The Surprising Lifespan Of Freehold And Leasehold Condos In Singapore: What Age Do Most Condos Go En-Bloc?

August 27, 2023

Singaporeans love freehold properties; and in many discussions, there’s an emphasis on the permanence of a housing asset. Many feel that a leasehold property is too transient, or complain that even a freehold property might be seized by the government. But behind all this, there’s an important question that’s rarely asked: How long does the typical condo survive in Singapore? Or to put it simply, how much of the 99-year lease actually gets used? We took a deeper look:

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

When do most condos that go en bloc sell?

To date, we have yet to see a single residential project reach the end of its 99-year lease. In fact, the only time we’ve seen a residential project reach the end of its lease was in Geylang Lorong 3, when 191 units reached the end of their 60-year lease.

So when it comes to the condos in Singapore, especially those that are 99-year leasehold in nature, just how many would end up going en bloc?

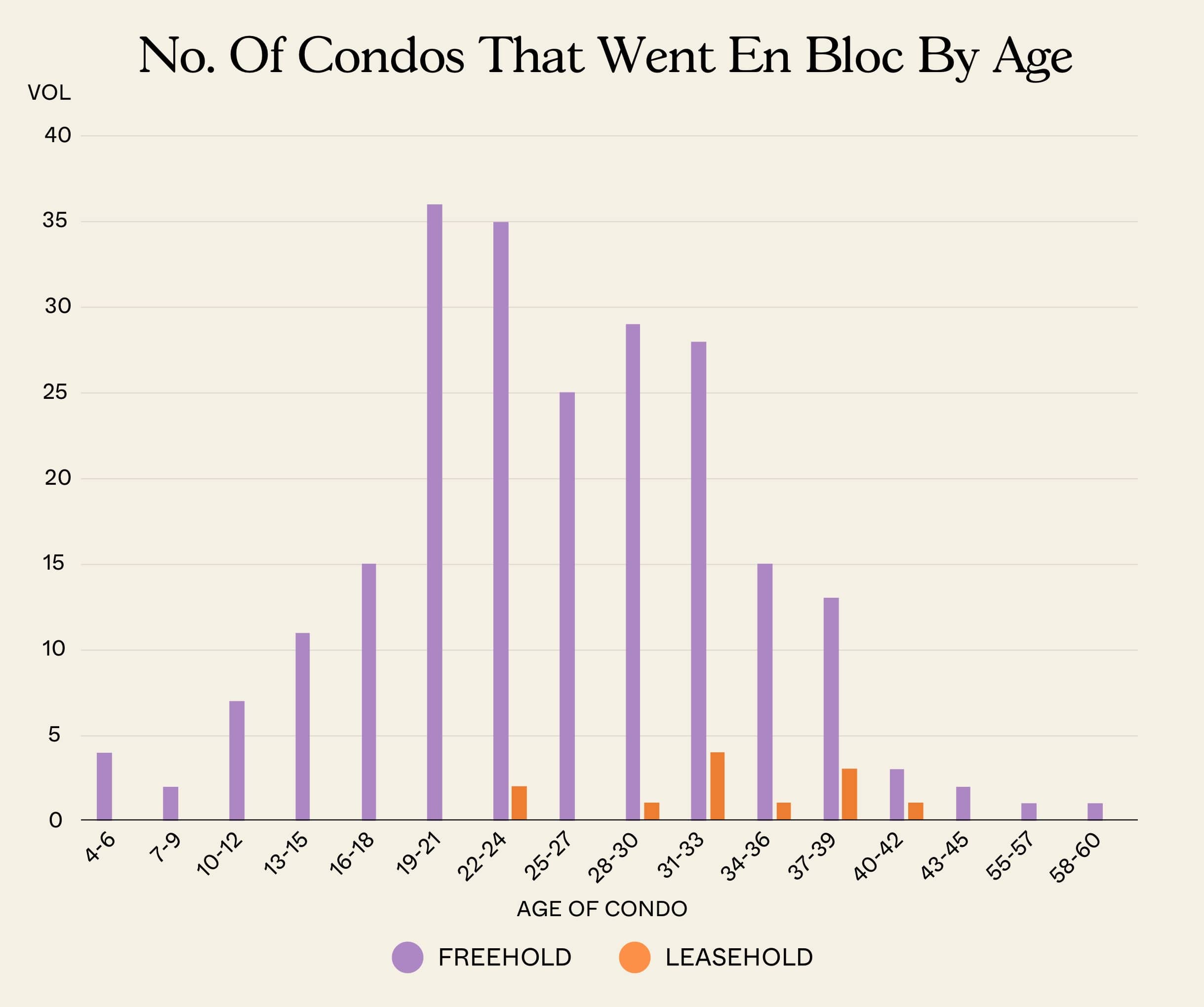

First, let’s have a look at condos that already went en-bloc to see at what age they’re likely to be sold.

If we combine both leasehold and freehold properties, we can see that most residential projects were redeveloped after 19 to 24 years.

There are also many condos that went en bloc between the ages of 25 to 39. Thereafter, the number of projects going en bloc after 40+ years is in the single digits and is rare enough that most market watchers can name them (e.g., People’s Park Complex, Pandan Valley). This is likely because there aren’t that many condos of this age to begin with. Those that survive this long probably underwent attempts to go en bloc before, or tried to gain interest from developers only to be met with setbacks that are still present today.

As an interesting aside, the shortest-lived condo project in Singapore was a freehold project. This was iLiv @ Grange, which went en-bloc after three years (this was redeveloped as Grange 1866). This is a good indicator of how willing we are to tear down and rebuild, if not for government measures like ABSD deadlines.

Also, while it may seem like freehold condos form a large majority of en-bloc deals, this may just be because of the number of small freehold condos around. Many older developments are also freehold – but the tides could shift as the government no longer sells freehold land to developers.

If we look in terms of the number of units rather than the number of condos, a different picture can be seen – especially over the last few years:

| Year of en bloc | Freehold | Leasehold | Insufficient Data | Freehold Proportion | Leasehold Proportion |

| 1995 | 39 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 1996 | 164 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 1997 | 94 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 1999 | 92 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2000 | 124 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2002 | 101 | 56 | Unknown | Unknown | |

| 2003 | 273 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2004 | 311 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2005 | 1467 | 49 | 97% | 3% | |

| 2006 | 3568 | 895 | 80% | 20% | |

| 2007 | 4219 | 2208 | 66% | 34% | |

| 2008 | 63 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2009 | 141 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2010 | 680 | 21 | 97% | 3% | |

| 2011 | 1307 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2012 | 512 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2013 | 233 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2015 | 45 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2016 | 53 | 533 | 9% | 91% | |

| 2017 | 851 | 1886 | 31% | 69% | |

| 2018 | 1891 | 1255 | 60% | 40% | |

| 2019 | 113 | 229 | 33% | 67% | |

| 2020 | 75 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2021 | 255 | 100% | 0% | ||

| 2022 | 149 | 726 | 17% | 83% | |

| 2023 | 107 | 100% | 0% |

When we go by the number of units instead, you can see that the proportion changed significantly from 2016. In terms of units, the period of 2016 – 2019 saw 3 out of 4 years with leasehold developments gaining a larger share of the en bloc market (in terms of units).

While there are still more freehold units that go en-bloc overall, this can be explained by the large leasehold properties that have gone en-bloc in the past few years (the ex Rio Casa, Eunosville, Tampines Court, come to mind).

How do we know if most condos would end up going en-bloc or not?

To answer this, we should take a look at the number and proportion of condos in Singapore by age that still exist today. Then, we can look at the en-bloc numbers to see if most old condos actually went en-bloc or not.

Disclaimer: This table is derived by counting the number of condos that we have data on (2,600+ condos) and removing those that went en bloc. Reasonable effort has been put in to ensure the completion year has been recorded correctly. Main sources include URA’s transaction database and other online directories. However, there are many old developments with no completion year information, as such, we can only use this table to get an idea of just how many condos there are left at a given age to compare it against the number of condos that went en bloc in total. Do also note that the number of condos below is likely lower as some developments that went en-bloc could not be removed from the table.

| Age Range | Est. No. of Condos (With Data) | Est Proportion Of Condos |

| 4 – 6 | 110 | 4.8% |

| 7 – 9 | 303 | 13.1% |

| 10 – 12 | 265 | 11.4% |

| 13 – 15 | 261 | 11.3% |

| 16 – 18 | 197 | 8.5% |

| 19 – 21 | 212 | 9.2% |

| 22 – 24 | 186 | 8.0% |

| 25 – 27 | 189 | 8.2% |

| 28 – 30 | 147 | 6.3% |

| 31 – 33 | 90 | 3.9% |

| 34 – 36 | 39 | 1.7% |

| 37 – 39 | 131 | 5.7% |

| 40 – 42 | 81 | 3.5% |

| 43 – 45 | 31 | 1.3% |

| 46 – 48 | 42 | 1.8% |

| 49 – 51 | 10 | 0.4% |

| 52 – 54 | 13 | 0.6% |

| 55 – 57 | 5 | 0.2% |

| 58 – 60 | 2 | 0.1% |

| 61 – 64 | 1 | 0.0% |

Currently, there are close to 400 condos that are between the ages of 19 to 24. As previously mentioned, many en bloc deals occur at this age – around 70+ so far based on available data.

The 70+ that went en bloc at this age pales in comparison to the number of condos in that age range today. Does this mean that most of these condos would go on without ever achieving an en bloc?

If we look at when these condos went en bloc and work backwards the 19-24 years of age, you’ll see that many of these condos were built in an era where homes were still big and condo grounds were spacious (~80s).

Moving forward, as long as Singapore land prices continue to grow and land is scarce, we can expect en bloc sales to happen. The only question is whether or not is whether homeowners are willing to let go of it at a price that could still be profitable for developers.

This is significant to freehold investors

Freehold properties start off at a premium – as a ballpark, they would typically cost 20 to 25 per cent more than leasehold counterparts (this can obviously vary based on location). This means that over a short investment horizon – such as five to 10 years – leasehold properties will almost always have the advantage.

(We’ll cover this in a follow-up article, on whether freehold properties are worth the premium. Follow us on Stacked for the update).

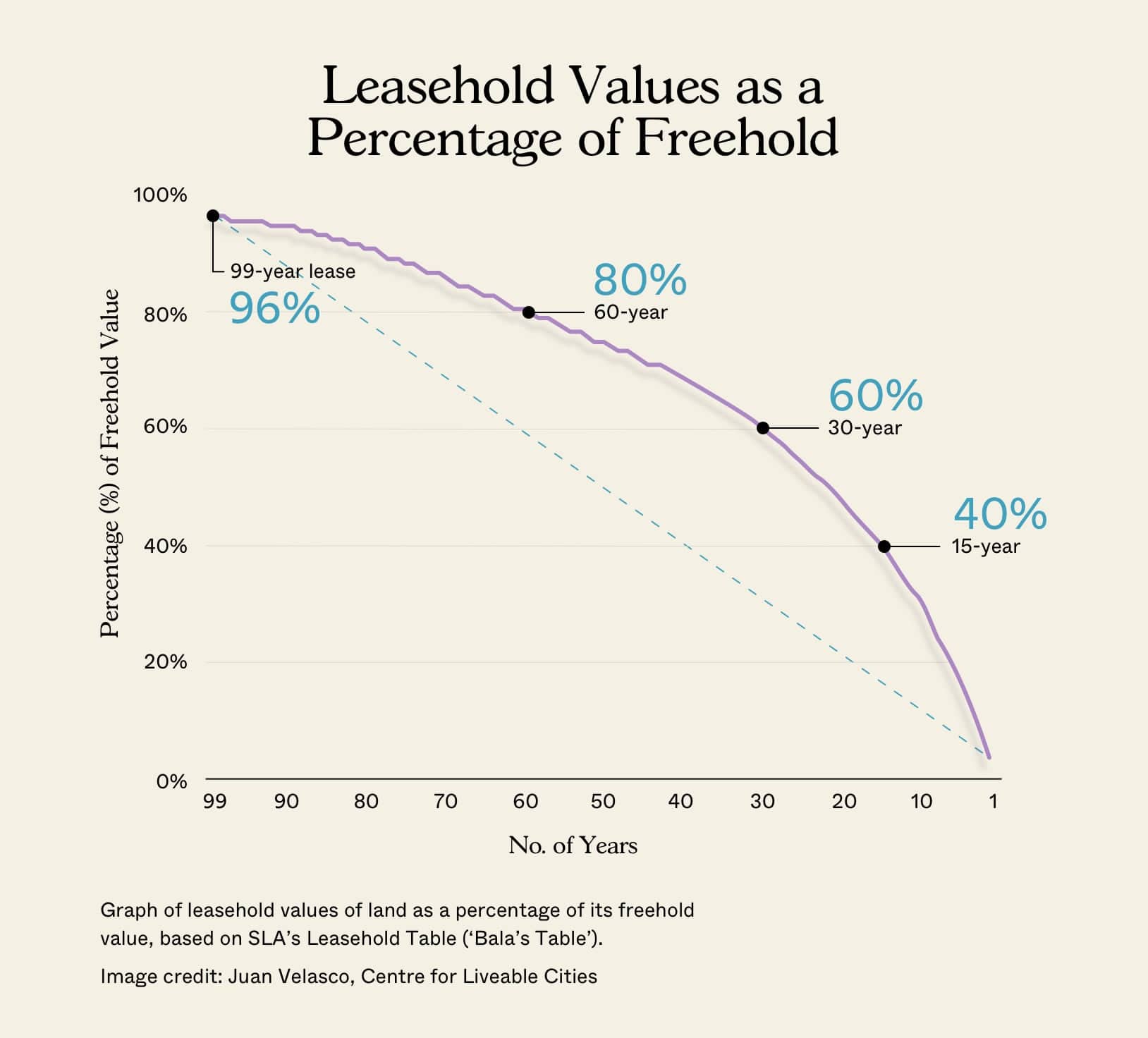

Conversely, freehold properties are less impacted by age, as they have no lease decay. An example of this can be seen in Bala’s Table, which is also quite similar to SLA’s land value table:

At around 60 years, for example, a leasehold project is worth 80 per cent of an equivalent freehold property. At around 30 years, a leasehold project drops to around 60 per cent of an equivalent freehold property.

So the longer a condo stands, the more advantageous/valuable its freehold status becomes.

But then, what happens if most condos end up going en-bloc at some point?

According to Bala’s Table, a leasehold property with 80 years left on the lease (i.e., it’s 19 years old) is still worth 91 per cent of its freehold counterpart. At 75 years (i.e., it’s 24 years old), it’s still worth 88.5 per cent of its freehold counterpart.

For an investor – making the assumption of an en-bloc sale at 19 to 24 years – it’s important to ask whether these numbers justify the 20 to 25 per cent premium for a freehold property.

On the flip side, certain leasehold properties may be more resilient than others as they may carry an en bloc premium. Generally, this varies depending on the development but it does affect both freehold and leasehold properties.

Leasehold properties that are not completely built-up or have en bloc potential due to potential transformation in the area may find willing buyers who pay a premium for that ‘en bloc potential’.

It’s hard to say exactly what it is, however, it is logical that certain older developments continue to attract buyers hoping to strike an en bloc deal in the future. Most buyers would be willing to pay more for a leasehold condo that hasn’t maxed out its GFA versus one that’s built within a 3-storey mixed landed housing area.

This helps to make the development more relevant and so, prices wouldn’t depreciate as fast. Such buyers usually buy for their own stay and don’t mind retiring there, but they also like the idea of hitting the ‘jackpot’ to boost their retirement plan in their later years.

This also affects owner-occupiers seeking their final home

If you’re older and settling into your forever home, you might think a freehold condo will do the trick. Unfortunately, as you can see from above, redevelopment prospects apply as much to freehold as they do leasehold (in fact there are far more freehold properties providing the data).

This is a serious concern: imagine settling into your “final home” at the near-retirement age of 55, then being forced to move in your 70s due to an en-bloc sale. Finding a replacement property is not so easy if home prices have risen, and your financing options are limited after retirement.

It may be that HDB flats (of which only four to five per cent of estates see SERS) are a better choice if you fear being forced to move.

This being said, we should consider the pace of en-bloc sales has been slowing

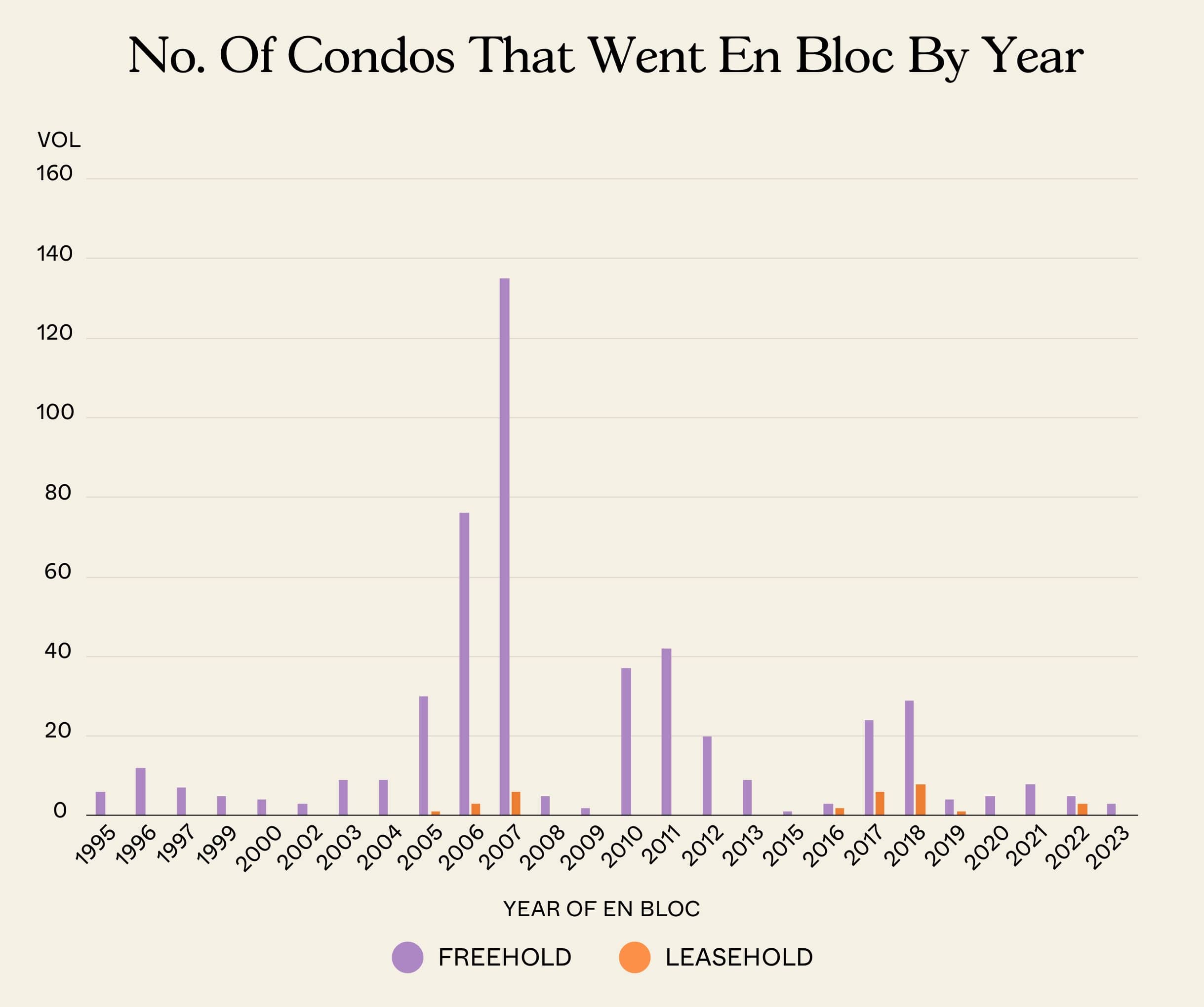

We can’t be certain if, going forward, we’ll continue to see en-bloc sales happening as early as 19 to 24 years. This is because historically, each en-bloc peak seems to be more diminished than the last.

Here are some en-bloc sale numbers over the past few years:

2007 remains unsurpassed as the ultimate year for collective sales, way beyond even the 2010 and 2017 en-bloc fever. This was the year when Farrer Court was bought for $1.3 billion, and redeveloped into D’Leedon. We saw 79 collective sales in total that year.

This period crashed to a halt in 2008/9, due to the Global Financial Crisis. The sharp surge that followed in 2010/11 was on the back of stimulus measures, such as rock-bottom interest rates, which fuelled renewed interest in the property market.

However, you’ll notice the peak was much lower than in 2007. We saw 37 and 42 collective sales respectively, in 2010 and 2011.

The next time we saw an en-bloc surge was in 2017. This time, it was mostly driven by large Chinese developers entering the market. However, the numbers were again weaker than the last peak. There were 30 collective sales in 2017, and 37 collective sales in 2018.

The main reason for this is government intervention: higher ABSD rates and a five-year time limit to sell have made developers more cautious. On the buyers’ end, higher ABSD rates for replacement properties also cool enthusiasm for en-bloc sales.

(E.g., if you own a second property that you bought when ABSD was seven per cent, but today buying a second property would have a rate of 20 per cent, you may be less willing to let the second property go in an en-bloc sale).

As such, it’s reasonable to conclude that residential properties may last longer going forward

A good case in point would be 2022. Along with many analysts and market watchers, we predicted a surge in en-bloc sales, as the last tranche of 2017 properties had been redeveloped. The anticipated surge never happened. Covid-19 did have something to do with that, but it’s now 2023 and we can see it’s still not happening.

That could also be due to the Government releasing more Government Land Sales (GLS) sites, which developers prefer. We explain it more here, but it all boils down to the much more straightforward process (no en-bloc delays from resident lawsuits), or having to tear down the existing buildings.

Besides ABSD rates, another subtle sign is how the government has rated buildings. The new CONQUAS score for developments – handed down by BCA – considers ease of downstream maintenance as a part of project quality.

Now if the government were happy to have new condos built and torn down every 20+ years, downstream maintenance wouldn’t be such a big priority. The increased focus on longevity implies they don’t want such short life cycles for projects.

For more on this topic, follow us on Stacked, as we’ll soon post a follow-up on whether freehold properties are worth the buy. In the meantime, we’ll also provide you with in-depth reviews of new and resale properties in the Singapore market.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Editor's Pick

Editor's Pick Happy Chinese New Year from Stacked

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Overseas Property Investing Savills Just Revealed Where China And Singapore Property Markets Are Headed In 2026

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News REDAS-NUS Talent Programme Unveiled to Attract More to Join Real Estate Industry

Singapore Property News Three Very Different Singapore Properties Just Hit The Market — And One Is A $1B En Bloc

On The Market Here Are Hard-To-Find 3-Bedroom Condos Under $1.5M With Unblocked Landed Estate Views

0 Comments