Japan Vs Singapore: Why Japan’s Zoning Laws Make Sense And What We Can Learn

March 16, 2022

It’s no surprise that space constraints are a major factor in Singapore. However, Japan – while admittedly bigger – often has the same issues, with most of the country consisting of islands. And as Singapore’s population grows, and we seek to decentralise, our zoning laws will have to change. Perhaps there’s something we can pick up from our not-so-far-away neighbours:

How does our urban zoning work?

In Singapore, zoning laws tend to be fairly strict and well-defined. We have about 31 types, as you can see here.

Notice that the categories are very specific. For example, even Residential with 1st Storey Commercial is separate from just Residential; while Business zones can be Business Park, Business Park (White), B1 and B2, and so forth.

While appeals can be made, URA is quite strict with the zoning. It’s mostly futile to request turning your landed home into a shop, or to try and build a house on a plot zoned for other commercial interests.

This stems from Singapore’s early days, when this sort of close management was vital. Our initial urban planning was insufficient; so much so that in 1962, the United Nations had to help us formulate the State and City Planning Project (SCP) to ensure proper housing and support employment.

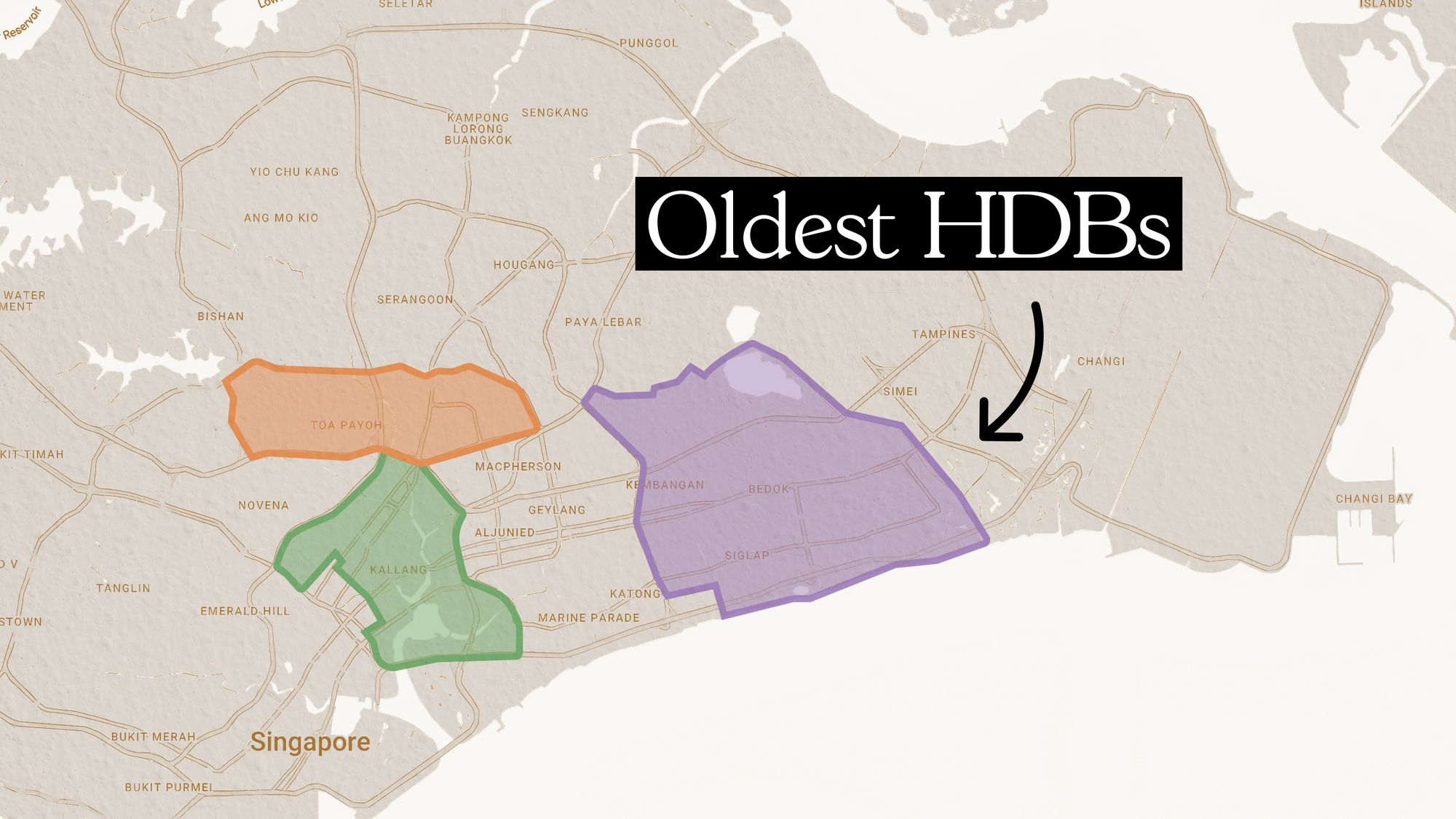

Many parts of Singapore were a sprawling mess before that, which also made public transport and work a major headache (ask your grandparents – many might remember hour-long walks to work being common in some areas).

The SCP for 1971 set the tone for subsequent master plans, for decades to come. It established the concept of tightly regulated residential, industrial, and commercial zones, all forming a ring around the central water catchment area. This made sense at the time, given the population numbers and road networks.

But that was a plan for a smaller population, in a different age

URA has evolved with the times, and today’s Master Plan is a lot more flexible. One of the new objectives we have is gradual decentralisation.

To oversimplify a little: we don’t want to concentrate all the major commercial interests or amenities in one place (e.g., the CBD and Orchard). Doing so disincentivises homes in fringe regions like Changi, Jurong, Woodlands, etc.

On top of that, our transport infrastructure can’t really handle it (both public and private). It’s bad enough now with everyone crowding in and out of the CBD at rush hour – imagine it in a decade, when the population goes up.

However, this sort of decentralisation means even far-flung neighbourhoods should form hubs or enclaves of their own: residents should have major malls, workplaces, schools, etc. nearby, so they don’t need to travel too far out of their neighbourhood.

This is where taking a cue from Japan might come in handy.

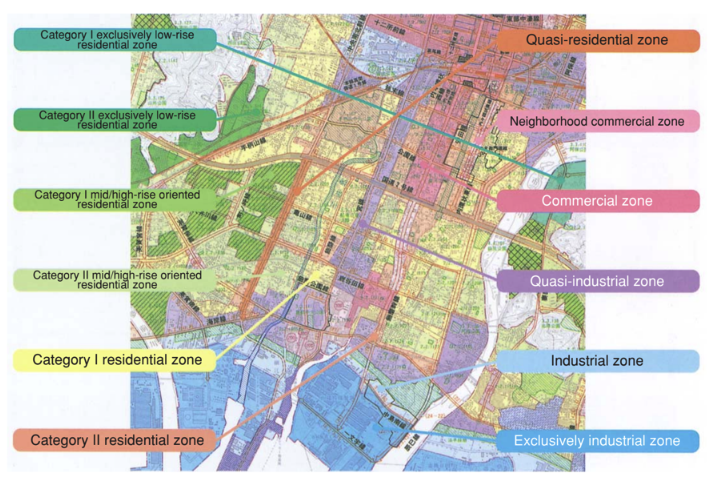

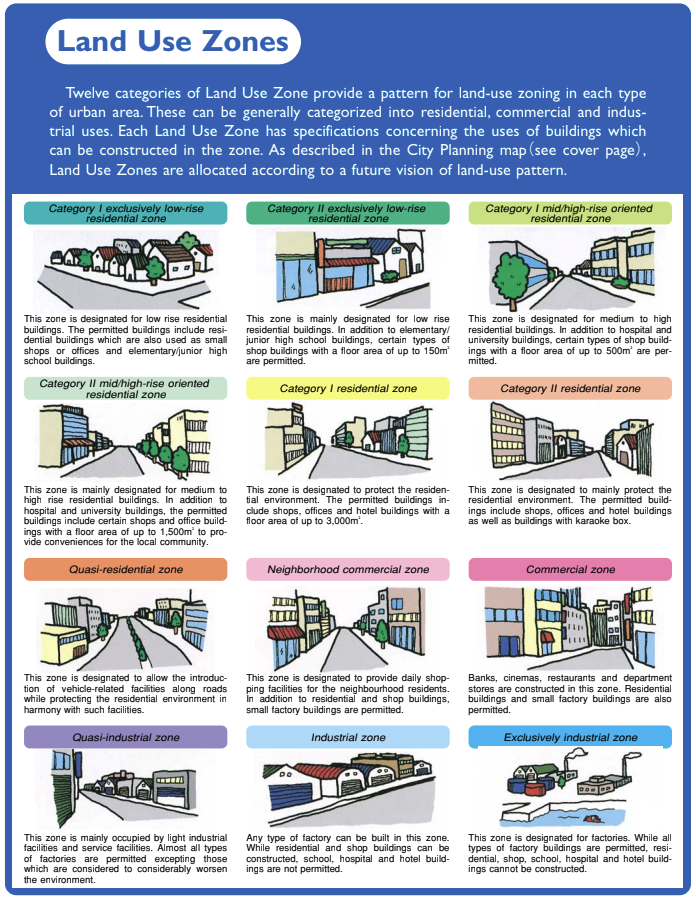

Japan’s urban planning offers a higher degree of flexibility

Japan only has 12 different zones, with broad similarities to what we see in Singapore. The key difference, however, is that Japan allows for maximum-use of certain developments, rather than tightly controlling what gets built. Even the most strict zone can allow for home-based businesses and small local shops. For example:

A low-density zone might allow for a maximum number of stores and schools, based on the likely level of noise pollution/traffic. This could mean, for instance, the area can hold purely residential units, or residential units and two stores, or residential units and a school, etc.

A higher-density zone, even though it’s zoned residential, might have a higher tolerance for more shops, schools, or other commercial interests. Again, this doesn’t mean the government will force the construction of these things – it may well end up being purely residential anyway.

Here’s a great video to watch on the Japanese zoning laws. If you watch from minute 4.55 onwards, you’d see that in what is classified as an Industrial Zone, it looks like a purely residential one from that flexibility.

However, by setting “maximum use” based on disamenity (i.e., nuisance like noise), it allows for neighbourhoods to develop in a much more organic way. It allows for amenities that are not too disruptive – such as a minimart or clinic – to spring up anywhere. And in practice, urban planners aren’t so precise as to correctly determine an exact corner of the neighbourhood really could do with, say, a dental clinic or a small grocer.

More from Stacked

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

Will 1 Canberra, The Warren, Or A Small Freehold Condo In Potong Pasir Be A Better Choice For A Family Of 4?

Hi stacked homes,

This also promotes more free-market development. For example, if some amenities are needed within a residential area, developers are free to buy over the space from residents and put up commercial properties (insofar as they meet the maximum limits, and hence don’t become too much of a nuisance). Right now in Singapore, this can’t happen without a zoning change; and so our urban planners have to micromanage these things to an incredible degree.

Overseas Property Investing7 Mythbusters Of Buying Overseas Property: Clarifying The Basic Risks

by Ryan J. OngIt’s ideal for decentralisation and mixed neighbourhoods

Because Japan doesn’t impose one specific type of development for a zone, mixed-use is part and parcel of the equation.

For example, if an area is zoned for a large office building, a certain maximum amount of space can be taken up by the office – the remaining space has to be given over to other uses, such as residential.

This prevents the creation of land plots that are purely given over to one purpose. This complements the overall drive toward decentralisation, as it ensures each individual neighbourhood has its own mix of shops, offices, and residences.

Right now, Singapore has decentralised by creating new business hubs – such as Paya Lebar Quarter, Changi Business Park, One-North, etc. These already follow the overall theme of mixed-use developments anyway, blending retail, work, and residential (what developers like to call a Work-Live-Play concept).

A change to a more flexible zoning system would match the intent, while removing the need for our urban planners to dictate – via some crystal ball – exactly how much space should be for shops, how much should be offices, and how much should be homes.

In Japan, “residential” is not painfully specific

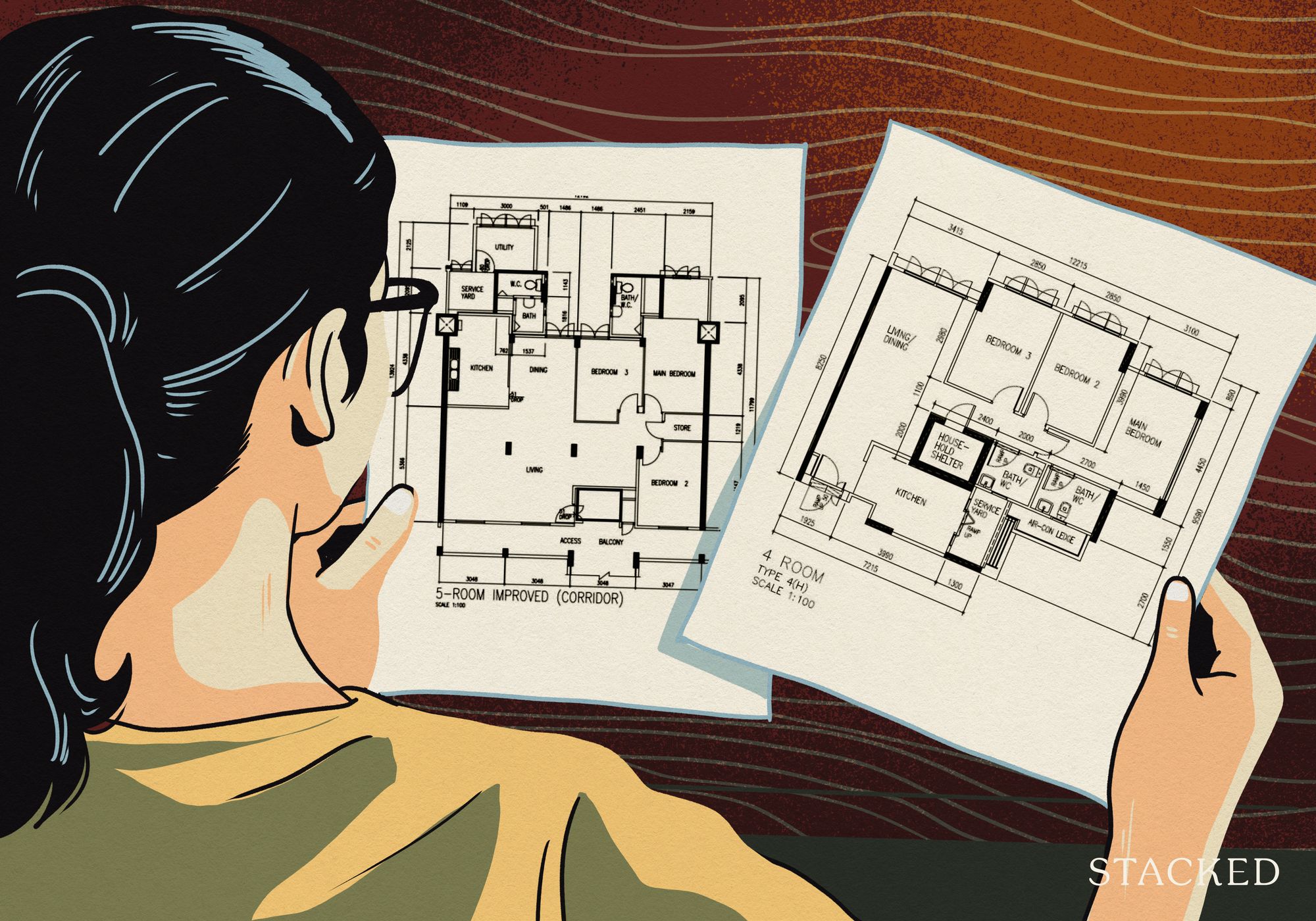

Japan doesn’t control whether the residences built are detached houses, condominium complexes, apartments, etc. Residential refers to any mix of these.

While the concept is a bit shocking to Singaporeans (we like neat definitions of landed enclaves vs. flats vs. condos), it has certain benefits. It could, for instance, see neighbourhoods reconfigure themselves into apartments to deal with a denser population there; or spread out into more landed homes or boutique condos, as the population thins out.

This could help to mitigate (although not totally remove) the entrenchment of certain areas as being purely affluent landed housing, or from turning into a lot of vacant apartments and flats if – at some point in future – the population thins out.

That said, we shouldn’t go all the way in that direction either

Some home buyers may not be too happy about a minimart opening next door; or even worse, a higher-rise building appearing to block their view. The flexibility does make planning a bit harder on buyers, as they become less clear on what might surround their property in the future.

But this opens up a whole other discussion, on whether the government is obliged to consider such interests. The priority of bodies like URA is, after all, the well-being of the whole city; not the capital appreciation of a given property.

For more on the Singapore real estate market, as well as new ideas and trends in property, follow us on Stacked. We’ll also provide you with in-depth reviews of new and resale properties alike.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

How do Singapore's zoning laws compare to Japan's in terms of flexibility?

What is the main benefit of Japan's more flexible zoning system?

How does Japan's zoning approach support mixed-use neighborhoods?

Why might Singapore consider adopting a more flexible zoning system like Japan's?

What are some potential drawbacks of adopting Japan's flexible zoning approach in Singapore?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

On The Market A Rare Freehold Conserved Terrace In Cairnhill Is Up For Sale At $16M

Singapore Property News This Tampines EC Will Preview on Friday — It Is One of Two New ECs in the East in 2026

Property Investment Insights This 55-Acre English Estate Owned By A Rolling Stones Legend Is On Sale — For Less Than You Might Expect

2 Comments

I feel that although Town Planning in Japan gives more flexibility, it is messy. I still prefer Singapore’s MP although stricter.