Are Property Prices REALLY To Blame For Our Falling Birth Rates In Singapore?

March 1, 2023

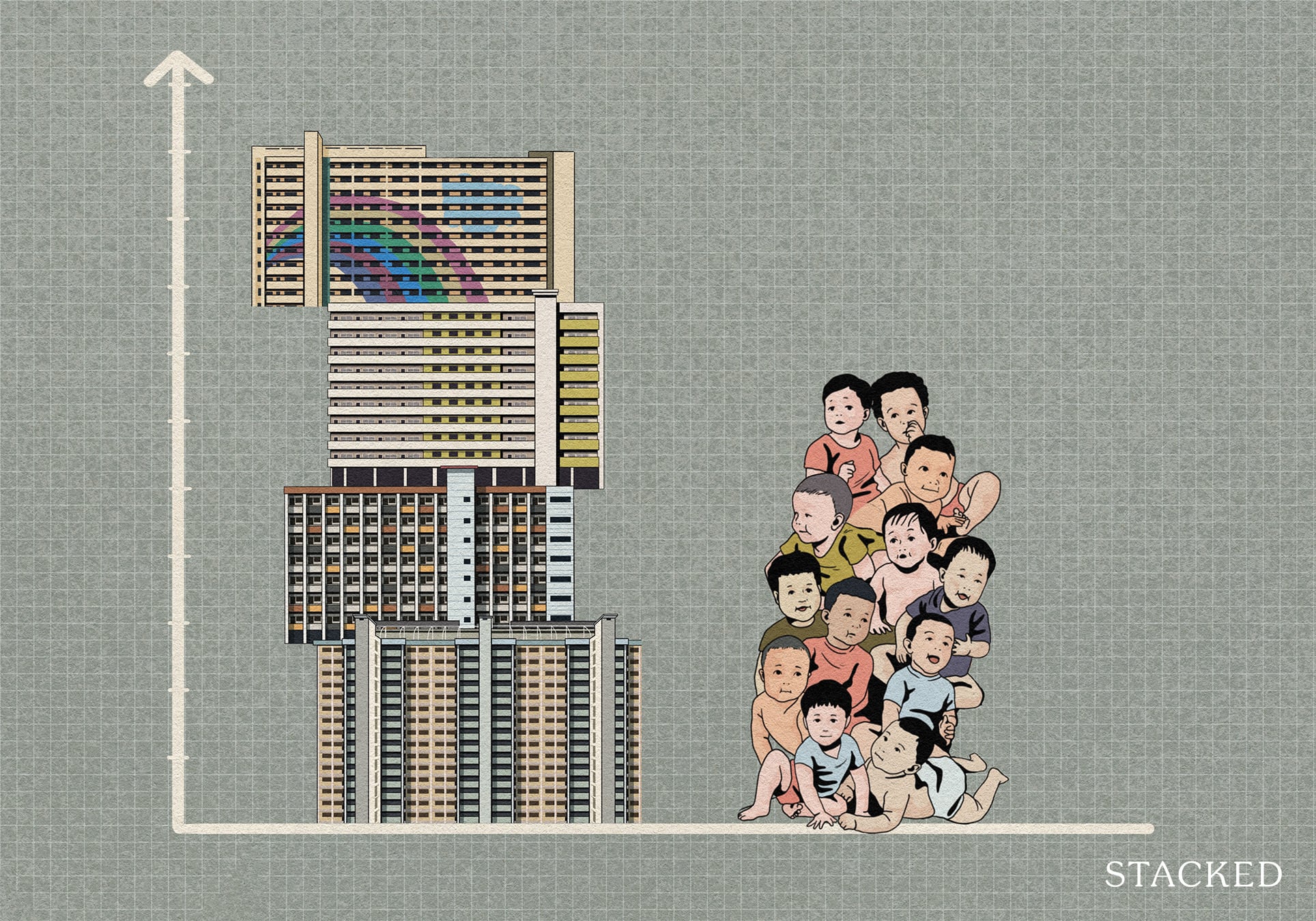

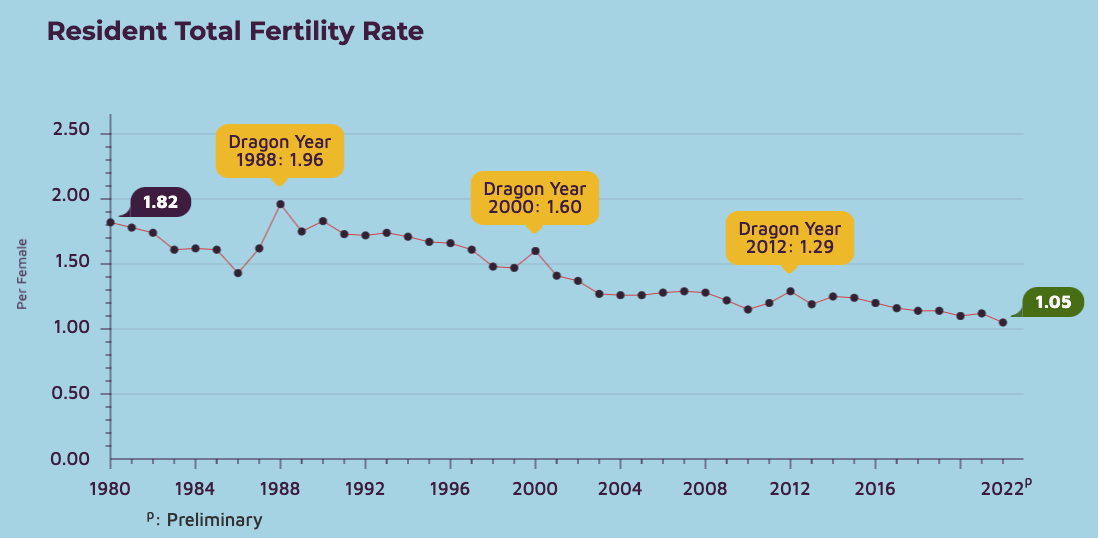

Singapore’s fertility rate was at a record low in 2022, and we’ve seen online discussions and news outlets pin it on housing prices, albeit to varying degrees. Some claim high property prices as the main cause of the falling birth rates, others call it one of many contributing factors. Either way, the two issues seem inextricably linked in the minds of Singaporeans – and we’re interested in your view/experience of the issue. To put it in perspective:

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

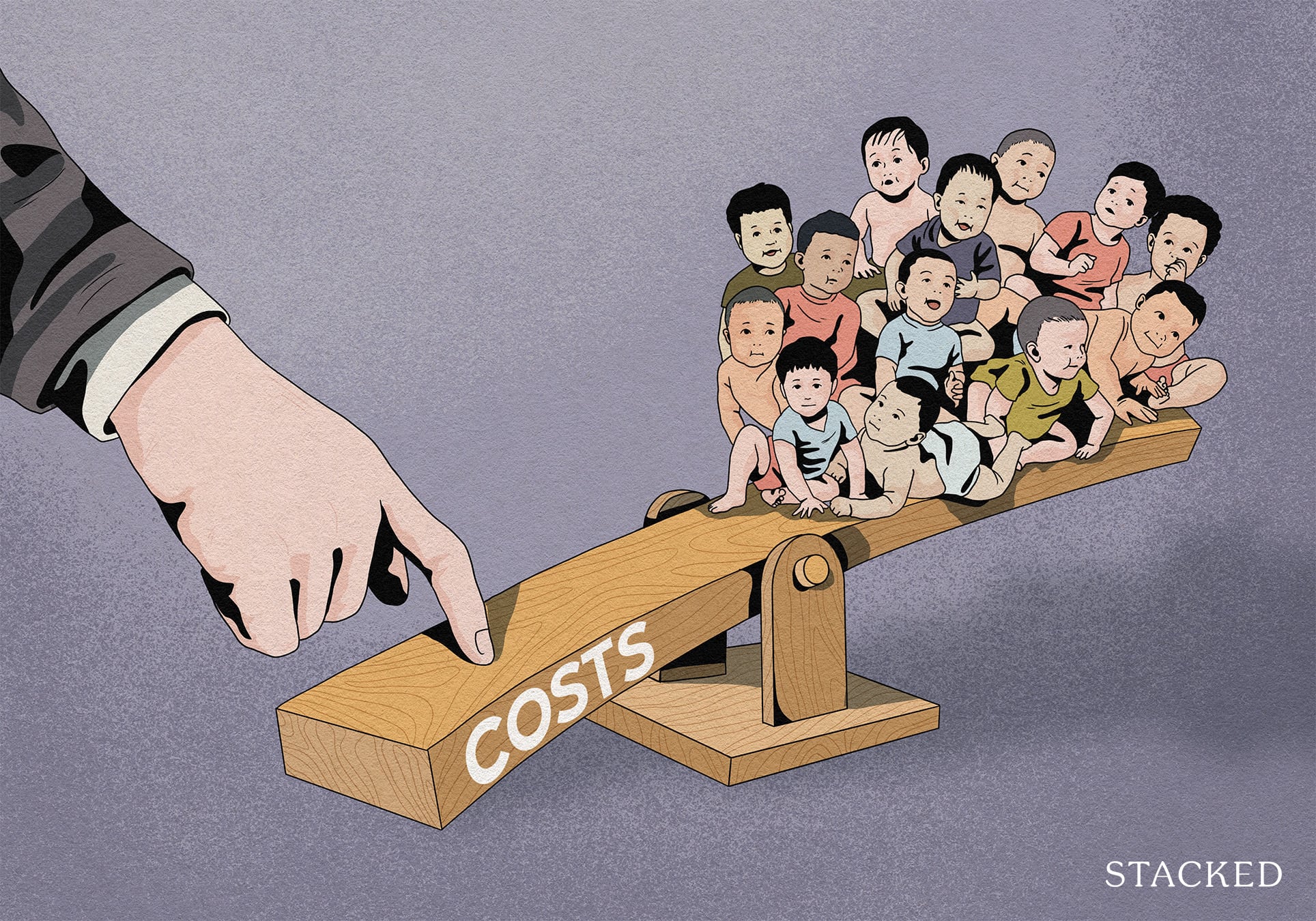

Arguments on why higher home prices = lower fertility rate

When the issue of low fertility rates came up on Reddit last year, a number of commentors were quick to zero in on housing as a factor. As one Redditor noted:

“Getting a house – good luck getting a BTO near your/her parents with the national lottery. why not resale you say? because shit is expensive and guess what, kids are expensive too.”

Another commentor said that:

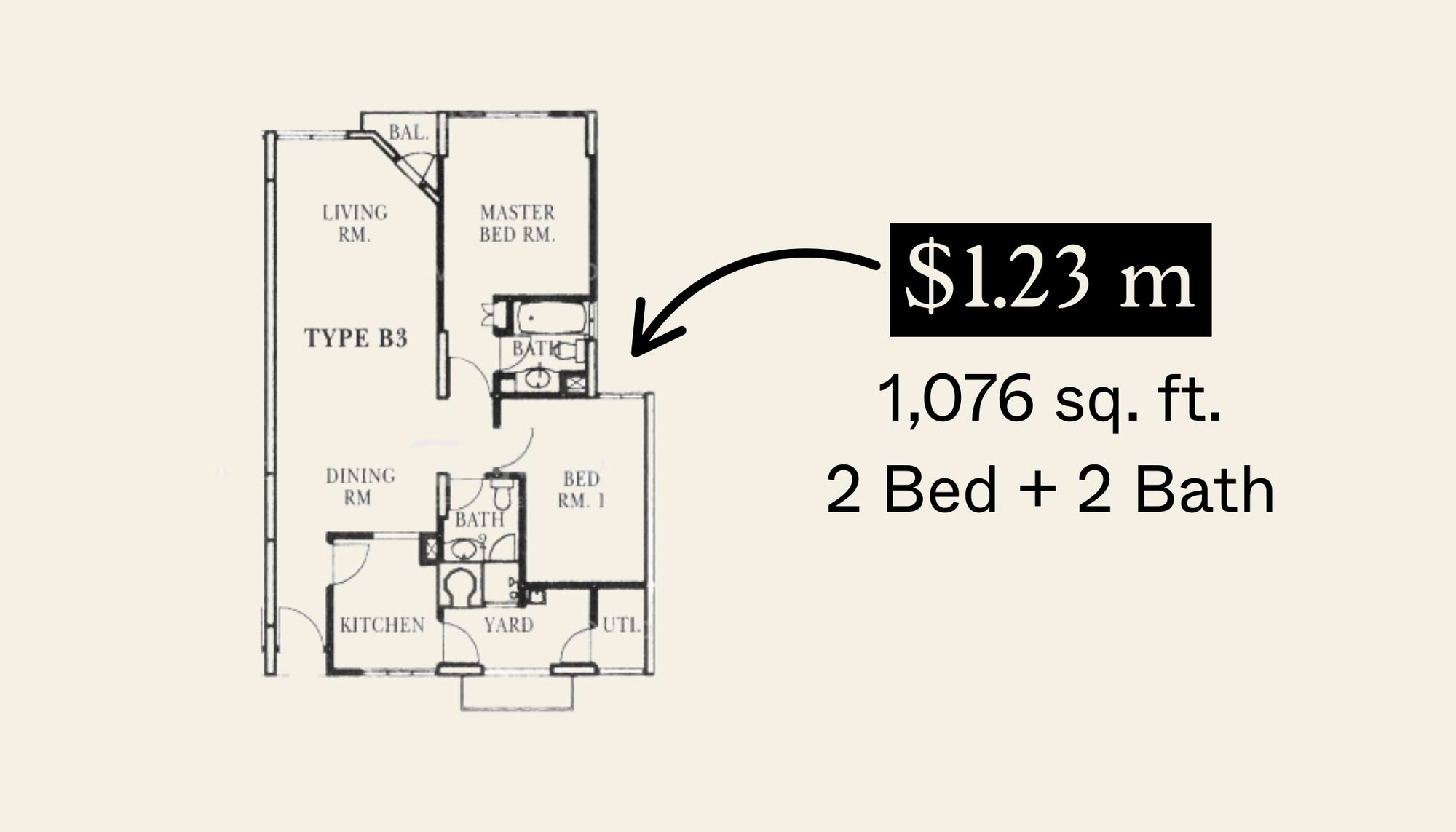

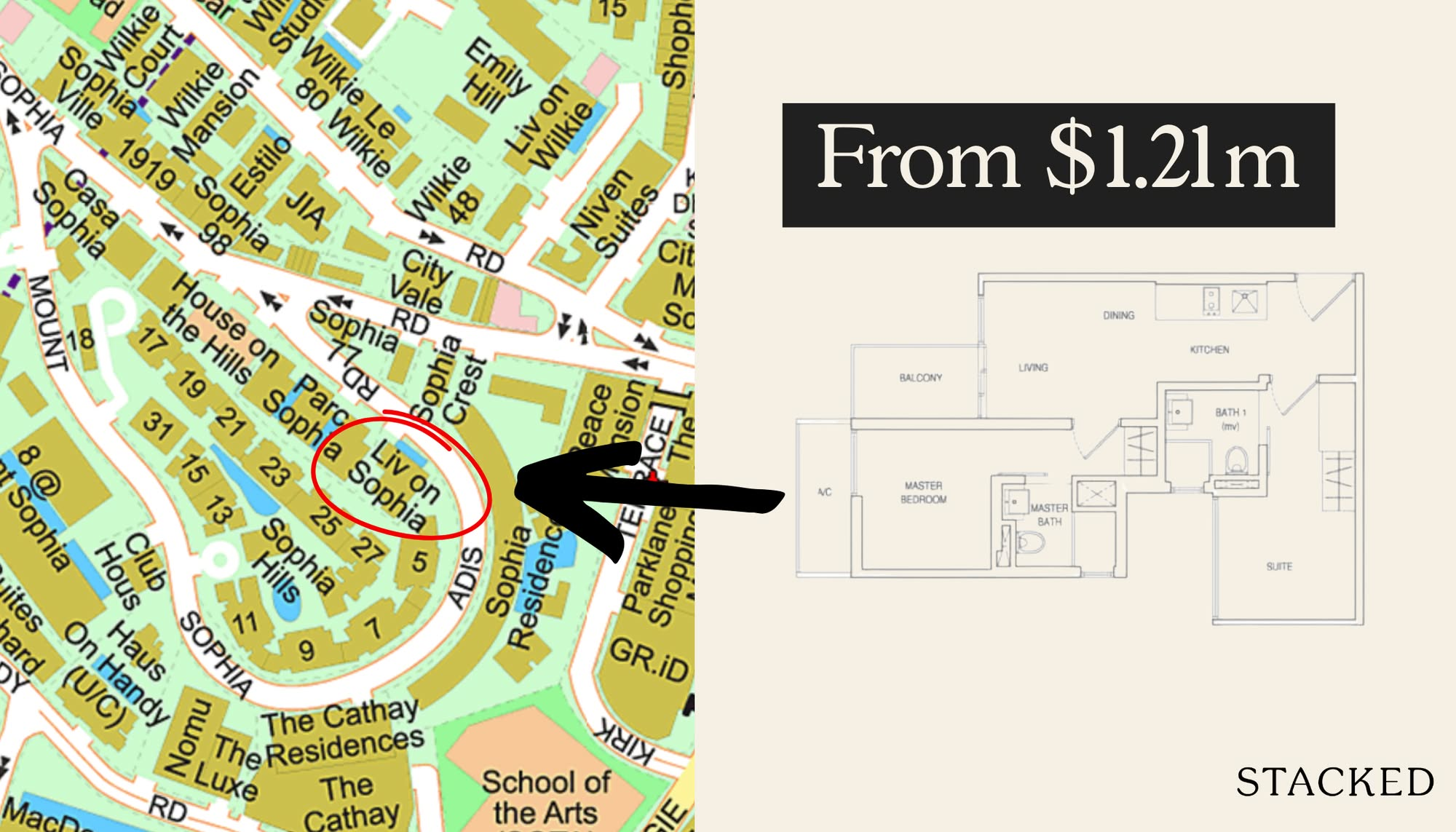

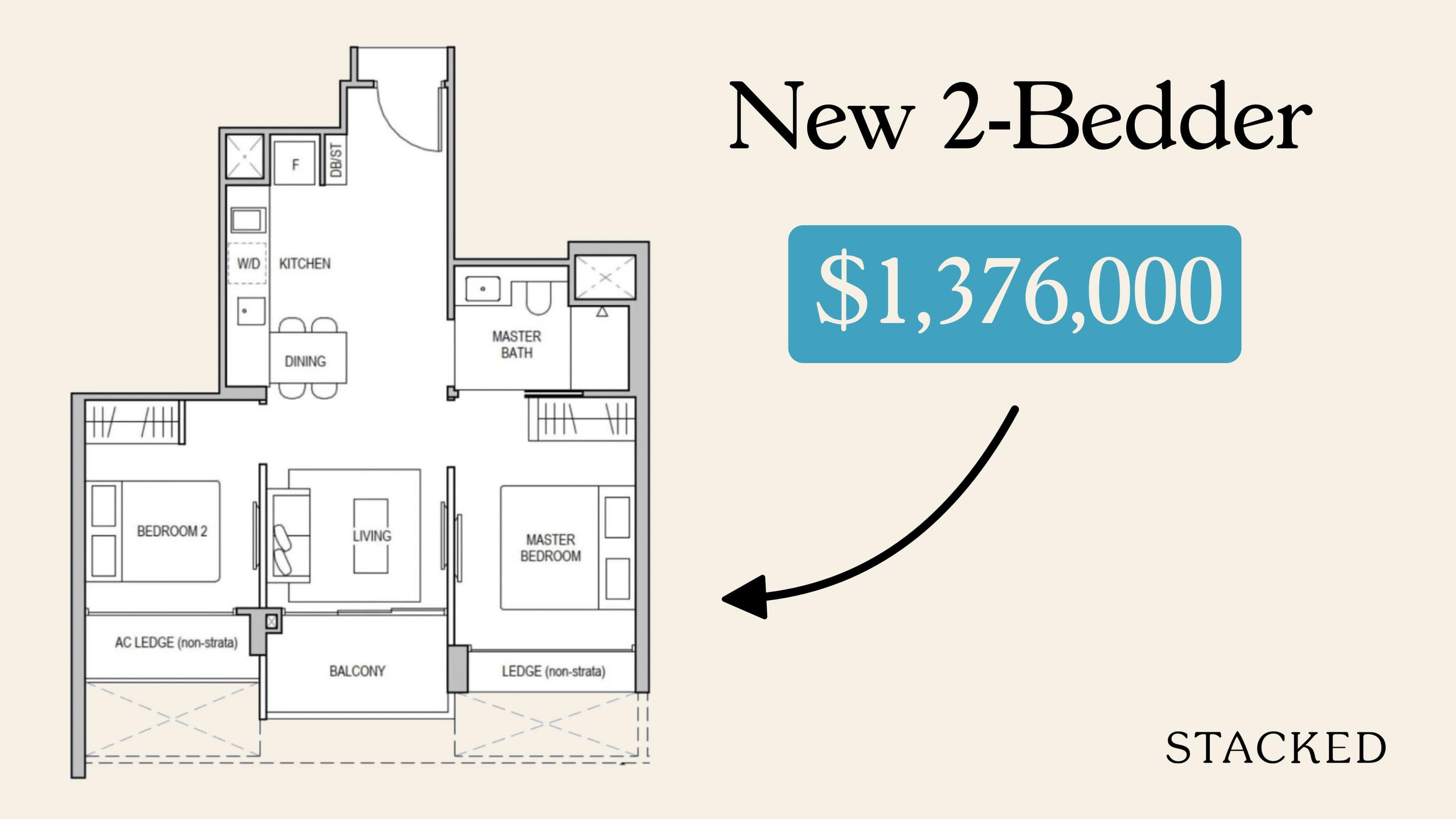

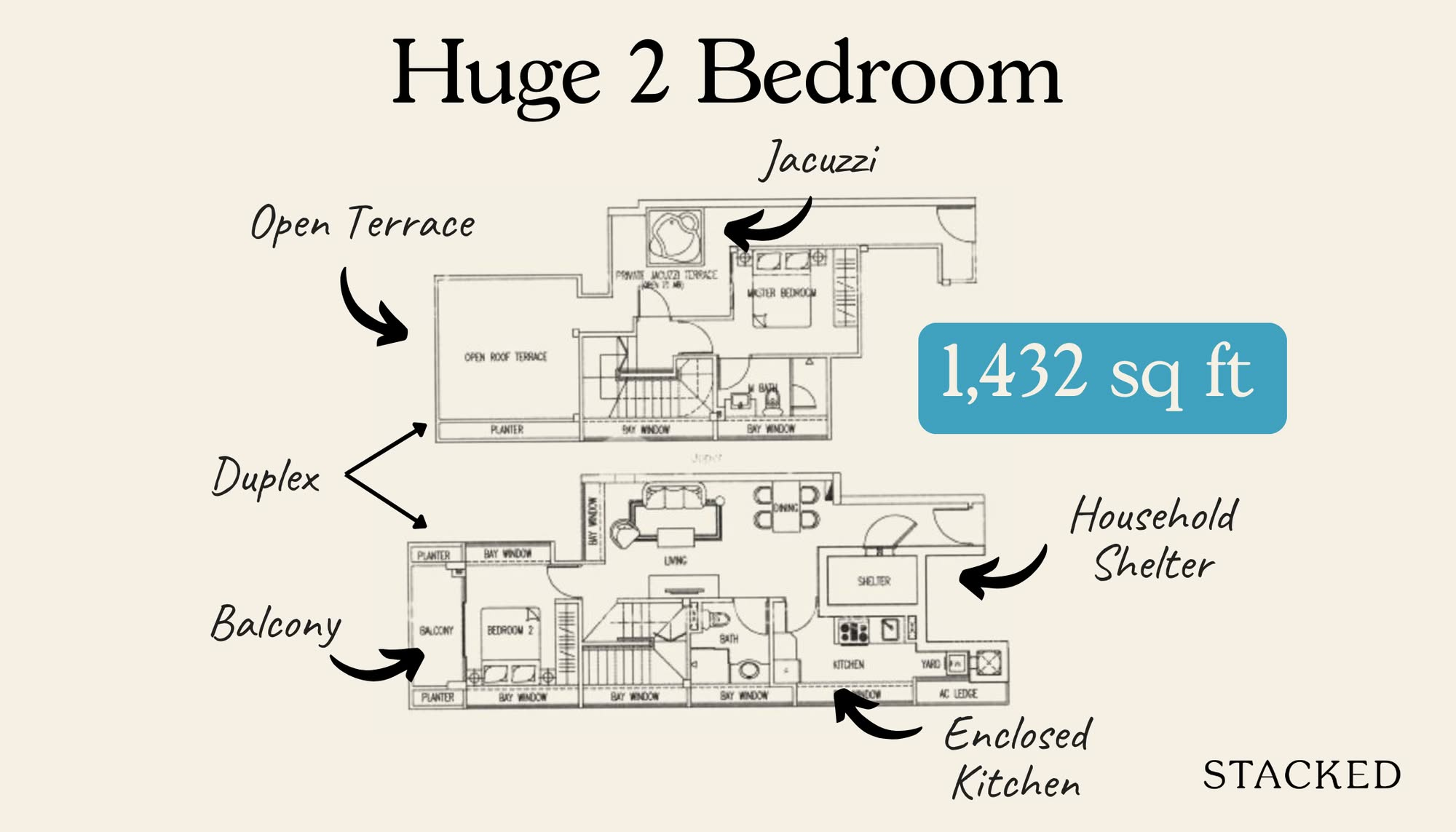

“No space. Apartments are TINY and this is an issue I cannot overlook… Housing prices, I can never understand how so many ppl can afford more than $1 million.”

Now that it’s up on the news again, the blame hasn’t shifted. More recent posts on the topic highlight the situation with flat prices:

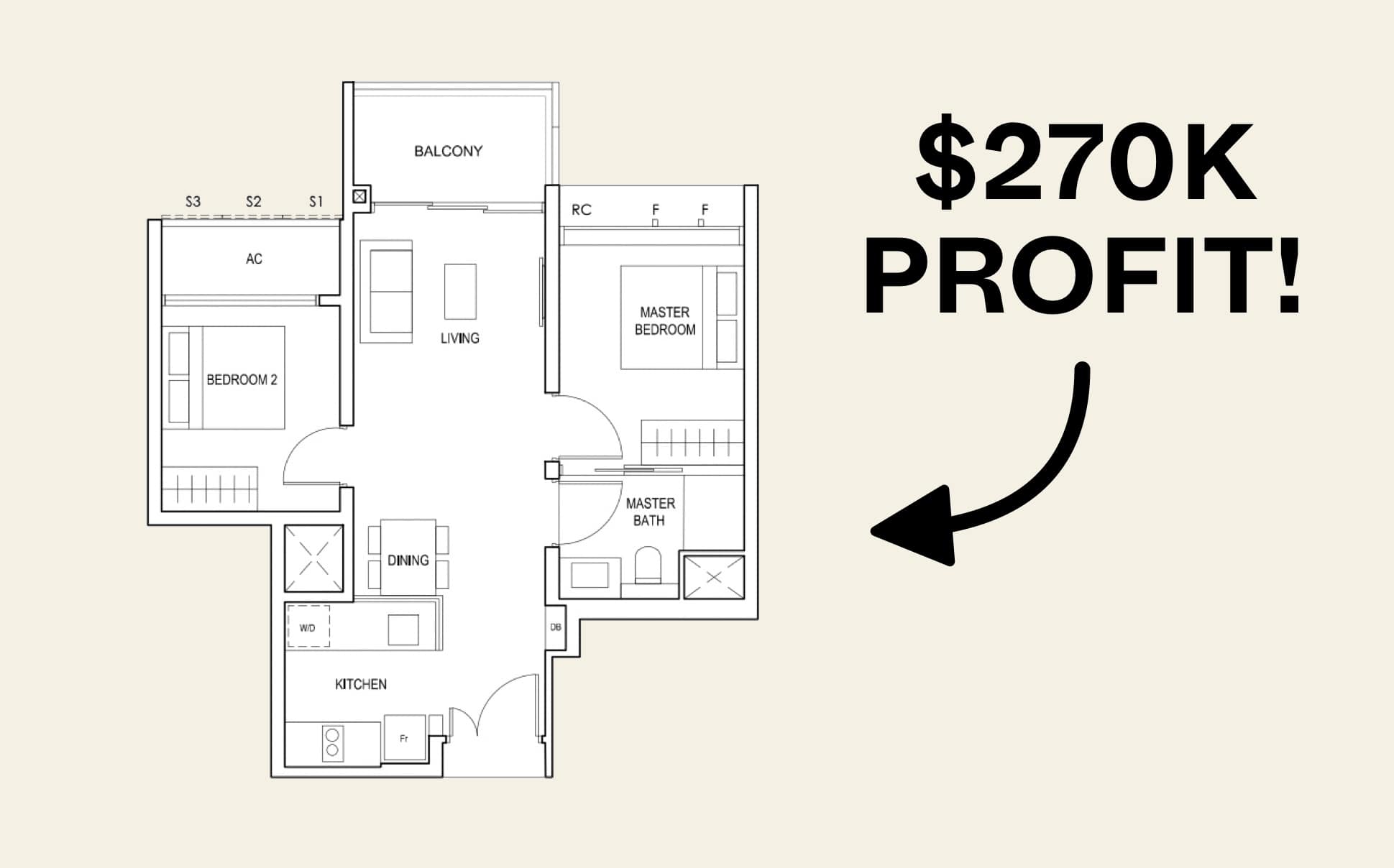

“Resale HDBs and condos are at an all-time high, BTOs are delayed (and getting pricier),” and “Well, been applying for a BTO for 2 years and got nothing. I wanted two kids – but seems like the chances of having them are slim now with no housing.”

The normalisation of a dual-income family is also a factor

With dual-income families, it’s not uncommon for grandparents or domestic helpers to become essential to the raising of children. But this is not an arrangement that sits well with every potential parent. E.g., hiring a domestic helper raises costs, while not everyone’s grandparents are available or able to look after children.

On the ground, some homeowners we’ve spoken to have also said they feel unwilling to raise “latchkey kids”, who are abandoned to their own devices as both parents are working; and some have noted that, if raising one child with two working parents is tough, two or three children will be overwhelming.

This raises the question of whether a single-income family can manage the cost of housing, while also raising a child.

How viable is this? Let’s use the 3-3-5 formula that’s meant to ensure (very) prudent home purchases.

3-3-5 suggests the buyer must have 30 per cent of the required capital before buying, the monthly loan repayment can’t exceed 30 per cent of monthly income, and the total cost of the home cannot exceed five times annual income.

The median income of a Singaporean is said to be $5,070 as of 2022.

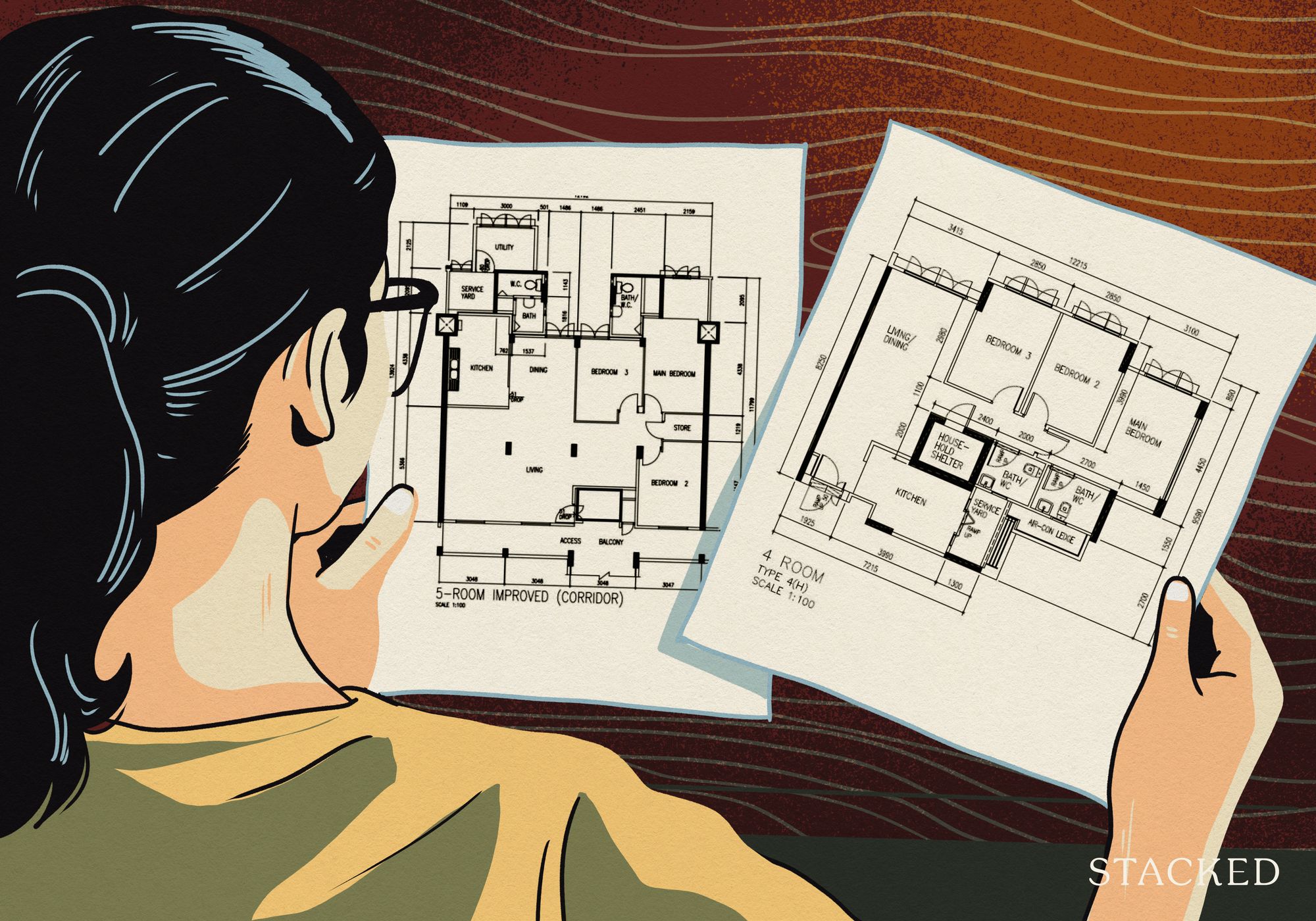

This would mean the total cost of a home, for a single median-income earner, would be around $304,200. This is roughly the cost of a 4-room BTO flat in a non-mature area, after subsidies.

This is somewhat doable, if the family is willing to settle for a BTO flat and its five-year construction time. They also have to settle for one of the cheaper non-mature areas.

If they want a 4-room resale flat, however, this becomes much tougher. A 4-room resale flat, as of February 2022, averages $555 psf island-wide (with the average 4-room being roughly 1,000 sq. ft., which comes to $555,000).

As such, single-income families seeking resale options may end up with 3-room options, which some may consider too small.

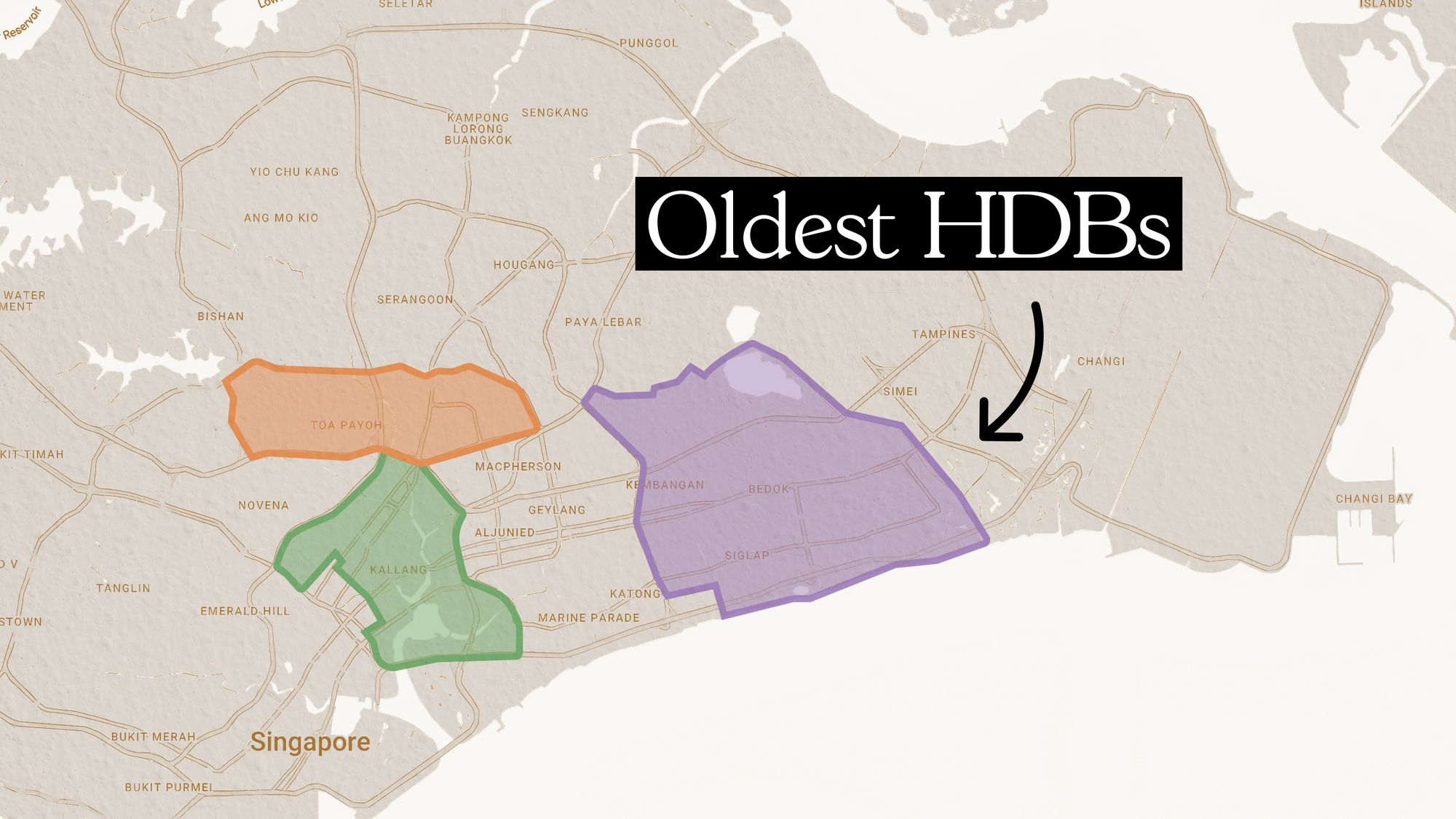

For hotspots like Bishan, Tanjong Pagar, etc., it’s possible that even BTO prices (probably under the PLH scheme) may be too expensive; and resale is almost certainly out of the question in these areas.

Next, the monthly loan repayment cannot exceed roughly $1,520 per month. Assuming our fringe-area BTO flat costs around $304,200 as above, this is a maximum HDB loan of $243,360, say over a 25-year period.

That would come to around $1,104 per month. Manageable, but again, going for resale or something bigger seems likely to push this past the 30 per cent ceiling.

We also need to consider if it’s still viable to raise children, should 30 per cent of the monthly income alone be consumed by housing. This is subjective, and not everyone will be comfortable with it.

Finally, a buyer needs sufficient capital (around $65K in this case) for stamp duties, legal fees, initial down payments, etc. This seems possible even on a single income, thanks to accumulated CPF savings; but we daresay $65k is an amount that most individual buyers would still need to plan for.

From word on the ground, many readers do feel that a single income is cutting it too close in Singapore.

It’s also a lifestyle issue: after paying for the house and child, one could end up with a lifestyle without room for vacations, others passions to pursue, aspirations like starting a side business, etc.

As one reader remarked after such a conversation:

“So I have to choose between not having enough time for the child if I work, or making the child live a deprived life if I don’t work. Then why raise a child just to share the misery?”

More from Stacked

Why This Rare New Queenstown Condo Nearly Sold Out Even At $2,800 Psf

When you mention Margaret Drive, most people will think of million-dollar HDBs. But while Dawson has become a household name…

To date, we’ve been unable to find studies that show how the number of dual-income families has (or has not) increased over the past decades. It’s a pity, as otherwise, we could compare the fertility rate to the rise in dual-income households.

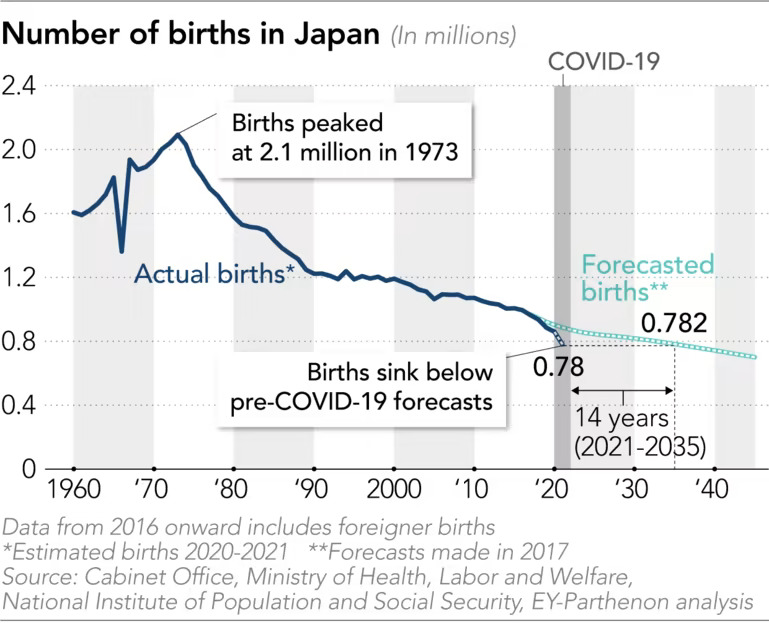

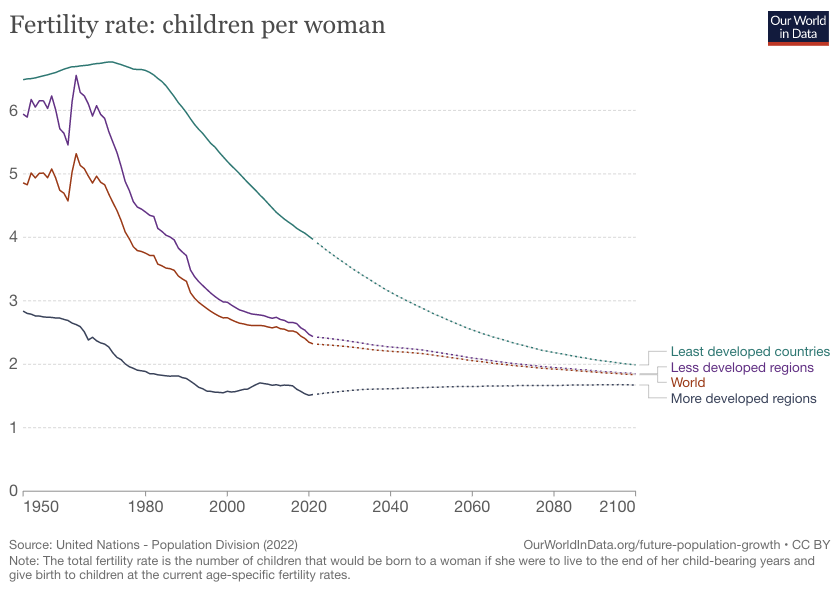

But at the same time, every developed country has similar population problems

A close comparison is Japan, and we can’t help noticing the discussions follow the same general tangent. While there’s less specific blame for its property market, comments centre around work culture, the economy, and the choice of higher income over family time.

Ultimately, that still parallels the discussion in Singapore, where the issue is the affordability of having children (our only real difference is that we identify housing as the main financial issue).

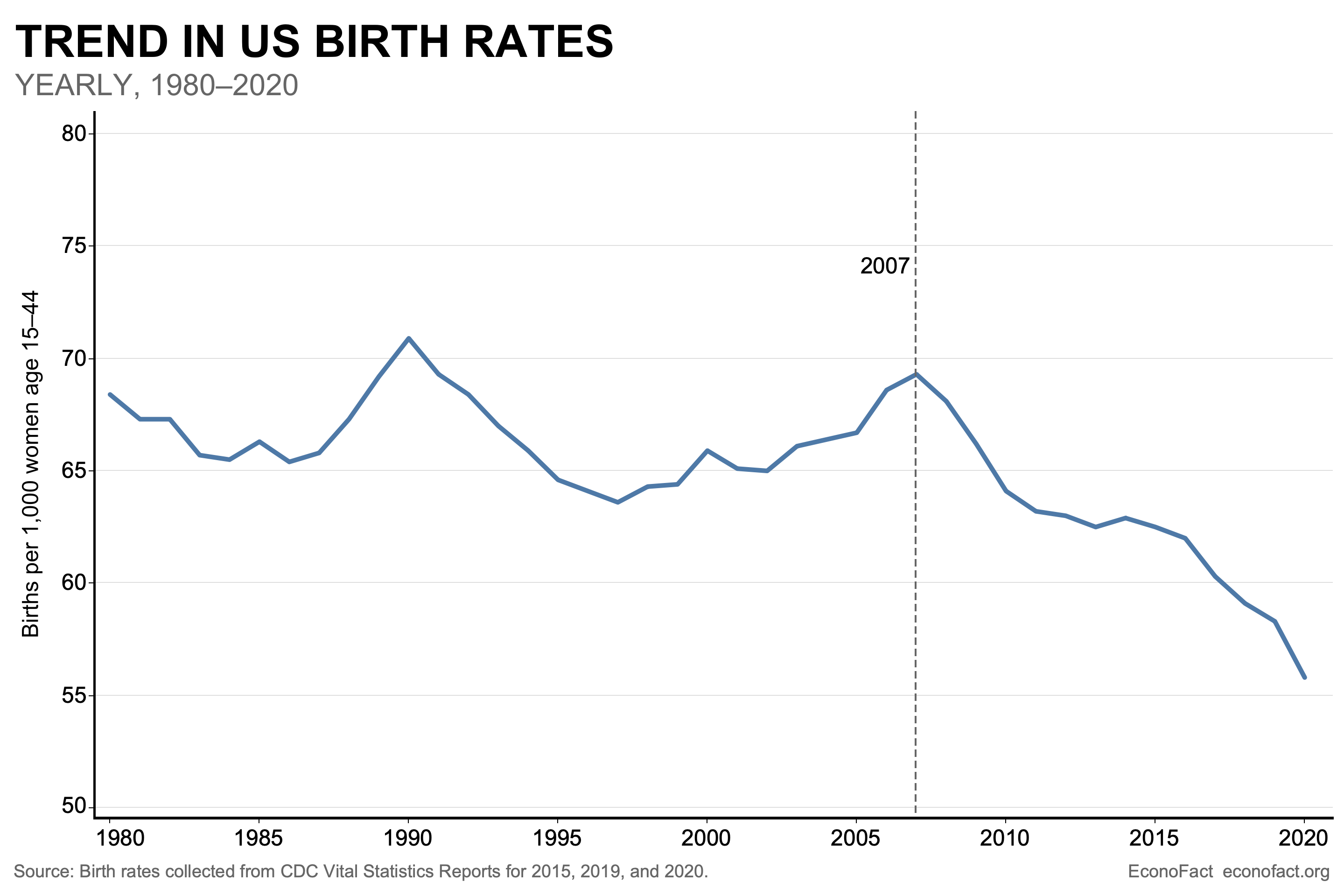

In the United States, the bellwether for the developed world, more people are also choosing to have fewer children; if not remain outright childless. Here too, some fingers are pointed at housing; and studies show that rising rent (homeownership rates are lower in the US, and home ownership is not as normalised as it is in Singapore) results in falling birth rates.

But this also reveals a tendency for developed countries to have lower birth rates; and it may not be specific to housing. One Redditor, commenting on the situation in Japan, feels that financial factors and housing are red herrings:

“I’ve talked about this issue for years on Reddit by now and was never taken seriously until very recently when people started realizing this is a global phenomenon with no real solution to it.

Sadly most of the world isn’t learning from us in Japan. The west is now making the exact same mistakes by first thinking it’s financial in nature, then thinking it has to do with unhappiness or depression. Next will be thinking it has to do with a housing crisis. Only to eventually realize it has to do with people having too high quality of life and children simply being a detriment in quality of life over your ~90 years of existence you have in this world.”

In short, developed countries have lower fertility rates because we choose to do other things in our lives than raise children. We’re not in a position where we’re forced to do it out of circumstance, and we have different aspirations from those in less ideal circumstances.

This is also visible regarding women’s empowerment: in developed countries, women have opportunities that go beyond the household. In a local context, for example, we’d need to ask if a woman who has, say, a Masters’s degree and a CEO position would want to surrender all that, to raise children.

(Or if you flip the gender roles, how many men would surrender that to be, say, househusbands?)

This point of view suggests that, even if it were possible to make housing, education, the cost of raising children, etc. cheaper, it still wouldn’t move the needle on our fertility rate.

The phenomenon of development/industrialisation leading to lower fertility was recognised even in the 1960s when economist Gary Becker linked it to economic models. The argument put forward was that high-income families place less value on child-rearing than the poor.

To over-simplify a little, a high-income family in a developed world doesn’t need a large number of children, unlike a poorer one with a high mortality rate. It’s also a different environment from, say, a rural backwater where more children literally translate to more hands to keep the farm (or whatever family business you have) going.

Even when we do have children, we’re likely to invest more in one or two children (e.g., overseas education, tertiary education, enrichment classes), than to spread out the resources evenly over four or five children.

That last bit likely resonates with Singaporeans, who probably won’t prefer four or five children with only Secondary school education, versus, say, just funding one child who ends up with a degree or a master’s.

Again, this is an oversimplification of a complex and nuanced argument (do check out Becker’s work if you can), but the tl;dr version is that developed countries prefer quality to quantity.

If we were to go by that argument, our fertility rates may remain low even if we were to ramp up housing.

Which is the bigger impact on our fertility rate: housing and economics, or new lifestyle preferences?

Or do you perhaps think it’s a mix of both? And if you were given a shot, how would you try to rectify the situation? Do let us know in the comments below.

We’ll keep you updated on the news and debates in the Singapore property market as they unfold, so do follow us on Stacked. In the meantime, you can also check out reviews of new and resale projects alike, to find the ideal home.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

Is high property price the main reason for Singapore's low birth rates?

How does housing affordability affect families wanting to have children in Singapore?

Can a single-income family in Singapore afford to raise children and buy a home?

Are lifestyle choices in developed countries like Singapore contributing to lower fertility rates?

Does improving housing affordability alone solve Singapore's low birth rate issue?

What other factors besides housing are influencing Singapore's low birth rates?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary A 60-Storey HDB Is Coming To Pearl’s Hill — The First Public Housing Here In 40 Years

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News New Tampines EC Rivelle Starts From $1.588M — More Than 8,000 Visit Preview

Singapore Property News Executive Condo Prices Have Doubled In A Decade — Raising New Questions About Affordability In 2026

Singapore Property News River Modern Sells Over 90% Of Units At Launch — Here’s What Buyers Paid

1 Comments

More nuance needed for fertility problem. Reasons for choosing to have 0 vs 1 child, are quite different from choosing to have 2 vs 3 children. The broad 1.05 has lumped it altogether as a singular issue to tackle. Also I have a question actually, does everyone really want housing to be cheaper year after year? Existing and in fact potential house owners wouldn’t want that right?