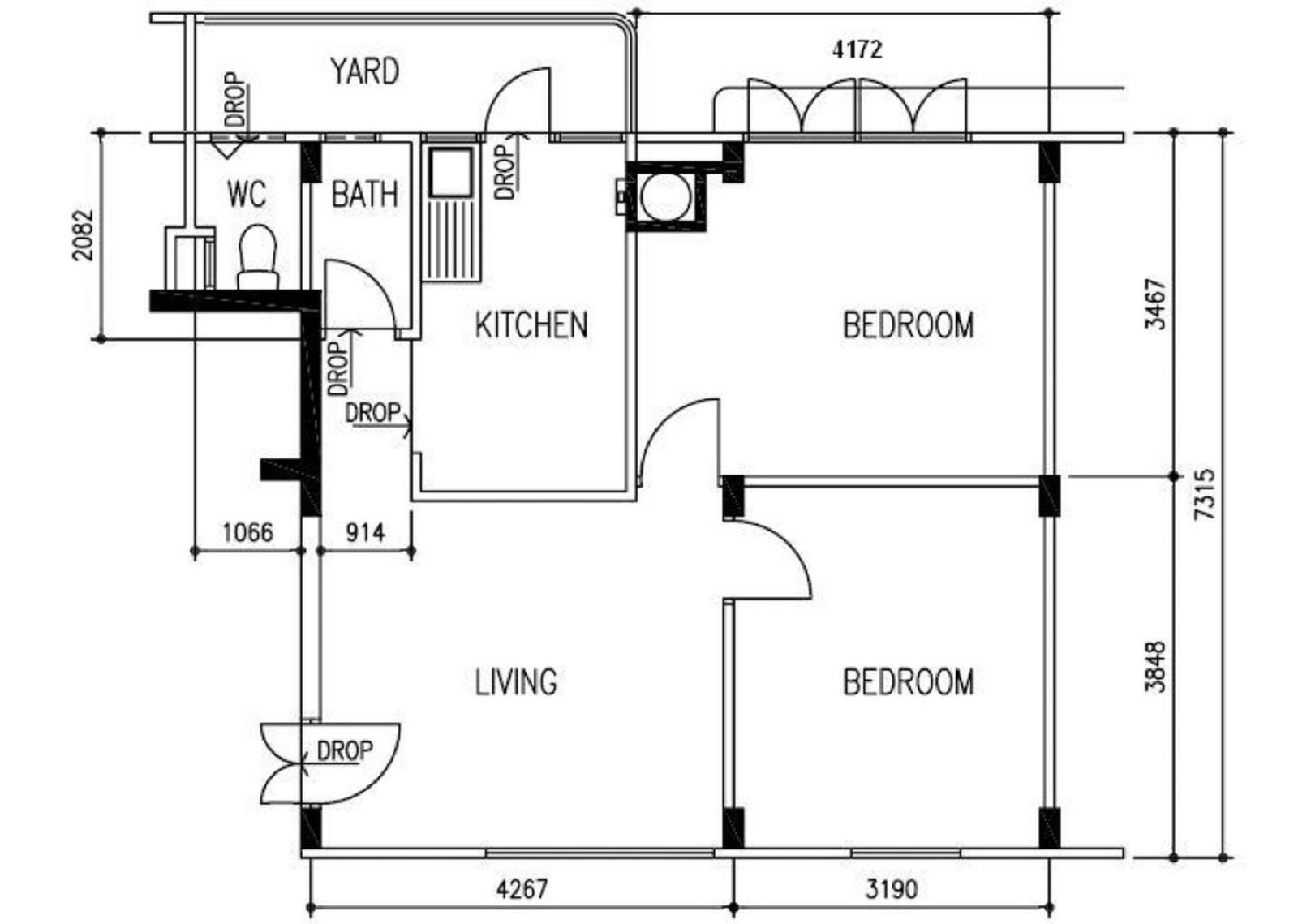

Early HDB flats of the 1960s continued this layout logic. For example, a typical 3-room flat (~646 sq ft) of that era had an enclosed kitchen at one end of the unit, with a toilet and bathing area adjacent to it. The ubiquitous – and today much detested – refuse chute in the kitchen was also considered practical (see the link above.)

These kitchens were not as aesthetic as they are today: walls were bare cement or pastel tiles, cabinets were utilitarian laminate, and there was no thought of “open shelves” or “Scandi light wood tones.”

Also, the garbage chutes, whilst expected in its day, are often considered unsightly or unhygienic today. That’s why newer flats have you bring it outside the house to a common chute.

But for all their plainness, they were soulful and practical spaces.

These were rooms that smelled of rempah being pounded, onions frying, and fish being scaled. They were designed for everyday labour, not Instagram; spaces where grandparents taught recipes, where families gathered around big pots, and where function mattered more than finish. In their very messiness and utility, these kitchens reflected the heartbeat of the household.

Ask those growing up in the ‘80s or earlier, and you’ll probably meet a lot of us who also did homework and had tuition in the kitchen, not the dining room. In fact, in many households, the kitchen was also the dining room – something that still happens today. So as plain as they were, these kitchens were also places to share, gripe, complain, or discuss family issues.

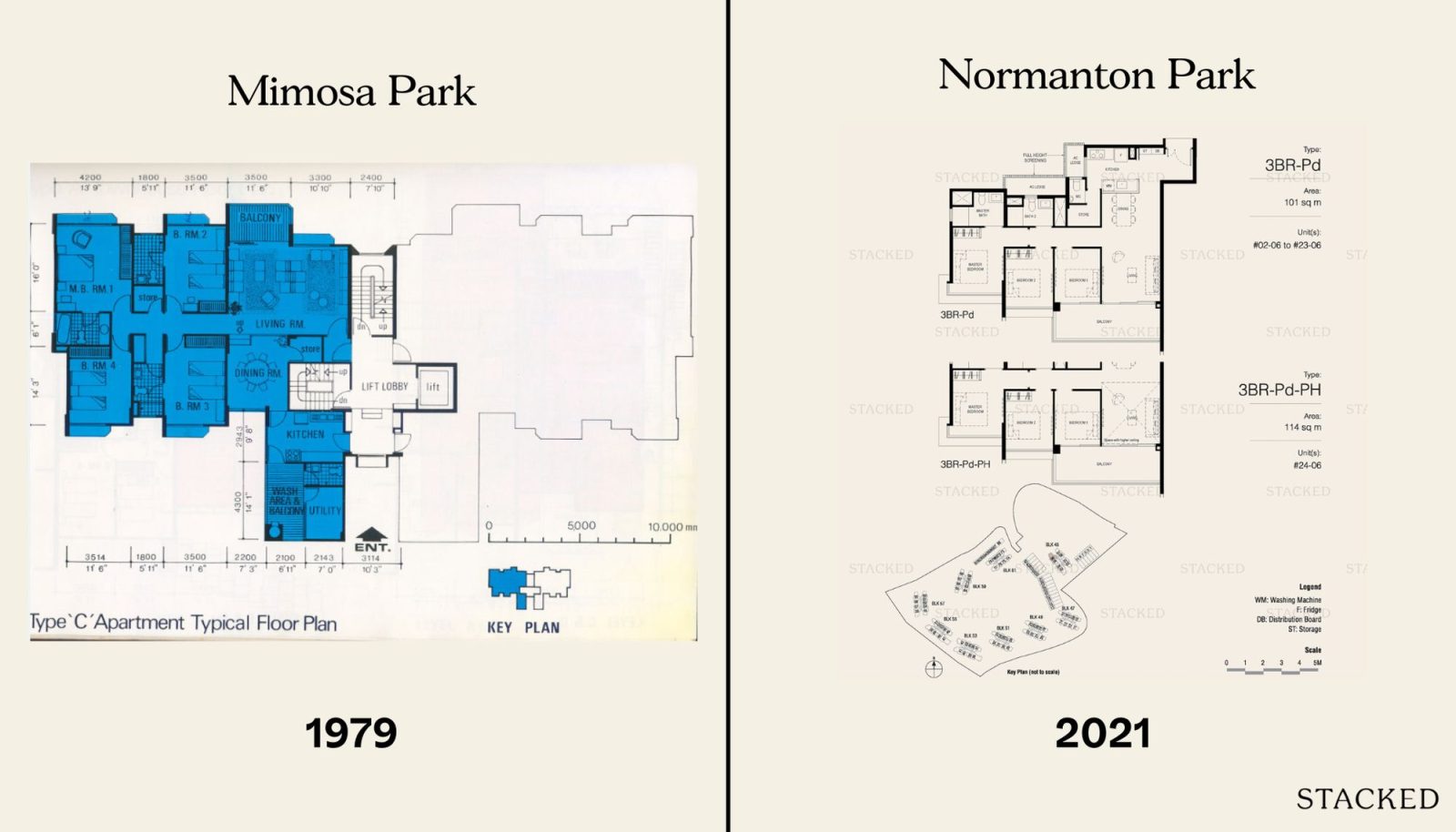

In private housing during the 1970s and 80s, a similar preference for enclosed kitchens prevailed.

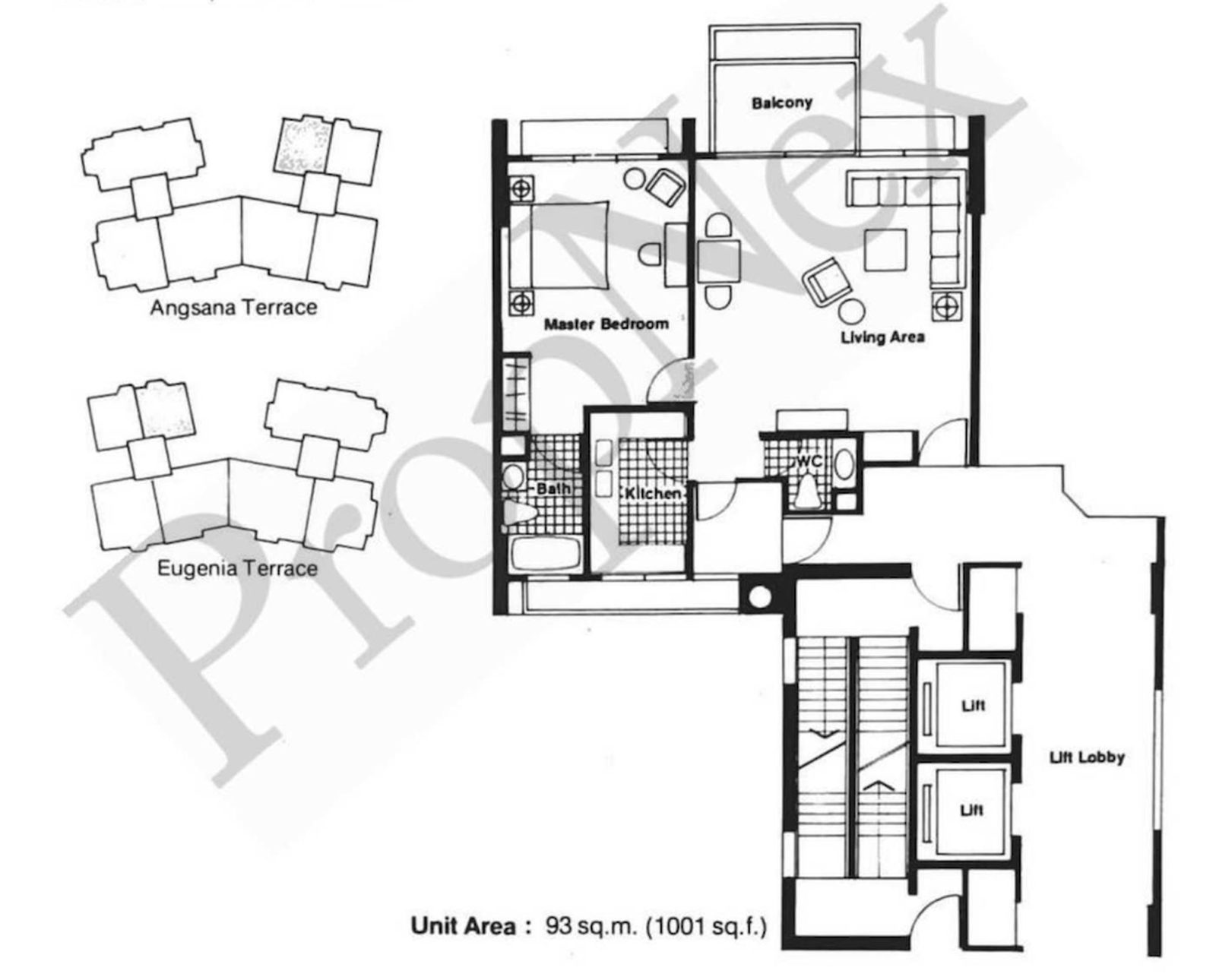

Early condominiums – which only appeared in the ‘70s with Beverly Mai – emulated the big kitchen layouts of a landed home. At the time, condos were meant to be “bungalows in the sky.” Some remnants of this still remain: if you look at Yong An Park (built 1986), you’ll see that even the one-bedders can reach 1,000+ sq ft; and even one-bedder layouts in the past still clung to the enclosed kitchen.

Tan Tong Meng Tower, a condo completed in 1977, has an equally generous kitchen with a dedicated yard, a helper’s room, and its own bathroom – underscoring how older private apartments allocated ample space for full kitchens.

In essence, whether in an HDB flat or a private residence, the kitchen of the 1960s–70s was a distinct domain meant for heavy-duty, sometimes multi-generational living.

They’re remnants of an era when grandma or grandpa were consulted when buying a home, and they’d zoom in on the kitchen – because it was assumed they’d be hanging around there to cook and dine quite often. And much like HDB flats, many children who grew up in condos or private housing in that era also saw the kitchen as a sort of family hub.

Changing Layouts in HDB Flats (1980s–2000s)

The 1980s brought about a subtle yet significant change: Supermarkets and convenience stores were spreading and becoming the new normal.

While NTUC opened its first supermarket in Toa Payoh in July 1973 (NTUC Welcome), it already had eight outlets by 1977, in areas like Tanjong Pagar, Marine Parade, and Jurong. By 1983, NTUC Welcome merged with the union-run Singapore Employees’ Co-operative (SEC) to form NTUC FairPrice – and this was a notable turning point for kitchens.

The rise of the neighbourhood supermarket meant that processed and ready-to-eat food options could reduce daily cooking marathons. At the same time, more women were also entering the workforce, and dual-income families became more common. That also meant less time in the kitchen, and more reliance on hawker food or quick meals.

HDB layouts reflected these shifts in small but telling ways.

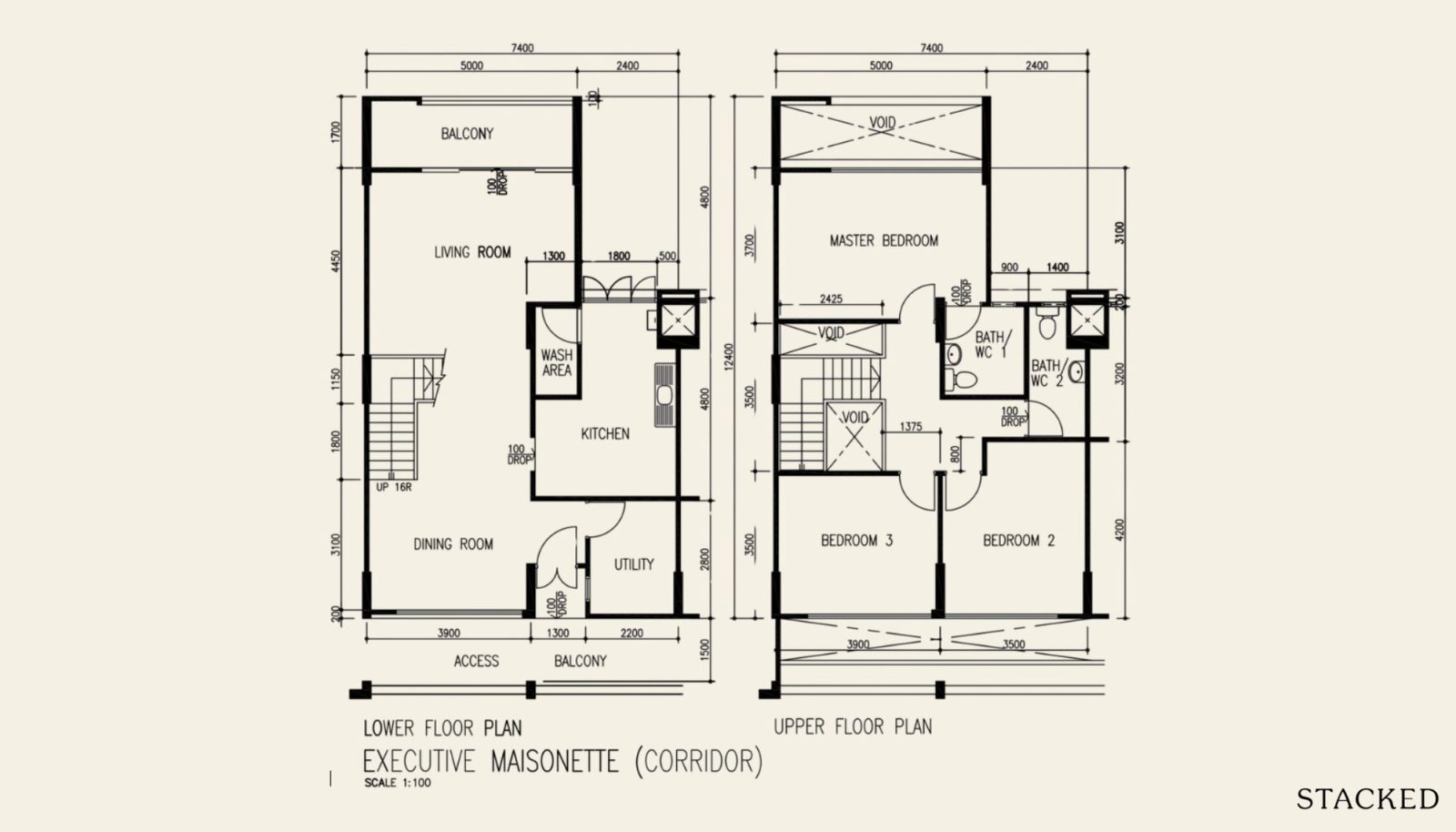

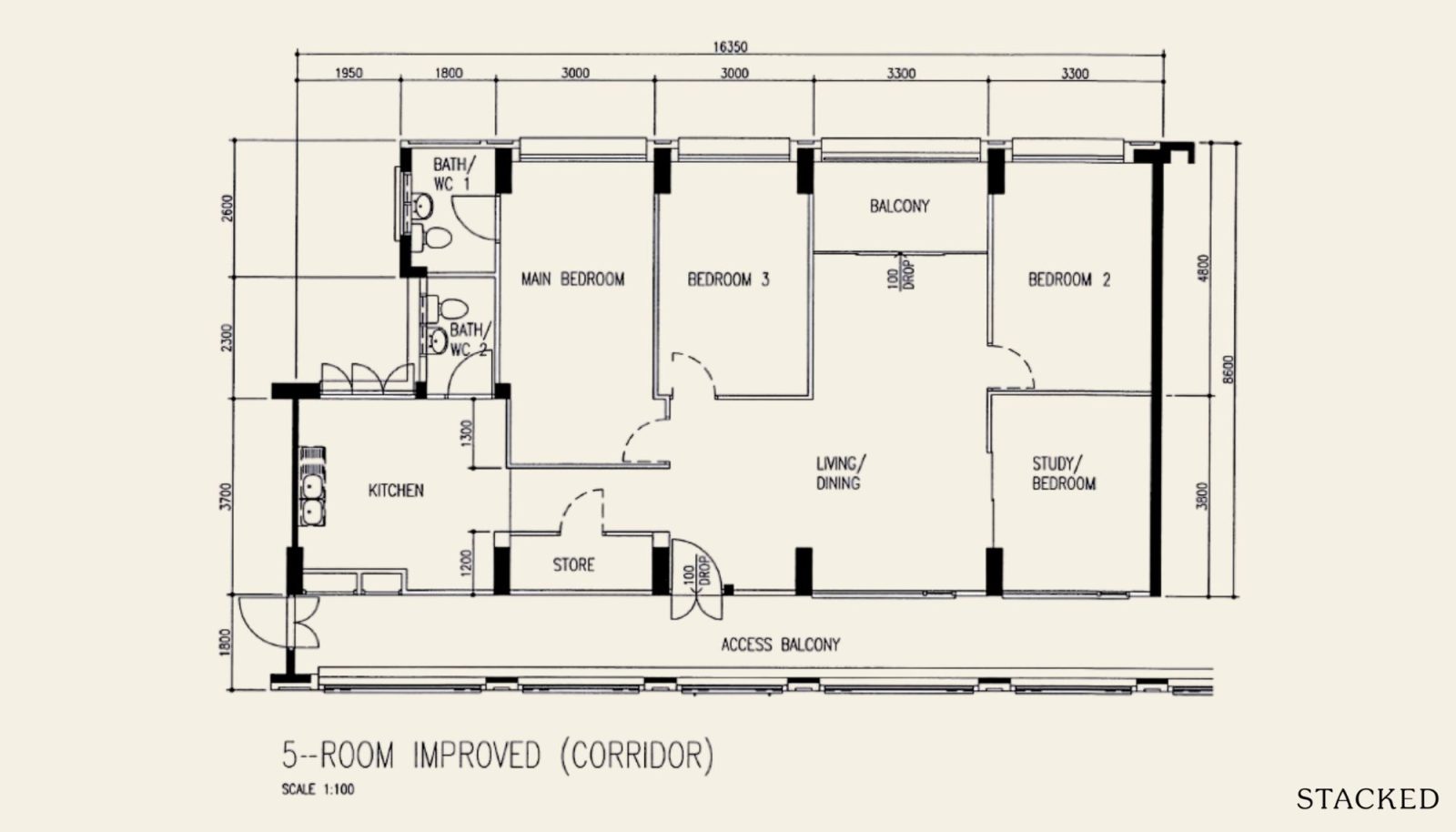

In larger flats – like the 5-room or executive maisonettes introduced in the 1980s – the kitchens were still big, but they were less central to the flat’s identity. Utility rooms or storerooms were often placed right beside the kitchen, hinting at an emphasis on storage and efficiency rather than family gathering.

By the 1990s, a new element appeared: the household shelter (bomb shelter), which usually sat near the kitchen or entrance. This chewed-up floor area that once might have expanded the kitchen or dining space. On top of that, there was a notable reduction in size for HDB flats, which also saw kitchens shrinking alongside some other rooms (although 3-room flats were interestingly spared).

Even so, through the 1990s and early 2000s, most HDB kitchens were still firmly enclosed – a conscious separation of living space from the smells and smoke of heavy Asian cooking. It’s just that by this point, it became much less comfortable for everyone to crowd around a table in the kitchen, and the rising affordability of appliances, with processed foods, meant less time standing over a stove or prep counter.

On the private housing side though, a lot of experimentation was going on; most of it reductive to the kitchen

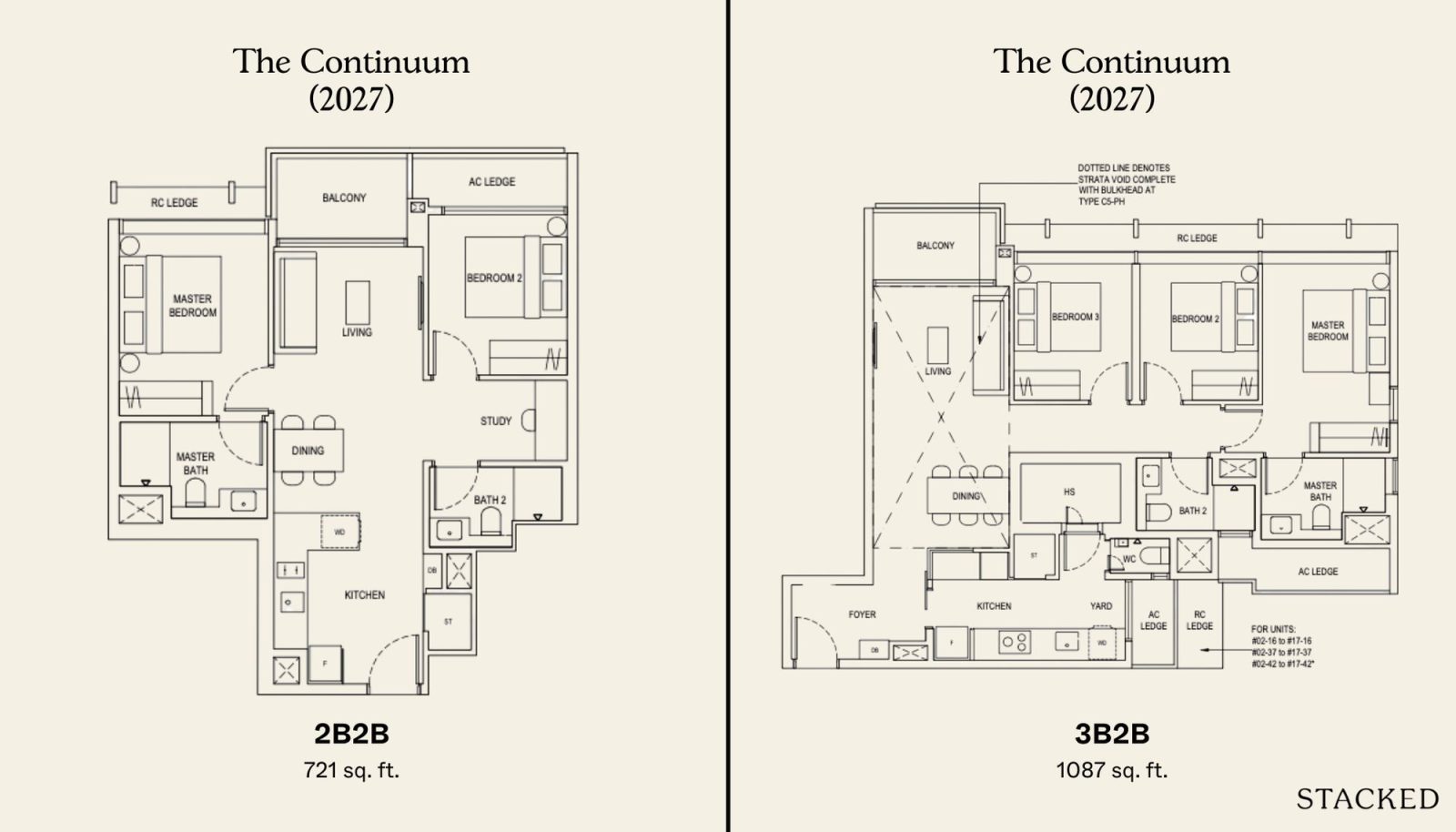

By the 1990s, private condo kitchens began to shrink in size and ambition. Developers were pressured to squeeze more units onto increasingly valuable plots, and shifted away from the sprawling “back-of-house” kitchens of the ‘70s and ‘80s. In mass-market projects, these were replaced by slim galley-style layouts: two counters flanking a narrow aisle, efficient for food prep but far less generous than before.

This suited the times, as more dual-income families meant less elaborate daily cooking, as well as more eating out. A good example comes from Signature Park (TOP 1998), where one two-bedder’s original micro-kitchen was described by its owners as “cramped and stuffy, with very little working space.”

Their eventual renovation – which we covered here – had to knock down part of the wall to integrate it with the dining area; and we daresay theirs was a common issue in ‘90s and early ‘00s kitchens.

This trend marked the decline of the traditional kitchen, especially in compact units (for smaller one and two-bedders, a kitchenette sometimes replaced the kitchen altogether).

The kitchen was on its way to becoming a functional necessity, rather than a space for cooking rituals or social interaction.

The rise of the open-kitchen

By the 2000s, we also began to see the first signs of open-concept layouts in public housing, though not yet mainstream. In 2012, HDB piloted an Optional Component Scheme (OCS) offering buyers the choice to have an open kitchen layout (i.e. forgoing a partition wall) in a new BTO project – this was at Teck Ghee Parkview.

This proved popular, and HDB alleged that from 2012 to 2017, about 70 per cent of buyers opted for the open kitchen when given the choice

Given this strong demand, HDB officially announced that starting February 2018, all new BTO flats would come with an open kitchen concept by default (where the layout permits.

This policy marked a significant turning point – after decades of strictly enclosed kitchens, the open-concept kitchen became the new norm in public housing.

From discussions with contractors and realtors, there’s a claim that the open kitchen concept started in private housing. From the late 1990s onward, Scandinavian design filtered into Singapore’s showflats; mostly accompanied by “Japandi” and “Mujicore” minimalism. The palette of light timber, white surfaces, and clean lines dovetailed perfectly with the open-concept ideal: the kitchen was reimagined less as a workspace than as furniture that blended into the living area.

Now here’s the interesting bit: the open kitchen is a very family-oriented design.

One of the main reasons it caught on in the West is that it allows parents to cook while keeping an eye on their children in the living or dining area. The kitchen, dining table, and living room are collapsed into one visual field, which means dinner prep doesn’t cut parents off from family life.

In fact, much of the Western marketing for open-plan homes in the 1970s–90s leaned on this imagery: mothers preparing meals while children did homework at the island, or couples socialising across the counter.

Now locally, this idea bumps into a practical obstacle: Asian cooking doesn’t suit an open kitchen. But this aside though, the open kitchen’s family logic does make sense.

It also means that, despite being family-oriented, the open kitchen actually works against the soul of the room.

The open kitchen attempts to dissolve the kitchen into other spaces, instead of preserving it as its own family area. The old kitchen, whether in a kampong house or an early HDB flat, was a room with boundaries: smoke and noise stayed inside, but so did the intimacy. The kitchen’s walls gave it focus: a stage for everyday rituals.

The open-concept kitchen, by contrast, makes the kitchen a backdrop. It is absorbed into the living/dining area’s aesthetic, forced to look tidy and decorative, rather than a room to get messy in.

In trying to make the kitchen “social,” the open concept ironically strips it of its own identity – no longer a place to retreat, congregate, and work together, but part of the living/dining zone that’s really more of a show space.

But is the soulful kitchen coming back quietly?

If the 1990s and 2000s saw the kitchen dissolve into a decorative backdrop, the pendulum may be swinging back.

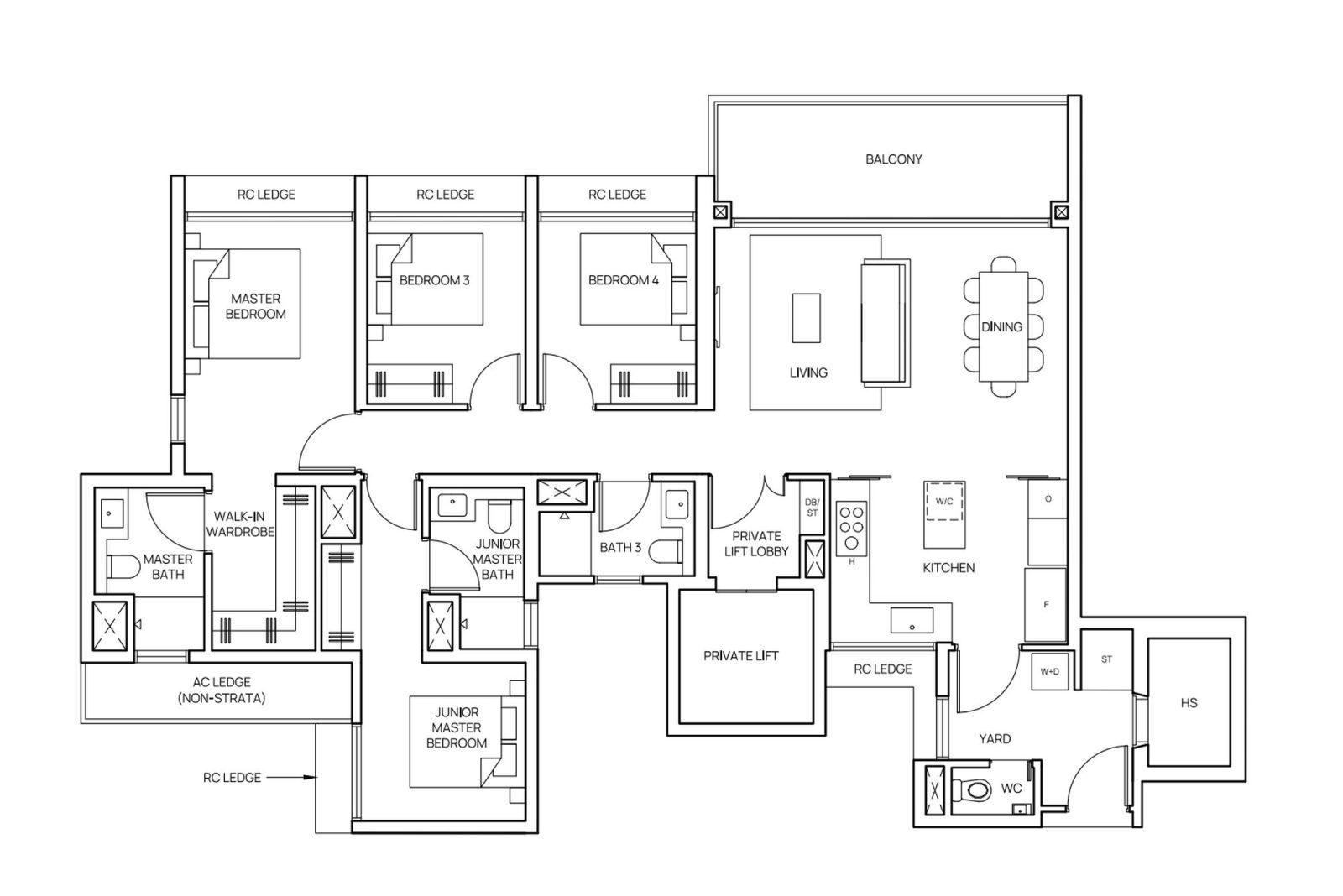

In larger condo units, developers have brought in the dual kitchen: a dry island fronting guests, and a hidden wet zone where the wok can breathe. Projects like Canberra Crescent Residences and Skye at Holland have kitchens like these in larger units.

Note that the availability of the format is irrelevant to whether the condo is in a prime area or not – it’s about the size of the unit. While the wet and dry layouts offer a best-of-both-worlds scenario, they’re often in large, high-quantum units beyond the affordability of many Singaporeans.

On the public side of things, HDB seems to be revisiting the enclosed kitchen. At the MyNiceHome Gallery, both the new 4/5-room and the smaller 2/3-room flats are still designed with the option to fully enclose the kitchen, often with a dedicated service yard tacked on. While open-concept styling is showcased, the “bones” of the flat always allow for a return to traditional forms.

We don’t know if the soul of the kitchen will actually come back

This goes way beyond unit layouts and architecture, and it’s also a matter of lifestyle and culture.

In kampong houses or early HDB flats, the kitchen was the family’s heartbeat – noisy, messy, but intimate, where daily life unfolded in full. Today we have smaller households, busier schedules, and, to be blunt, a lack of skill.

(Do I really want a wet kitchen, if I know my attempts to use a wok will only result in an SCDF visit?)

Architecture can make space, but only culture and lifestyle can give it meaning. But who knows – maybe the high cost of eating out, plus all the Master Chef shows, will help nudge us back into the kitchen, and that would do more to bring back its soul than a high quantum layout.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

How have kitchen layouts in Singapore homes changed over the years?

Why did kitchens in Singapore homes used to be separate and enclosed?

What led to the shrinking of kitchens in Singapore public housing from the 1980s onwards?

When did open-concept kitchens become common in Singapore public housing?

Are traditional, soulful kitchens making a comeback in Singapore?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Trends

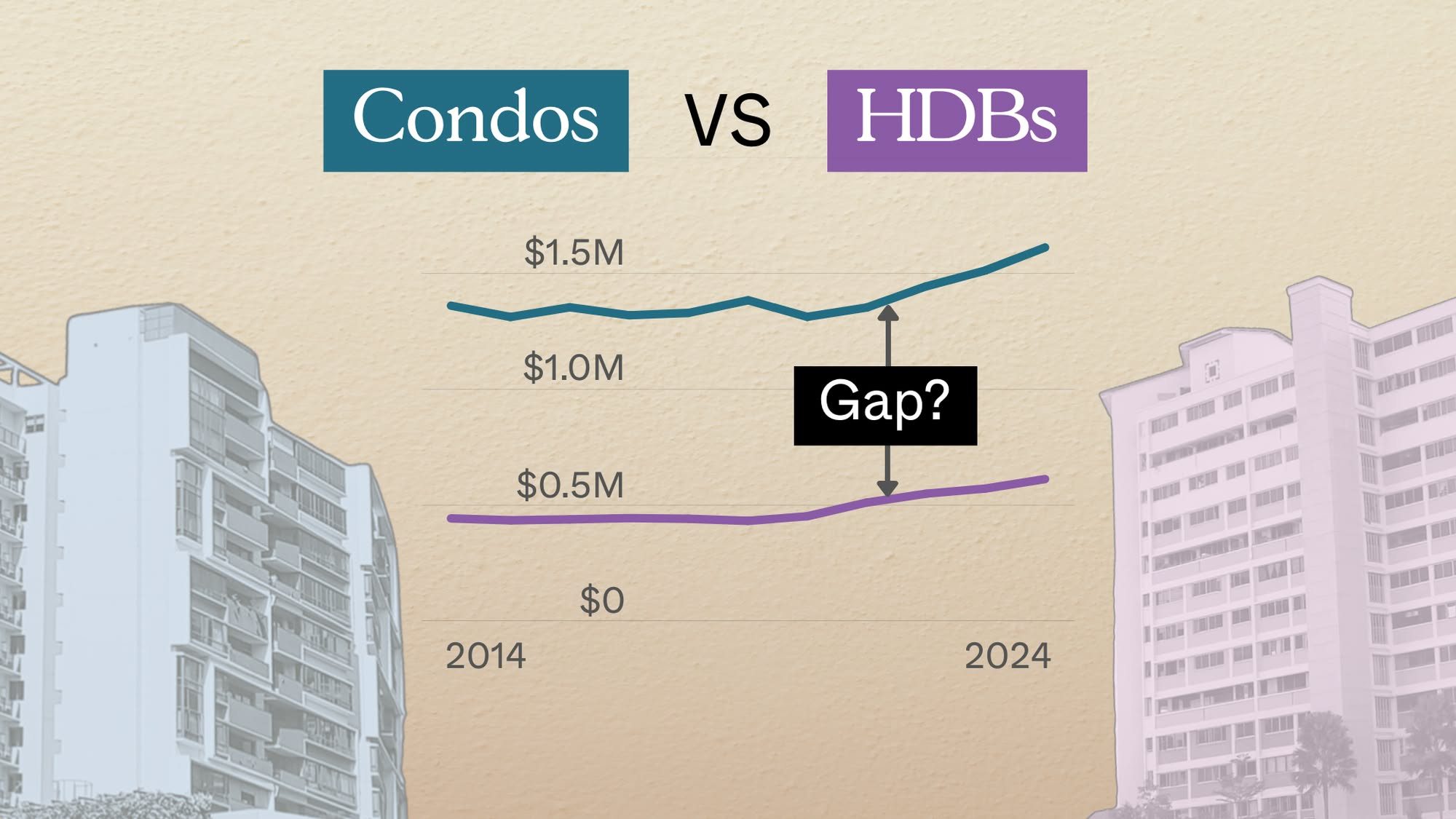

Property Trends Condo vs HDB: The Estates With the Smallest (and Widest) Price Gaps

Property Trends Why Upgrading From An HDB Is Harder (And Riskier) Than It Was Since Covid

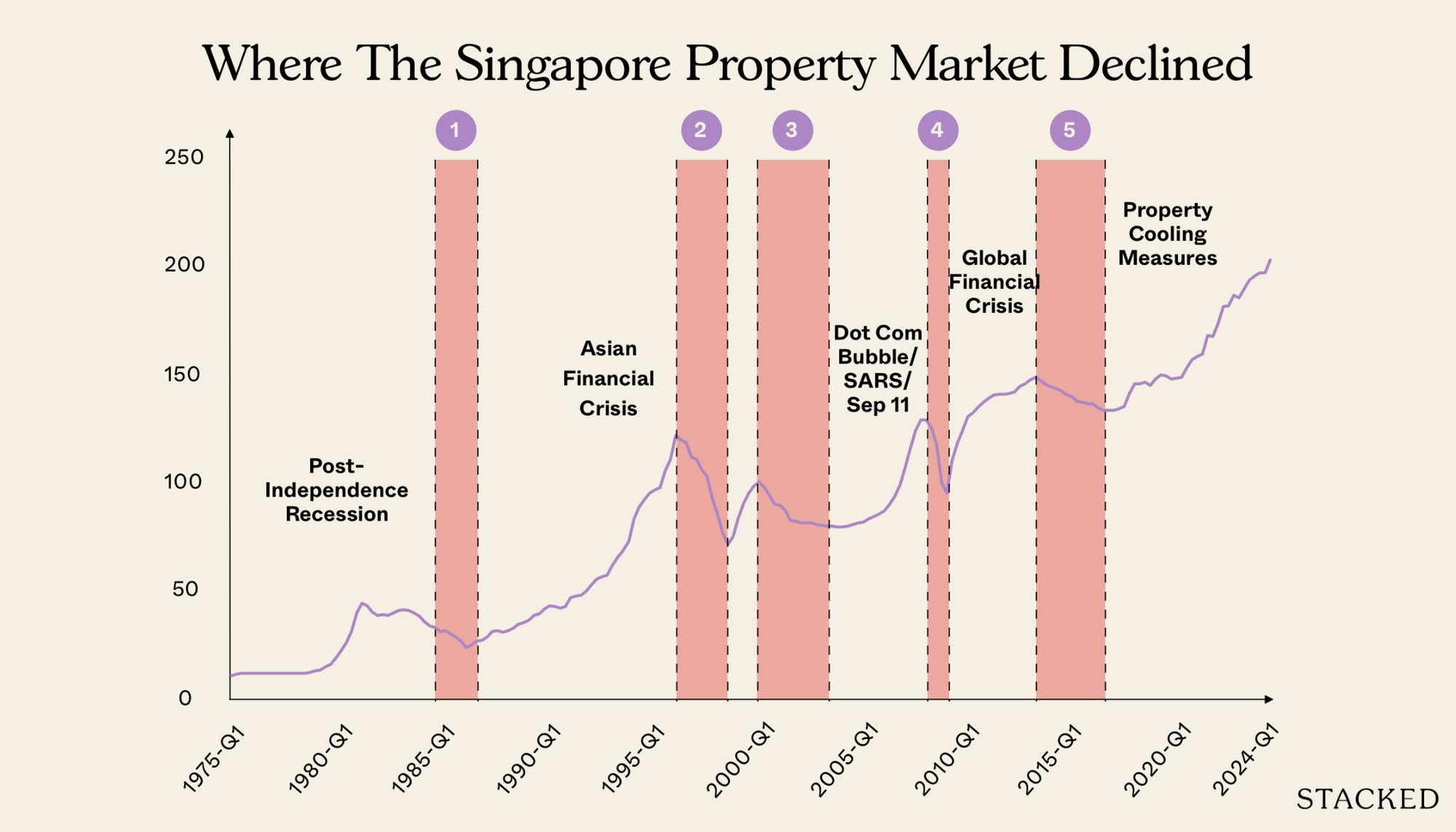

Property Trends Should You Wait For The Property Market To Dip? Here’s What Past Price Crashes In Singapore Show

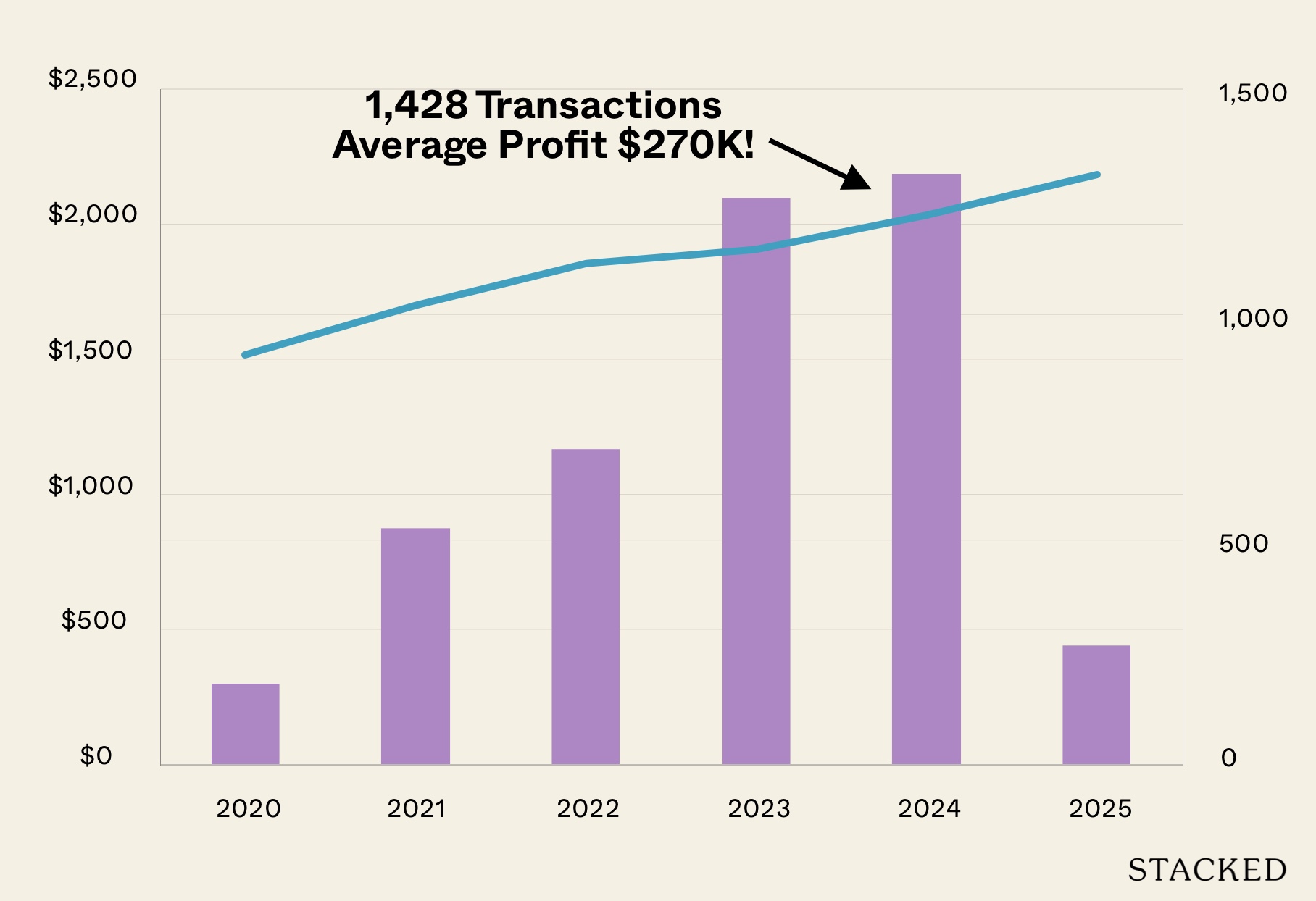

Editor's Pick Condo Profits Averaged $270K In 2024 Sub Sales: Could This Grow In 2025?

Latest Posts

New Launch Condo Reviews River Modern Condo Review: A River-facing New Launch with Direct Access to Great World MRT Station

On The Market Here Are The Cheapest 5-Room HDB Flats Near An MRT You Can Still Buy From $550K

On The Market A 40-Year-Old Prime District 10 Condo Is Back On The Market — As Ultra-Luxury Prices In Singapore Hit New Highs

1 Comments

even if you’re gonna use chatgpt to write the article, at least remember to replace the links with actual ones.