5 Ways Housing Shapes Singapore’s National Identity

August 9, 2025

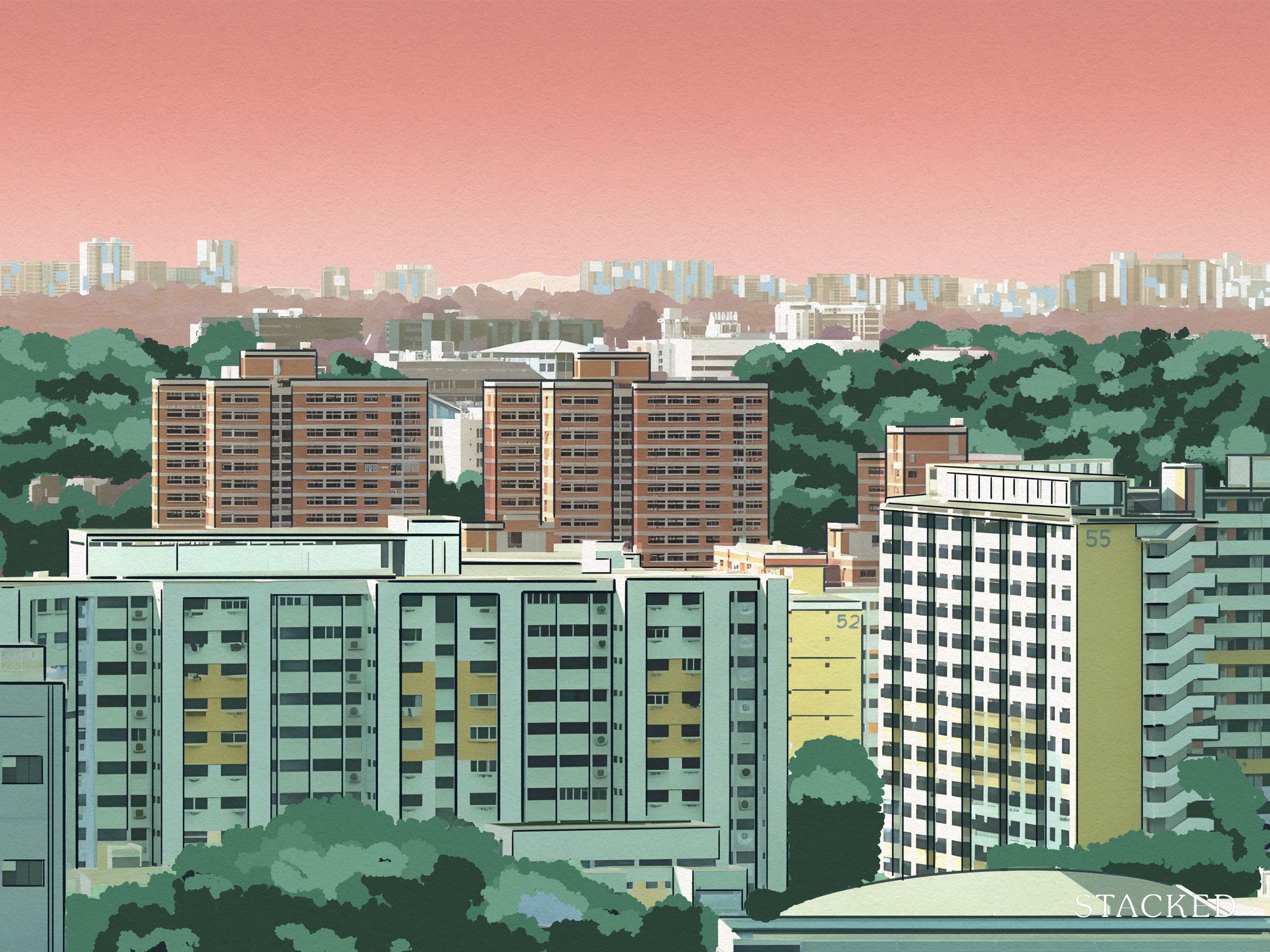

As SG60 approaches, it’s a good time to consider how Singapore’s housing story is inseparable from its national story. Housing is one of the qualities that makes Singapore stand out among many countries – whilst most states struggle with the issue of affordable housing, we have a home ownership rate of close to 90 per cent.

But the kind of housing that allows that is more than just real estate: it’s a social compact, a cultural backbone, and yes, a source of heated debate. The physical built environment, as well as the socioeconomic connotations of what type of home you own, are all an indelible part of the Singaporean identity. Here are five ways in which our housing defines a big part of who we are:

1. Housing built the nation, literally and figuratively

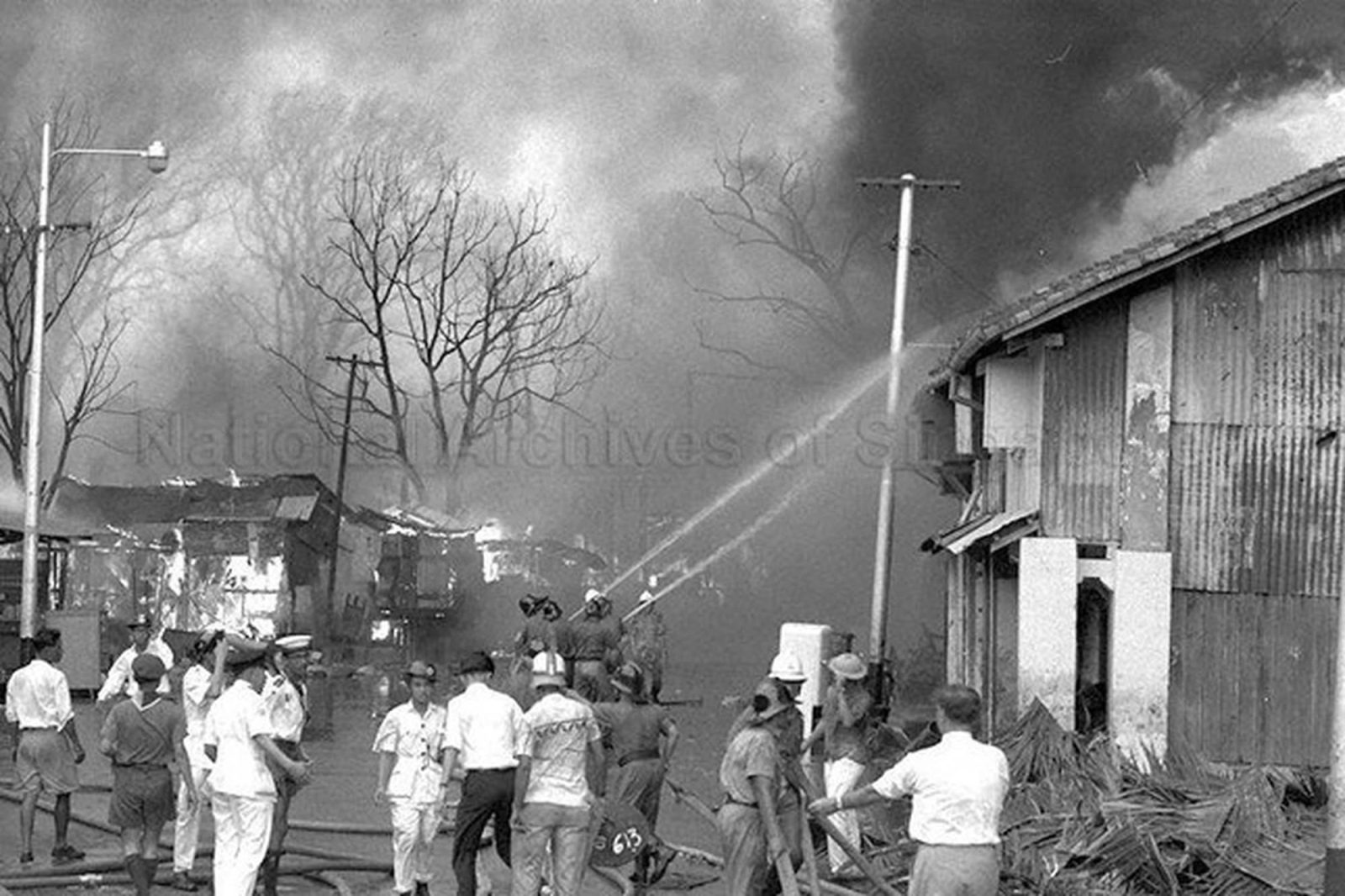

One of our defining post-Independence moments was dealing with our housing crisis. A turning point was the 1961 Bukit Ho Swee fire, which destroyed the homes of around 16,000 people, and exposed the problems of so many people crowding into non-standardised housing (i.e., something with a zinc roof, built by an uncle who’s “qualified” because he owns a whole hammer from London).

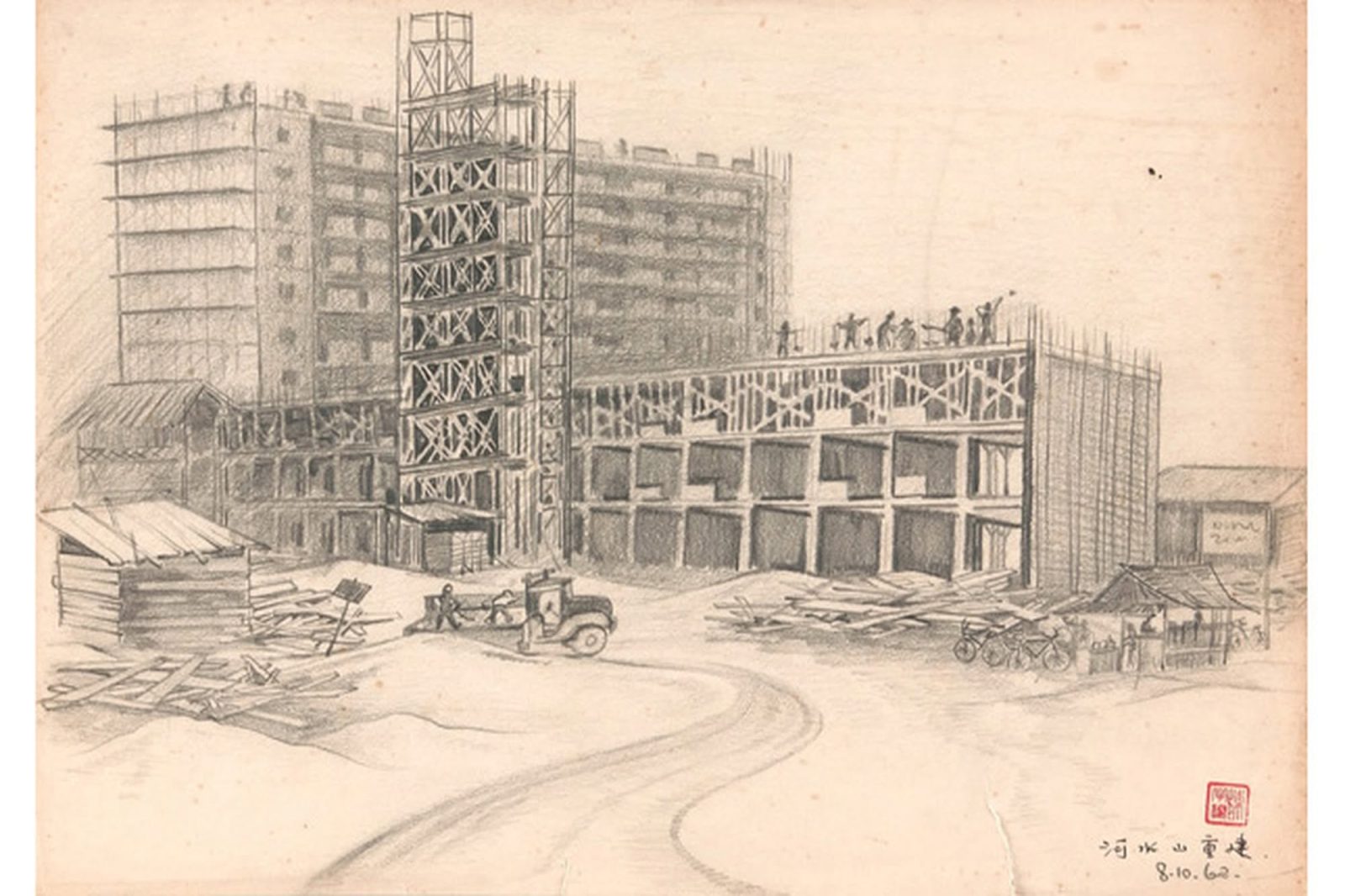

Although the fire was a crisis situation, it ironically gave us the confidence we needed to come to today’s built environment. The newly established Housing & Development Board (HDB) was established in 1960 and, in less than five years, HDB built over 54,000 flats.

Prior to this, the benchmark set by its predecessor – the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) had only managed 23,000 homes over a period of around 32 years. That’s about 719 units per year, versus HDB’s 10,800 per year; so no wonder they got fired.

Anyway, HDB proved that we could do what was needed. Its first flats, although basic, provided then-modern amenities like piped water and electricity, thus laying the building blocks of Singapore today. Each finished block was a tangible sign of progress that Singapore was growing beyond a tropical slum.

Just as critically, the Singapore government realised that the best way to get people to really commit to this country is to let us be homeowners. In 1964, the government introduced the Home Ownership for the People scheme, allowing citizens to buy their HDB flats at subsidised prices.

This was quite revolutionary, since in most countries – all the way till today – public housing is almost always viewed as some kind of charity-based rental scheme. We could ask if, had the government not pushed for high home ownership, Singaporeans would still be happy to make subsequent contributions like serving NS, or give the government so much leeway to take over land when needed.

Today, over one million HDB flats house about 80 per cent of Singapore residents, and about 90 per cent of resident households own their homes – one of the highest homeownership rates in the world. Even private property is indirectly built on the back of HDB: the majority of condo buyers today are HDB upgraders, whose HDB flat provided the sale proceeds needed to move into a private home. So an HDB flat is, arguably*, a tool for social mobility.

The physical nation was constructed in brick and mortar, right alongside the metaphorical commitment to build a nation.

*I say arguably because I acknowledge it’s not entirely free from debate. I’m sure many feel that HDB flats should not be used in this way, that the promises have changed over time, or that the system may even contribute to certain inequalities.

2. In Singapore, where you live is often who you are (for good or for ill)

The truth is, we make a lot of assumptions about our fellow Singaporeans based on where they live. Even if we’re polite enough to repress it, we know that living in a landed home, versus a condo or a flat, speaks volumes about our background or situation in life. Even certain government benefits are tied to your address, as it’s assumed that residents of certain property types will need less help.

Perhaps the best-known term that’s arisen from this is “heartlander.” Purely from personal experience, I feel this term came about in the 1990s, as I never heard it when I was a child in the ‘80s.

I suspect it’s because the correlation between housing segments and social class was less defined in earlier decades. The first condo only came about in 1974 (Beverly Mai, which today is Tomlinson Heights). And prior to the 1970s, it wasn’t always true that landed homes meant wealth. Some older landed houses were rudimentary and affordable, occupied by lower-income families. It was only with rising land values that these homes became associated with wealth and status.

But by the ‘90s, the term heartlander was definitely in the newspapers, on the radio waves, and on TV. “Heartlander” meant the average HDB dweller, usually in the Outside of Central Region (OCR), with modest incomes, who is focused on bread-and-butter issues.

With the rise of the term, there was now an implied contrast between heartlanders and higher-income, more cosmopolitan types.

Heartlanders were in contrast to those who own private property and live in prime regions like the city centre or city fringe. This characterisation persists till today, and it shows how the housing we own affects our (perceived) socioeconomic standing.

More from Stacked

We Have $250k Cash After Selling Our BTO: Should We Buy A $1.5m New Launch Condo Or Resale?

Hi there! Thank you for sharing the useful articles. It has been enlightening and eye opening reading all the different…

It’s worth noting that because public housing is home to such a broad cross-section of society (over 80 per cent of the population), it’s sometimes said to blur class divisions more than in many countries.

A middle-income family in a new HDB flat and a lower-income family in an older rental block may live minutes apart and share the same public spaces, schools and markets. This supposedly helps foster a sense of common experience.

I disagree. Being able to see how much wealthier someone is, when they’re right across the street from you, fosters division in my opinion (but that’s only an opinion as valid as any other.)

3. We use housing plans as part of the multi-cultural initiative

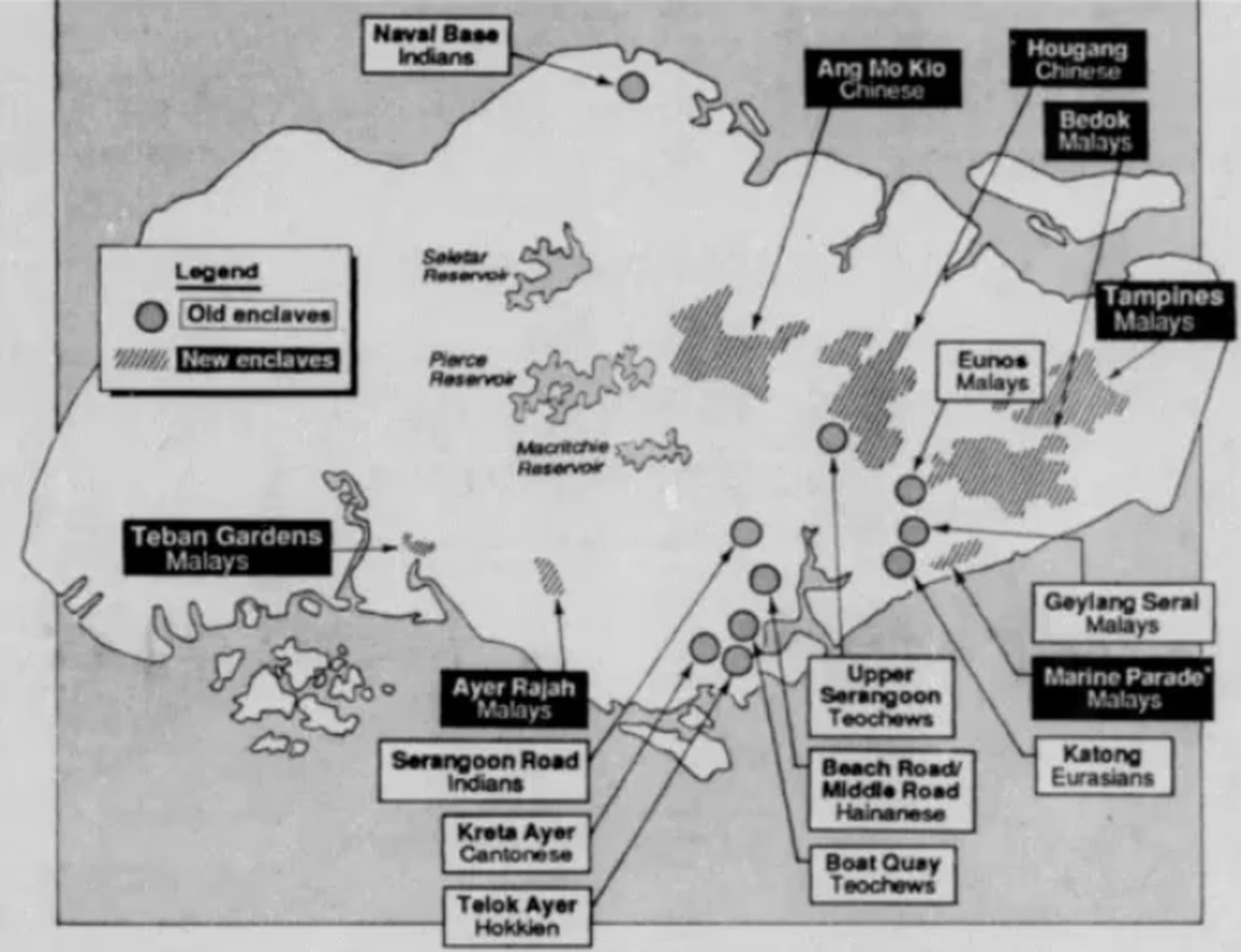

Multiculturalism is hardcoded into where and how we live. I’m talking about the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP), introduced in 1989.

In most countries, neighbourhood segregation happens naturally over time, often along income and cultural lines. In Singapore, the situation is more choreographed. The EIP sets ethnic quotas for HDB blocks and neighbourhoods based on national proportions. If a block has already reached its cap for a particular group, resale is restricted to maintain balance. This method – housing used as a tool for social cohesion – is a bit of a sticking point.

Some people see this as a form of social engineering. Others view it as necessary maintenance of a fragile peace. Either way, what it means is that most Singaporeans have grown up with neighbours of different ethnicities, seen their wedding setups, smelt their cooking, heard their festivals, and learned (usually by trial and error) how to live with one another.

(Although someone snarky might ask why heartlanders are then considered less cosmopolitan.)

Regardless, this is not an experience you get from just a National Day Parade or a social studies textbook. It’s what you get from daily exposure: using the same lift, sharing the same complaints about economy rice prices, and just seeing each other as real human beings, thus dissociating from stereotypes.

Sure, there are occasional tensions. The EIP has also been criticised for creating disadvantages in the resale market, particularly for minority sellers. But at a macro level, it means the abstract idea of multiculturalism is lived and not just preached. You can’t say that about many countries.

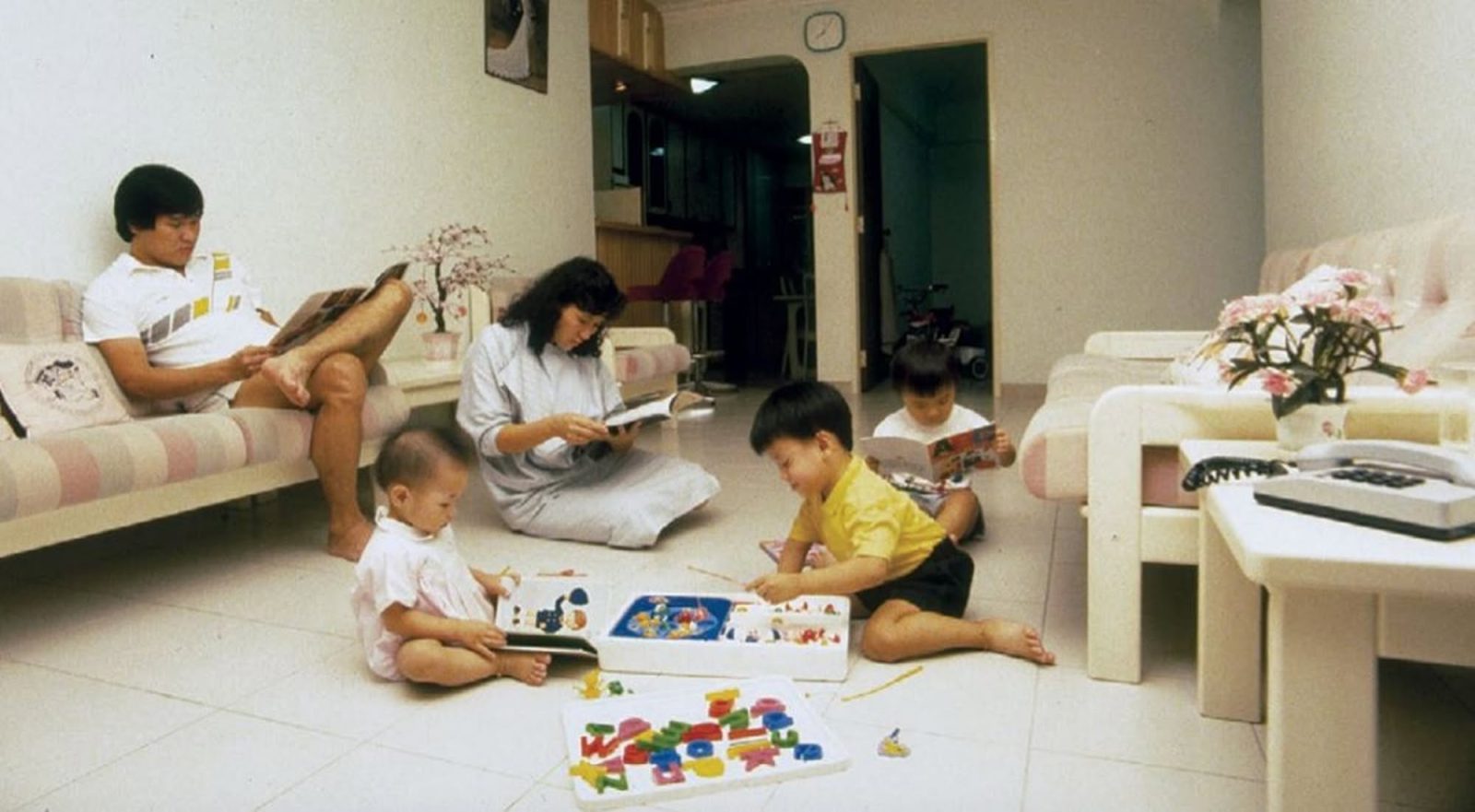

4. Securing a flat and starting a family are deeply intertwined

In most countries, starting a family means figuring out where to live. In Singapore, figuring out where to live tends to come first. The flat is not just a home; we see it as a prerequisite to adulthood.

That’s why couples queue for BTOs like they’re booking the rest of their lives in advance. We graduate, start jobs, finally get our keys, and family planning is found at the very end of that line.

And looming over all of this is the policy maze. There’s an entire lexicon – MOP, MSR, BTO, PLH, etc. – that affects family decisions. Your Home School Distance, for example, can dictate where your children study; and your MOP (which locks you there for five or 10 years) follows up to enforce that.

The high home ownership rate gives us stability; but it also creates a norm where our housing needs can end up dictating when we start a family, or how big a family.

This is going to be an ever-bigger issue going forward, as our society ages and birth rates slow.

5. Housing is both the dream and the pressure cooker that drives it

We don’t just buy homes in Singapore, we aspire to them. For most of the recent decades, home ownership has been portrayed not just as shelter, but as success. Condo or landed home ownership is what we work toward, upgrade/downgrade from, and eventually pass on. As most Stacked readers will know, a good number of Singaporeans even see their flat, condo, or landed home as a retirement plan.

This is a double-edged sword: it does make us go-getters, but it also feeds into a relentless sense of performance. You’re not just buying a flat you’re comfy in, you’re embarking on a property wealth journey.

To some, upgrading to a condo is a national rite of passage; especially if their friends have already done it. And if you’re renting past the age of 30, be ready to receive a ton of unsolicited property advice from relatives who are all suddenly well-informed property tycoons.

But love it or hate it, it is a prime example of how property ownership and housing are very much part of the Singaporean DNA. And when you see all the raging debates and obsession about property, this is exactly why: it’s not just about real estate, it’s a part of our identity.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Editor's Pick

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Advice We Can Buy Two HDBs Today — Is Waiting For An EC A Mistake?

Singapore Property News Why The Feb 2026 BTO Launch Saw Muted Demand — Except In One Town

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News The Most Expensive Resale Flat Just Sold for $1.7M in Queenstown — Is There No Limit to What Buyers Will Pay?

On The Market Here Are The Cheapest 4-Room HDB Flats Near An MRT You Can Still Buy From $450K

Singapore Property News Why Housing Took A Back Seat In Budget 2026

0 Comments