Tell someone you’re considering actually paying the Additional Buyers Stamp Duty (ABSD) on your second home, and watch as their eyes pop out. They’ll rattle off a whole bunch of reasons how you can avoid it – from buying dual-key units to decoupling.

But while those are valid methods, there are situations when it may be better to just bite the bullet, and pay the ABSD. In fact, trying to avoid the ABSD may even end up costing more. Here’s what you need to consider when working out the numbers:

- Trying to decouple when one spouse already owns another property

- Decoupling within the first three years of acquiring your existing home

- Legal implications of decoupling

- The high cash outlay when buying under trust

1. Decoupling may be more expensive than paying ABSD

Decoupling is when one borrower transfers their share of a private property to a co-borrower (typically their spouse). As the borrower would no longer own property after the transfer, they are free to buy another property under their own name, without incurring ABSD.

However, decoupling is not free; there are situations where it may actually be cheaper to pay the stamp duties. A typical example of this is when the spouse receiving the share of the property already owns another home. For example:

Say you and your spouse are currently the co-borrowers, for a $2 million property. Besides this, your spouse – for reasons of inheritance or otherwise – also owns an existing, smaller property. You’re both Singapore Citizens.

You each own 50 per cent of the $2 million property. You decouple, transferring your half of the property (a value of $1 million) to your spouse. This would incur a Buyers Stamp Duty (BSD) of $24,600.

(Note: all stamp duties are based on the higher of the price or valuation, so you cannot get around this by trying to price your property at $1).

However, your spouse already has an existing property. As a result of this, your spouse needs to pay ABSD on the share being transferred to her. This comes to an additional $120,000 (12 per cent of the $1 million being transferred).

At this point, the stamp duties paid are already $144,600.

You then have to pay legal fees for this process, which are in the range of about $5,000.

Next, you need to talk to your bank about restructuring the mortgage. Assuming you have no penalties for doing so, you can still be saddled with conveyancing and administrative fees of around $2,500.

This comes to non-recoverable expenses of about $152,500 so far.

Now, consider if the next property you intend to buy is just an $800,000 compact unit. Paying the 12 per cent ABSD on this property would only cost $96,000. It would make more sense to pay the ABSD, rather than decouple to avoid it.

As an aside, note that if your spouse is a Permanent Resident, there would be 15 per cent ABSD ($150,000) instead.

If you’re uncertain whether decoupling makes sense for you, drop us a message on Facebook. We’ll help you work out the potential costs you face, versus the ABSD on the property you’re trying to buy.

*Note that as of April 2016, decoupling is not allowed for HDB properties barring special circumstances such as divorce, change of citizenship, or the death of a co-borrower.

2. Decoupling within the first three years of acquiring your existing home

If you’re in a situation where you absolutely must get a second property within the three-year SSD period, it may be cheaper to pay the ABSD instead.

The SSD is 12 per cent of the sale in the first year, eight per cent in the second year, and four per cent in the third year. This is charged when you transfer the property to your spouse.

For example, say you want to decouple within the first year of buying a property with your spouse. The property is worth $2 million, and you both own 50 per cent.

More from Stacked

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

10 Expert Hacks for Decorating a Rental Apartment

Maybe you can’t knock down the wall between your kitchen and dining room or pull up the wall-to-wall carpet, but…

When you transfer the property to your spouse, you would need to pay the SSD of $120,000; and then your spouse still incurs the BSD of $24,600.

As with point 1, if the property you’re trying to buy is just $800,000, you should just pay the $96,000 ABSD instead.

On a related note, look out for home loan lock-in clauses. If your home loan has a prepayment penalty period (often applies in the first three to five years), you could also end up paying penalties of up to 1.5 per cent of your outstanding loan. That may also justify paying the ABSD, after it’s added to the SSD and other costs.

Property Market CommentaryWhy Are Some Homeowners Being Advised To Take Lock-in Home Loans?

by Ryan J. Ong3. Legal implications of decoupling

You need to consider the ramifications of events like divorce; that could mean you’ll get nothing from the previous property, however much of it you may have paid for it (even if you can contest it in court, there’s no predicting how much the legal fees will amount to).

Also, if the person who receives the full property decides to sell it, there isn’t much you can do to stop the process – this can be problematic if, say, you have an elderly parent who needs the property to live in.

Sometimes, these considerations have to take precedence over saving on the ABSD. Do speak to a conveyancing lawyer first, so you understand the risks.

4. The high cash outlay when buying under trust

You can avoid paying ABSD if you buy a property under trust for your children. However, it’s hard to turn this into a financial benefit for yourself.

Financing isn’t available for properties bought under trust. This means you need to pay for the entire property all at once. In addition, because the property is held by the trustee for your children, you cannot receive any benefits such as rental income.

Also, do remember that the property – along with any rental income – will go to your children and not you. If the intent is to benefit yourself (such as for retirement), you will have to act on total faith that your children will give you the property and money back when they receive it.

As such, a trust is useful if your genuine intent is to provide a home for your children. There are few ways for you to directly benefit from this, as you would be locking up a large amount of capital, and also paying for the establishment of the trust.

(Typically $5,000 to $12,000 based on the property value; this excludes costs such as fees for the maintenance of the property, which are typically pegged to the real or estimated annual rental income of the property).

If the property is mainly to benefit yourself, do consider if it’s better to just bite the bullet and pay the ABSD instead.

This isn’t to say that decoupling, trusts, or “sell one, buy two” are bad strategies

It’s simply that they’re not universal. A small subset of home buyers are in situations where those common strategies may not suit their intent. Do reach out to us for help if you need clarifications; and you can also follow Stacked for the latest news and trends in Singapore’s private property market.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

When is it better to pay ABSD instead of trying to avoid it?

Can decoupling help me avoid ABSD on my second property?

What should I consider if I want to decouple within the first three years of buying a property?

Are there legal risks involved in decoupling or transferring property shares?

What are the drawbacks of buying property under a trust to avoid ABSD?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

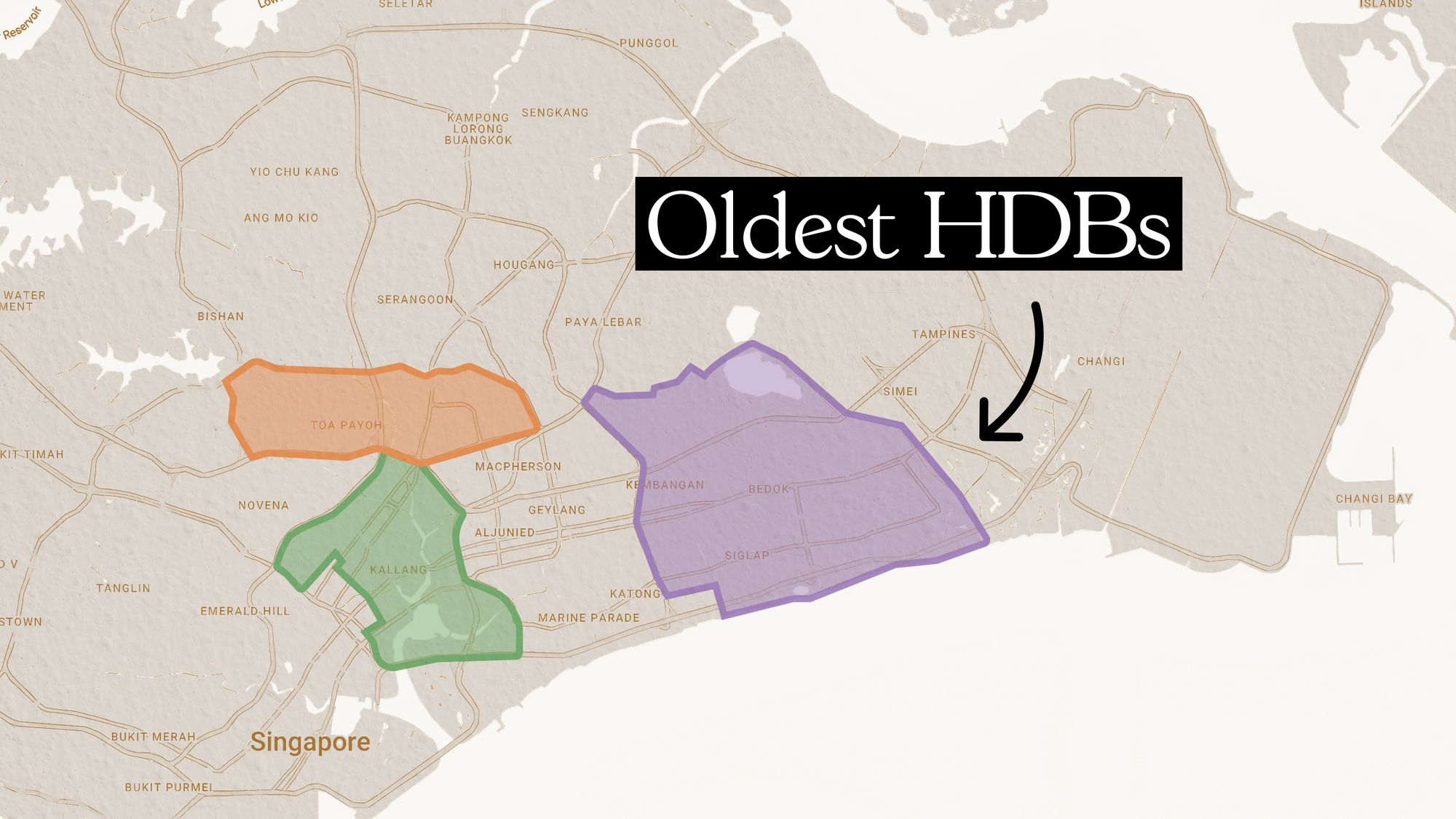

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Pro Why Some Central Area HDB Flats Struggle To Maintain Their Premium

Singapore Property News Singapore Could Soon Have A Multi-Storey Driving Centre — Here’s Where It May Be Built

Singapore Property News Will the Freehold Serenity Park’s $505M Collective Sale Succeed in Enticing Developers?

0 Comments