4 Reasons New Condos Are Launched At Higher Prices Than You Might Expect

April 6, 2025

In the Singapore property market, the general expectation is that you get a better price (i.e., early-bird pricing).. But whilst this is a common developer pricing strategy, it’s not universal; every now and again, you will come across a new launch where prices are quite flat throughout some sales phases. There are even cases where the price drops in later sales phases, to the disappointment of earlier buyers. Here are some of the reasons why, for certain properties, the developer chose to start higher:

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

Reason #1: It’s a small or boutique condo with a very low unit count

The traditional approach of gradually raising prices is used for most mid-sized and larger condos (500+ units and up). But in small or boutique condos, there’s sometimes no point to doing this; the developer may expect almost all the units to sell out at around the same time anyway.

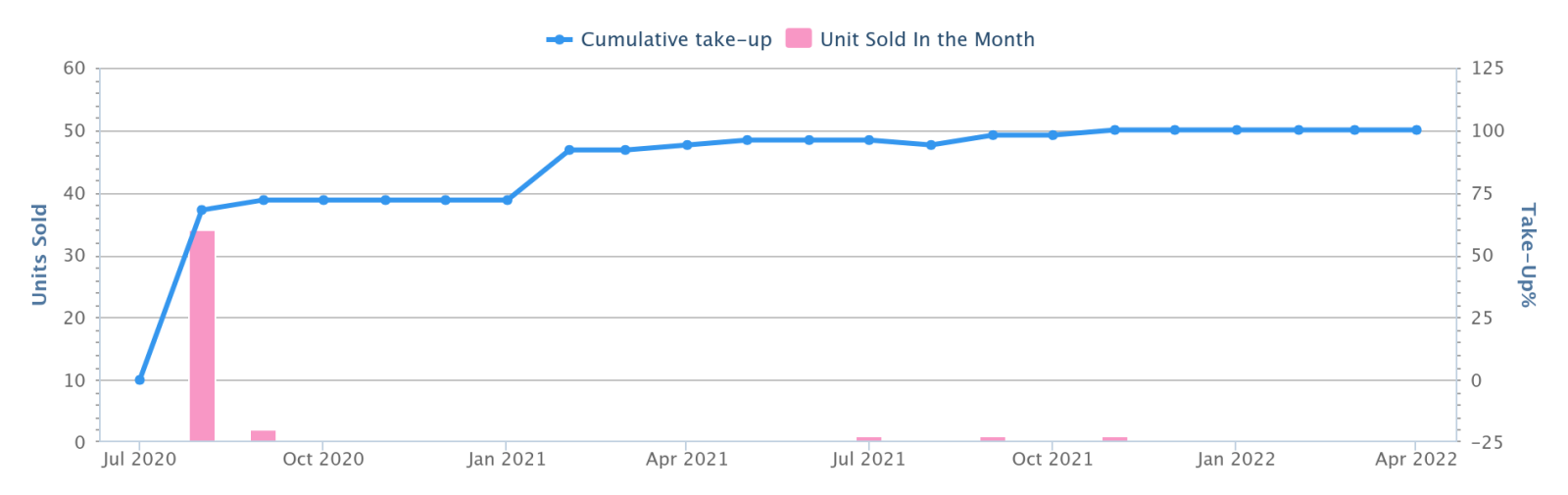

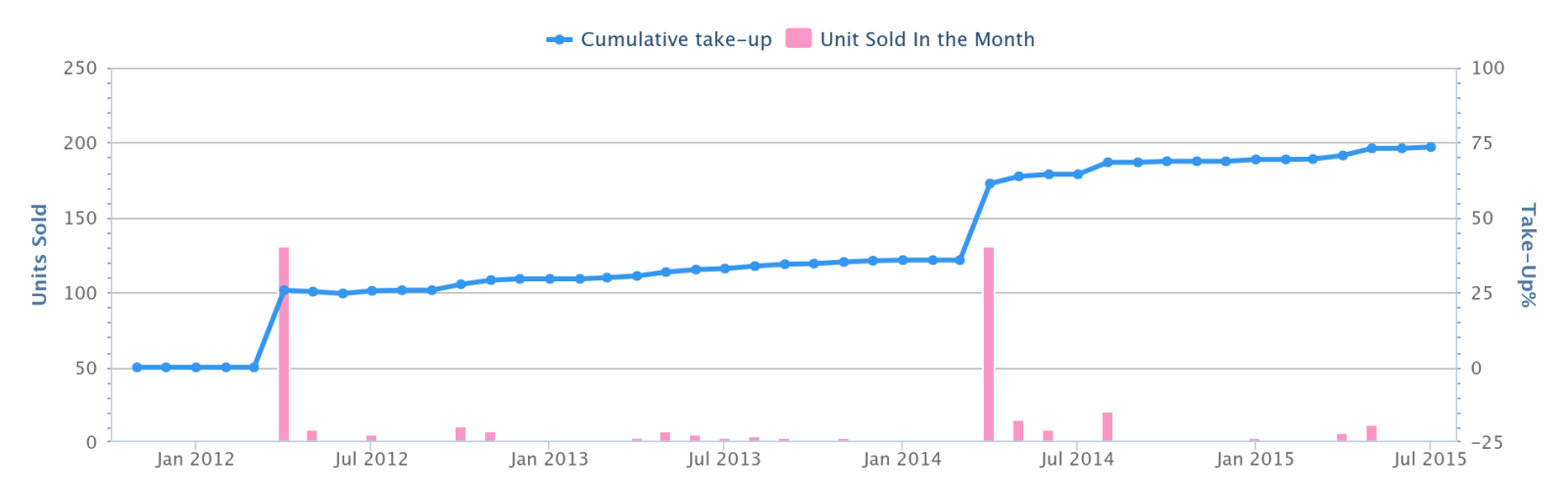

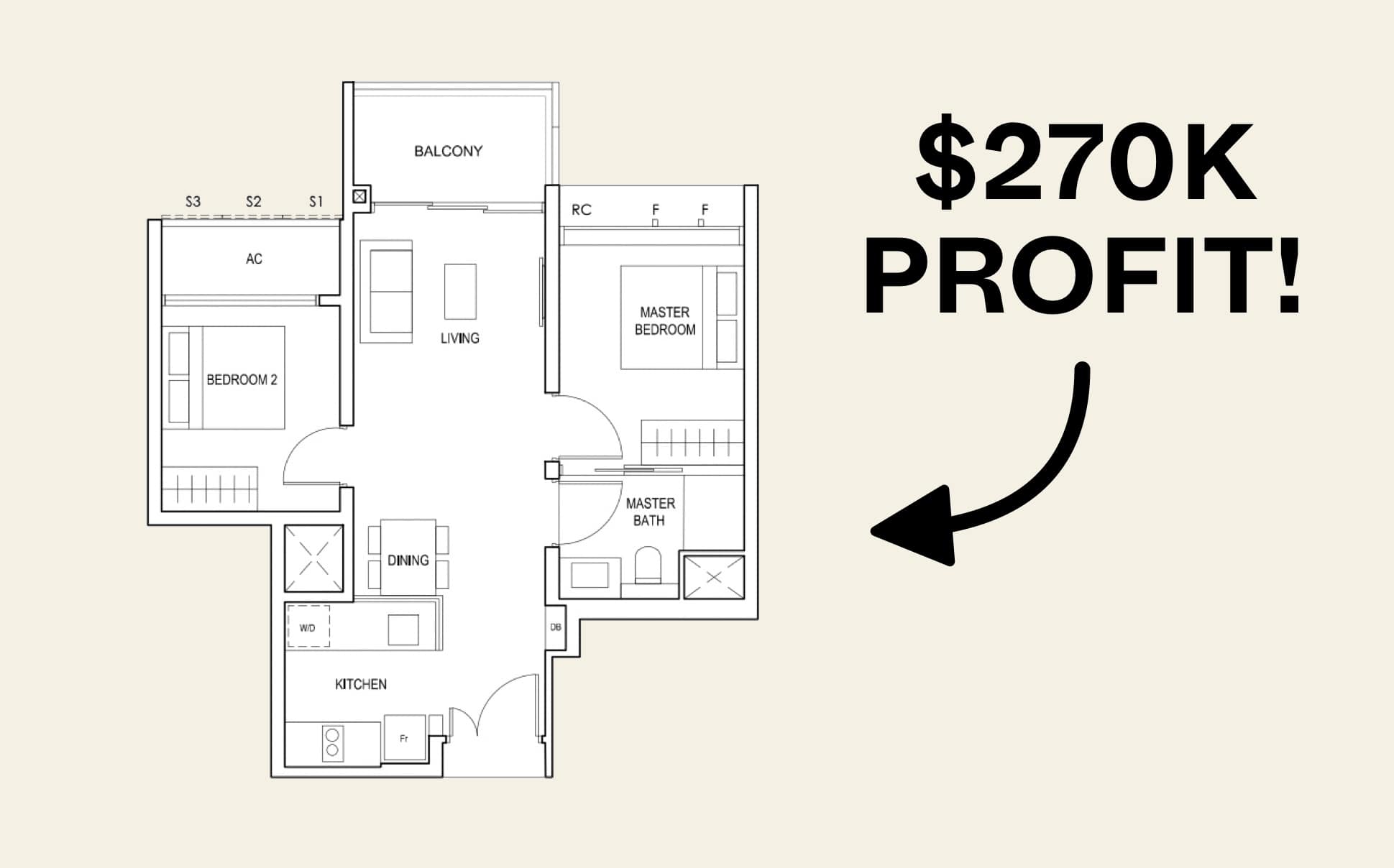

For example, consider NoMa, a freehold boutique condo in District 14. We can see that the developer didn’t start with big discounts:

(The small price fluctuations at the back are from single-unit transactions, and don’t reflect anything significant about overall project pricing.)

As we can see from the transaction volumes, the developer got it right:

There were only 50 units, which almost all sold in the same span; so there was no need to “entice” anyone with early bird discounts.

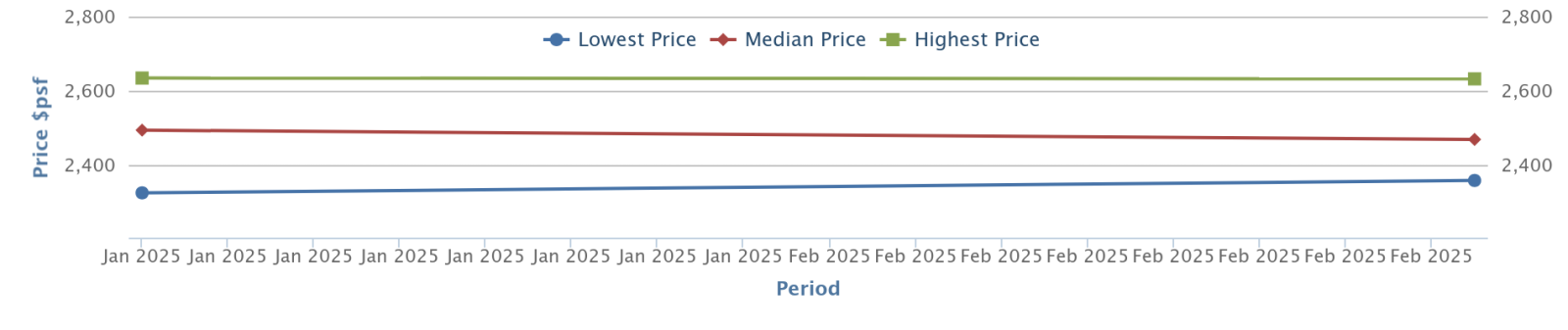

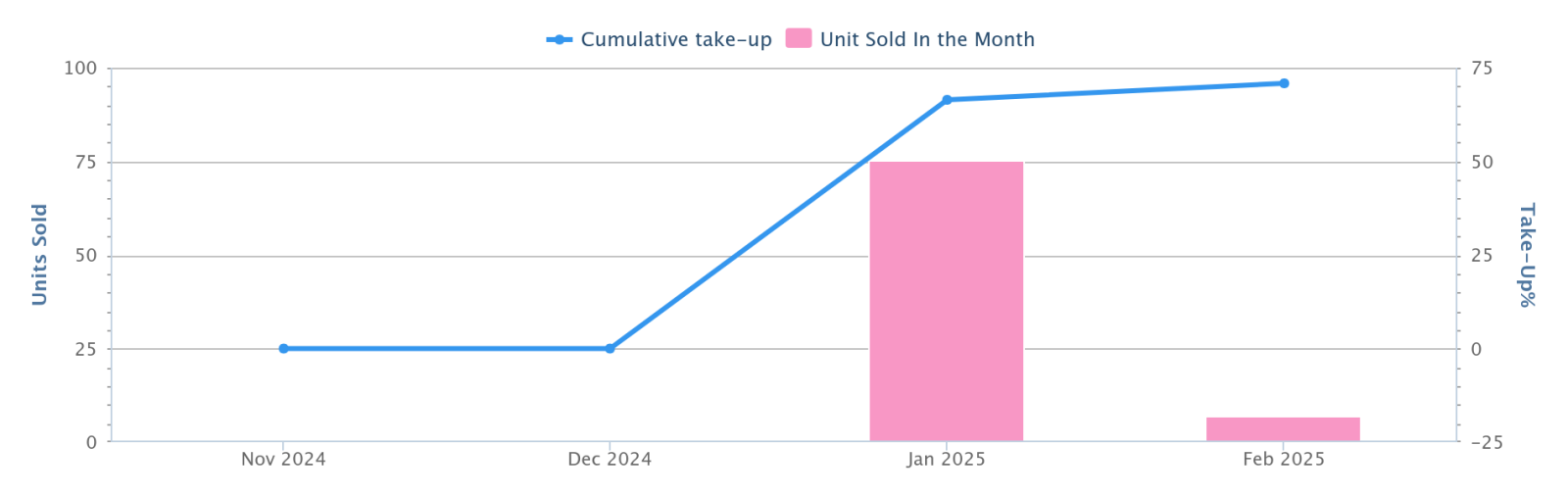

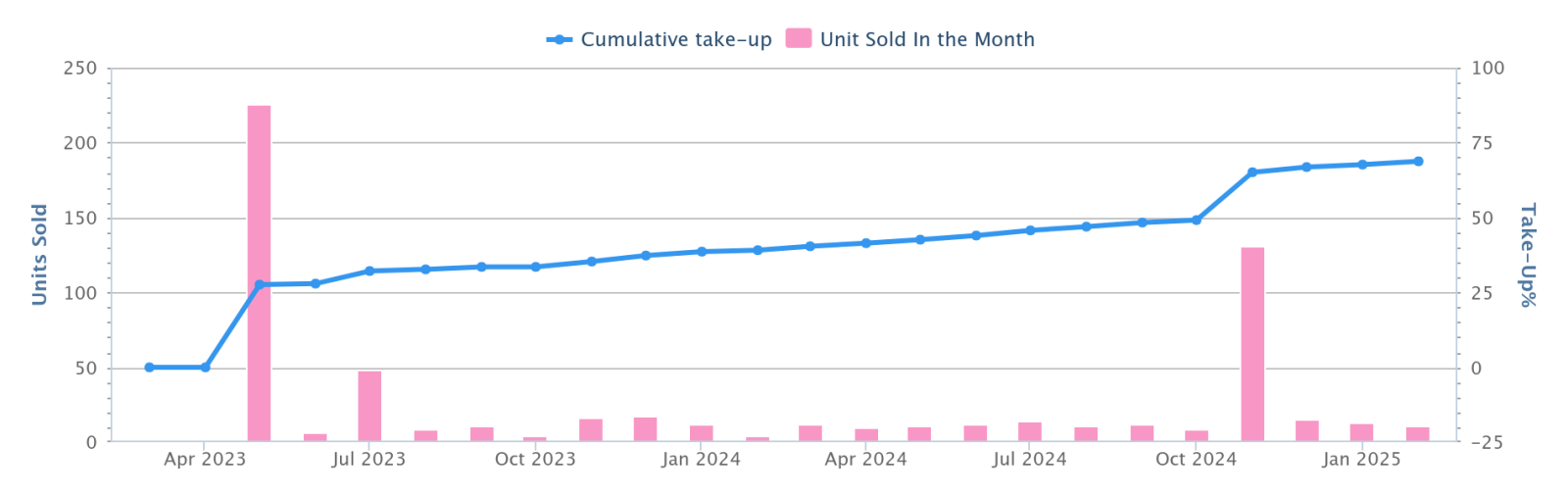

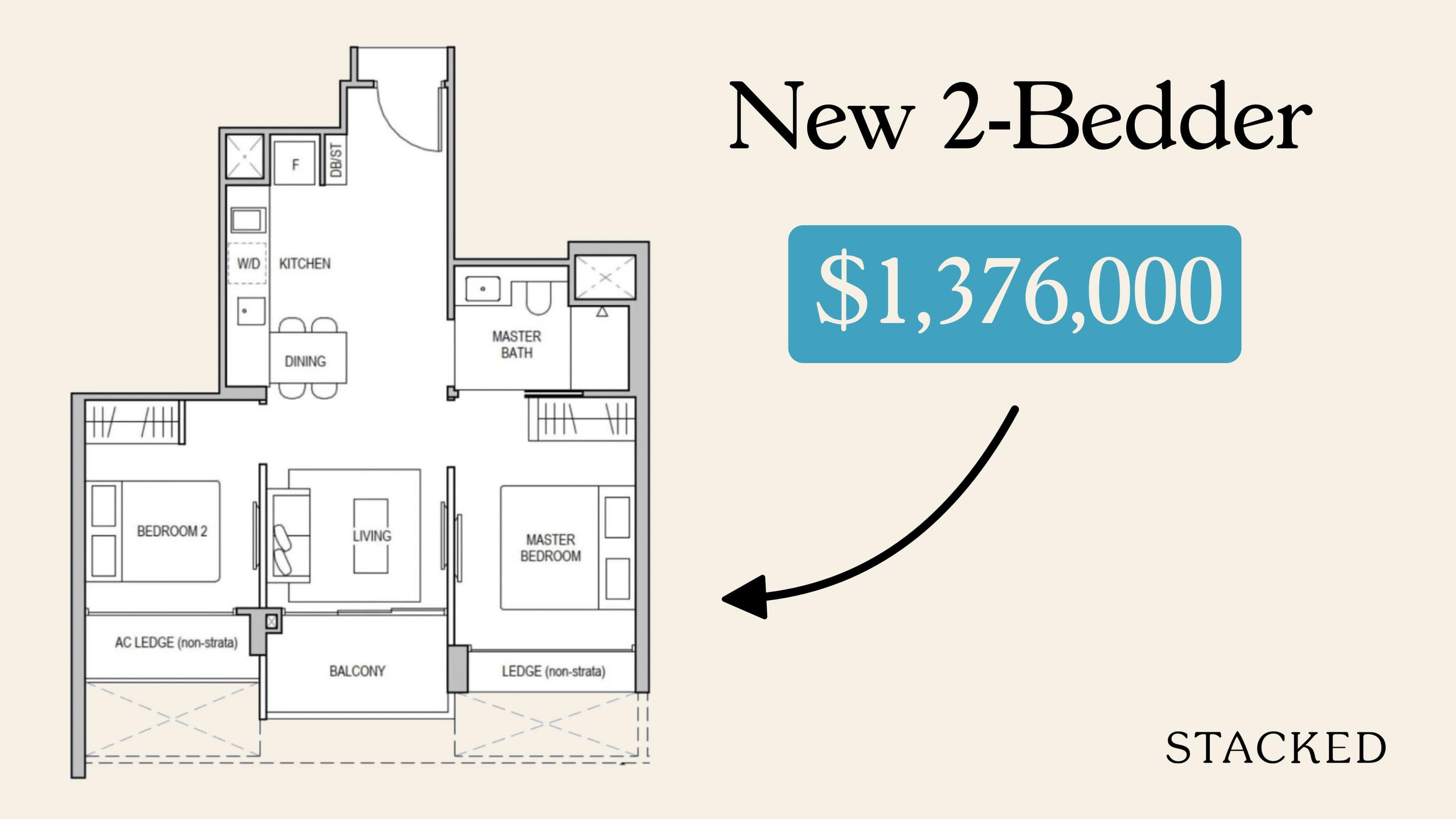

A more recent example is Bagnall Haus. There are only 113 units in this Bedok-area condo, of which around 71 per cent of the units have already been sold. Developer price movements are flat: there were no big discounts at the start, even though there were online comments about it being pricey:

Again, we can see it was mostly the right move from the developer: most of the units have already been sold, even without “loss leader” pricing strategies:

This is one factor to bear in mind, when purchasing small or boutique new launch condos. Unlike bigger developments, you might not see a discount for being among the first.

One realtor also told us boutique developments lean toward the luxury market, with projects like Meyerhouse, Boulevard Vue, Skyline, etc. The buyers of these projects are typically less price-sensitive, hence developers’ greater confidence in starting high.

Reason #2: Testing market acceptance

When a project is novel in some way, or there have been recent shifts in the market (e.g., new cooling measures were implemented just a while ago), it can be hard to pick a pricing strategy. While some developers may opt for caution and just price lower, others might do the direct opposite.

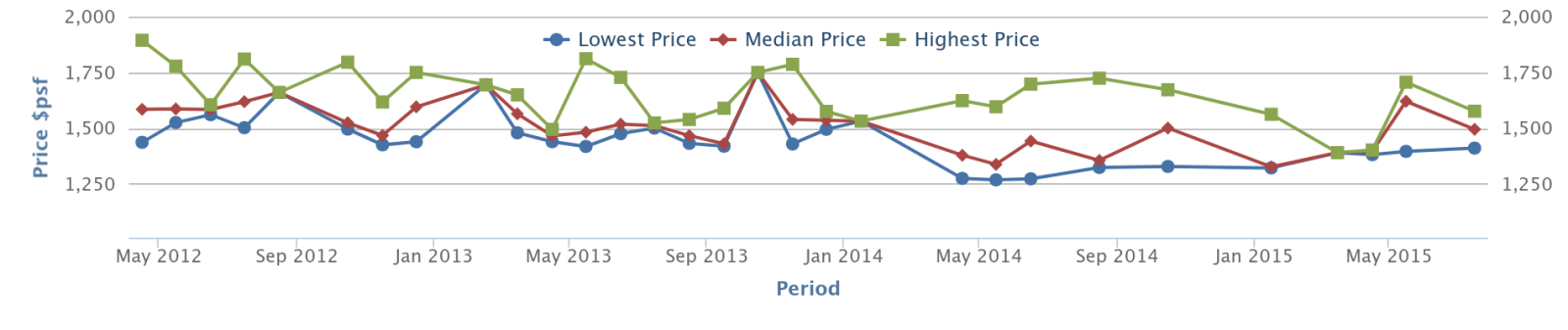

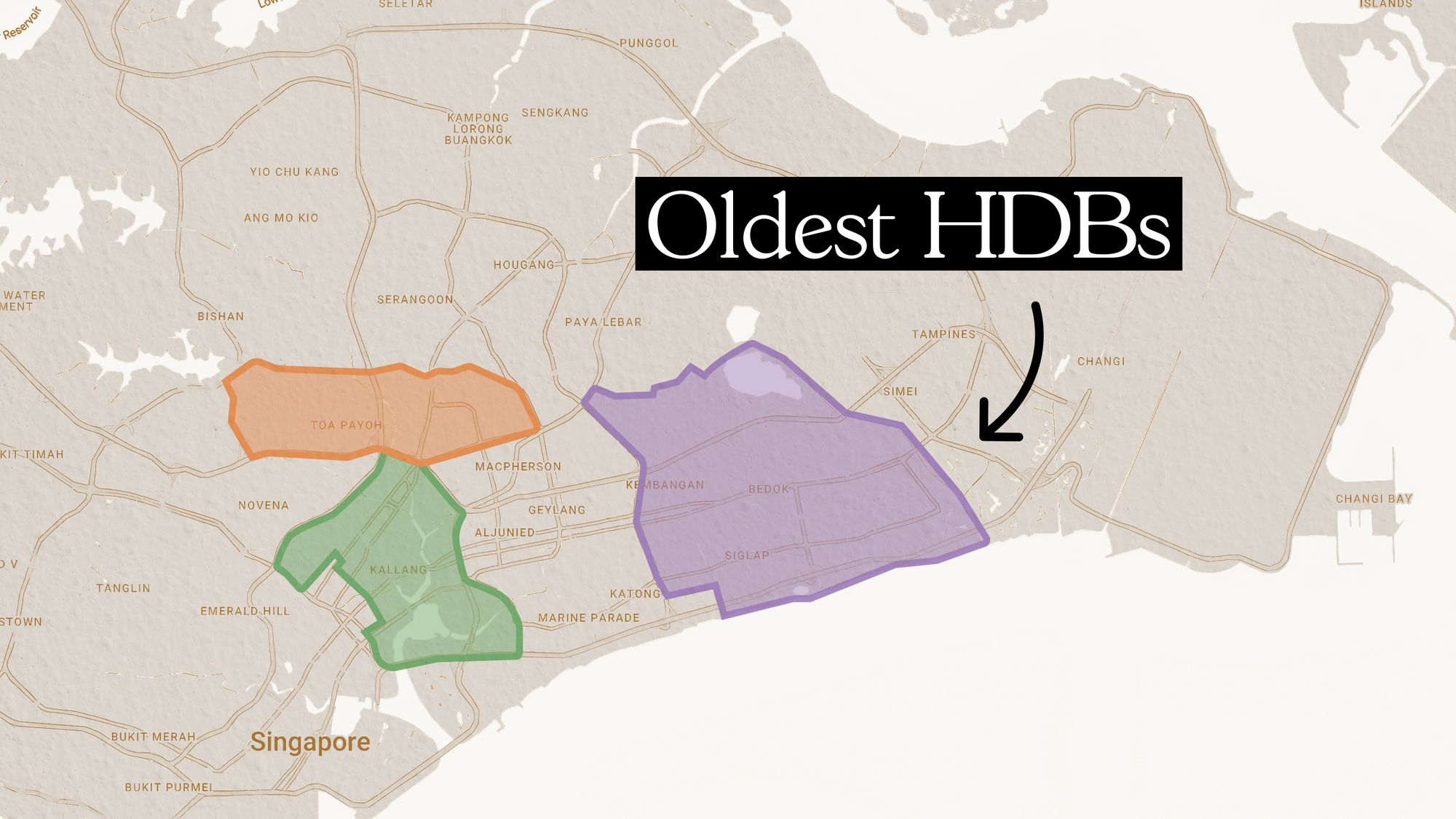

Sky Habitat in Bishan is a very good example of this: at the time of its launch in April 2012, Bishan was already an established hotspot – but for HDB flats. Would the demand translate to private non-landed homes in the same area?

Rather than be cautious, the developer played up the premium angle, and Sky Habitat launched one of the highest-priced OCR condos (at the time). The result was average, with around 70 per cent of the 509 released units sold on the launch weekend (there were 574 units in total). Subsequently though, sales stalled out, and the developer relaunched at a lower price:

You can see from the volumes that there were effectively two launch weekends. The second time around, the developer dropped prices to as low as $1,300 psf.

This ultimately panned out for the developer, as they managed to sell a good portion of the units at a higher price anyway: median prices at the first launch were $1,583 psf, while later on the median dropped to $1,493 psf.

The first batch of buyers probably aren’t too happy, but the second batch of buyers probably thought they were getting a great deal, given how much lower the prices had fallen; so the units moved easily.

If the developer had gone the other way (i.e., started lower), and then sales stalled out, they would have been in a conundrum: the last thing you want to do when buyers are losing interest is to raise prices even more. That said, it is possible that the developer didn’t intend this, and possibly thought the prices could go even higher – if so, they could well have intended to raise prices as normal later on.

More from Stacked

We Have $1.2m In Cash/CPF And Own A Queenstown HDB: Should We Keep Our HDB Or Sell To Buy 2 Properties?

Hi Stacked homes,

Reason #3: A nearby new launch is going to make them look affordable, when the pendulum swings back

Nearby new launches can help to sell an existing project, simply because buyers will actively compare them. A recent example of this is The Continuum, which we discussed in detail here.

The Continuum, being freehold, was pricier than competing new launches Tembusu Grand and Grand Dunman (and subsequently all three were undercut by Emerald Of Katong). We noted The Continuum’s price premium over its neighbours here, in a detailed comparison.

But knowing the state of the competition, why didn’t the developers use typical moves like bigger early-bird discounts, to drive momentum? The Continuum definitely saw slower early sales, with just 26 per cent sold at launch. The developer could have given early-bird discounts, and coupled with Continuum being freehold, it could have seen stronger initial sales.

But the developer didn’t have to do that, because the pendulum would swing back eventually

As the low-quantum one and two-bedders sold out at projects like Grand Dunman, only pricier, higher-floor three-bedders were left there. When the price gap between Grand Dunman and The Continuum then shrank, Continuum’s added advantage of being freehold came into force: buyers started to move back toward Continuum:

From the transaction volume, you can see how buyers started to come back by around November 2024. So The Continuum was able to sell its units anyway, without engaging in an early-stage price war.

Reason #4: Buyers tend to assume prices will rise later, so they may accept “full price” even from the start

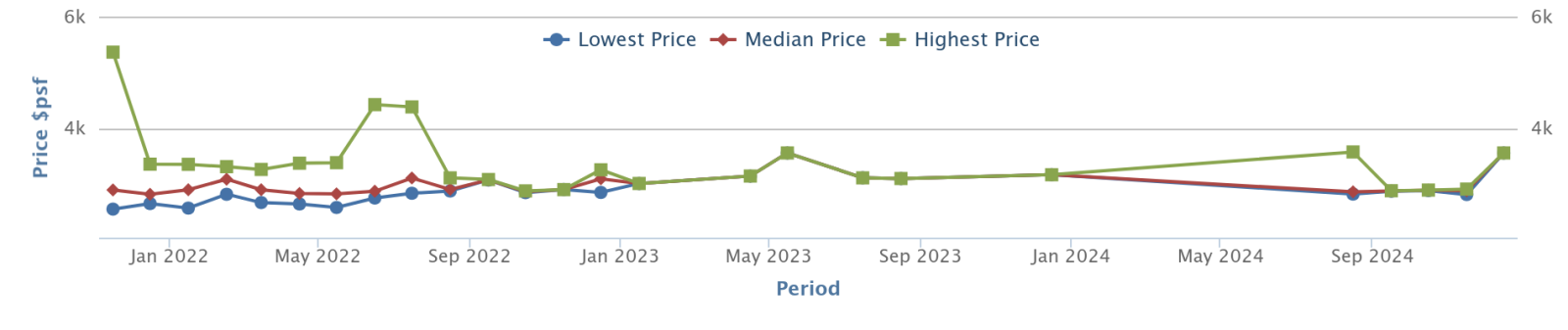

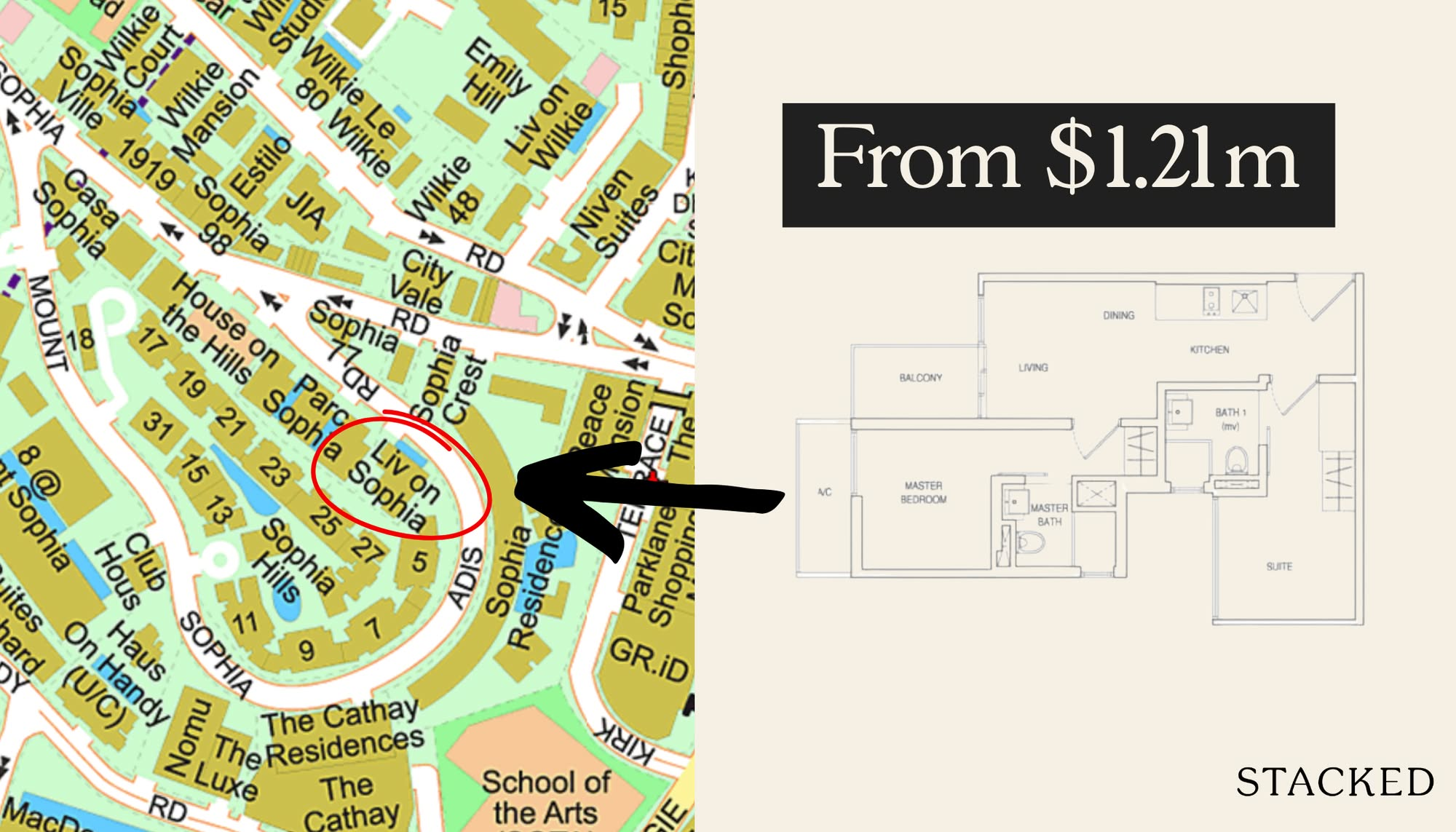

One of our on-the-ground experiences with this came with Canninghill Piers (former Liang Court). Due to the prestige of the location and project, the developer set a high price from the beginning, and they didn’t compromise till the end.

Barring the outliers (the highest priced single transactions at the start and end), the median prices at Canninghill Piers began at $2,887 psf, and at last check stood at $2,872 psf. And yes, the developer has managed to move units regardless: Canninghill Piers is almost entirely sold out at the time we’re writing this. So again, another example of a developer that didn’t need to give early-bird discounts.

During a conversation with one of the buyers, they mentioned that they found the price extremely high; but they were rushing to put down a cheque anyway. Why?

Their reasoning was that, if the price was high now, it would be even higher later. $2,887 psf was already painful for them. If it went up the next month, they would be priced out altogether. It is, after all, assumed that developers start lower, so the prices will climb. It wasn’t true for Canninghill Piers, but the developer won the psychological poker game with that particular buyer.

In this way, developers can leverage expectations to sell without early discounts.

As we can see, pricing is a matter of context

While there is a common way to price new launches (i.e., start low and go higher), this isn’t universal. We can see developers will vary the strategy based on many factors, such as the existing supply in the area, cooling measures, the target demographic, and much more. New launches don’t always start at lower prices, and buyers can’t assume better gains just because they bought earlier.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Frequently asked questions

Why are some new condos launched at higher prices than expected?

How does the size of a condo project affect its launch pricing?

Why might a developer choose to launch a new condo at a high price instead of offering discounts early on?

Can nearby new condo launches influence the pricing strategy of an existing project?

What psychological factors can lead buyers to accept full prices from the start?

Ryan J. Ong

A seasoned content strategist with over 17 years in the real estate and financial journalism sectors, Ryan has built a reputation for transforming complex industry jargon into accessible knowledge. With a track record of writing and editing for leading financial platforms and publications, Ryan's expertise has been recognised across various media outlets. His role as a former content editor for 99.co and a co-host for CNA 938's Open House programme underscores his commitment to providing valuable insights into the property market.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Property Market Commentary

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Property Market Commentary Why Some Old HDB Flats Hold Value Longer Than Others

Property Market Commentary We Analysed HDB Price Growth — Here’s When Lease Decay Actually Hits (By Estate)

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News These 4 Freehold Retail Units Are Back On The Market — After A $4M Price Cut

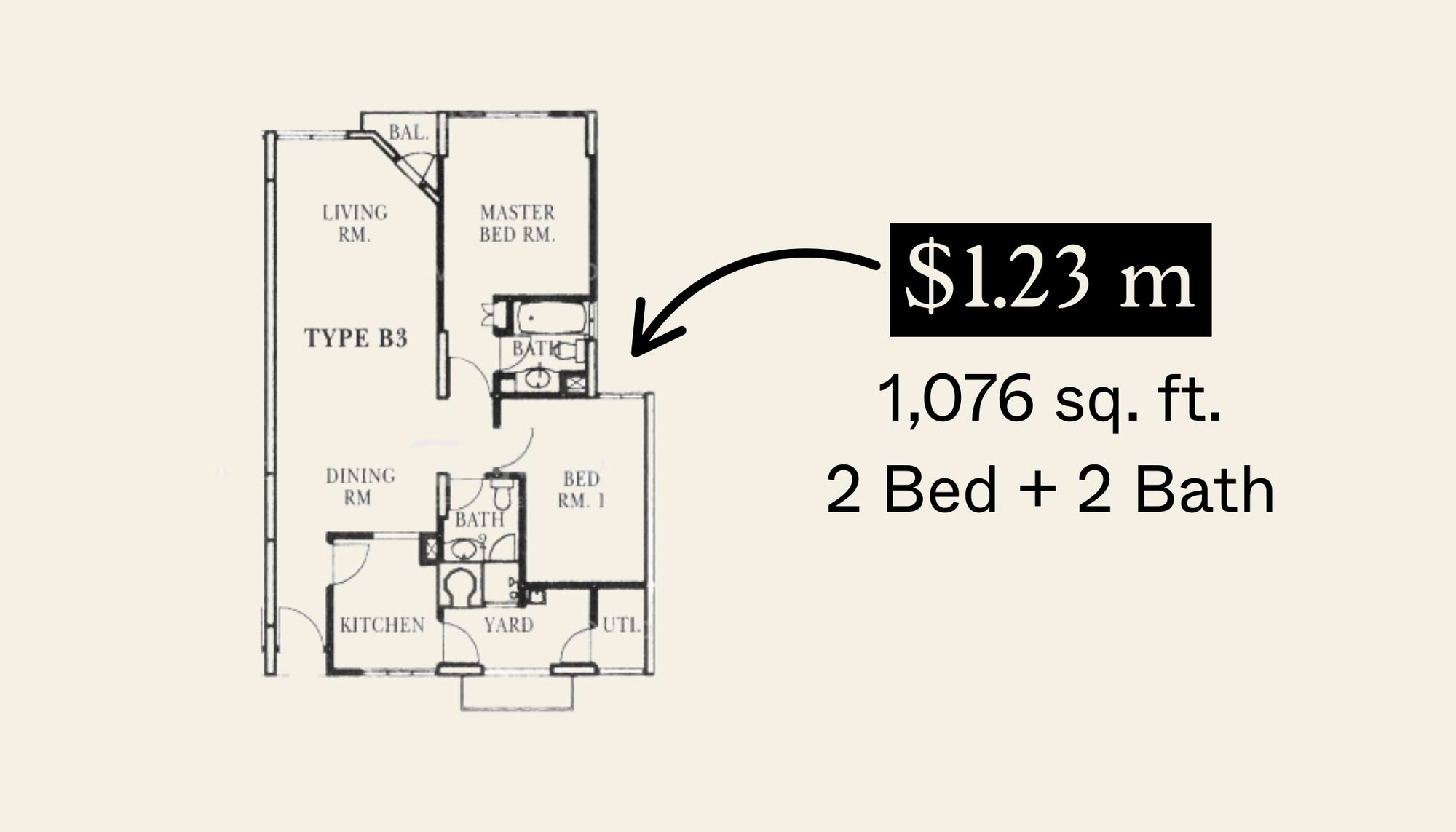

Pro This 130-Unit Boutique Condo Launched At A Premium — Here’s What 8 Years Revealed About The Winners And Losers

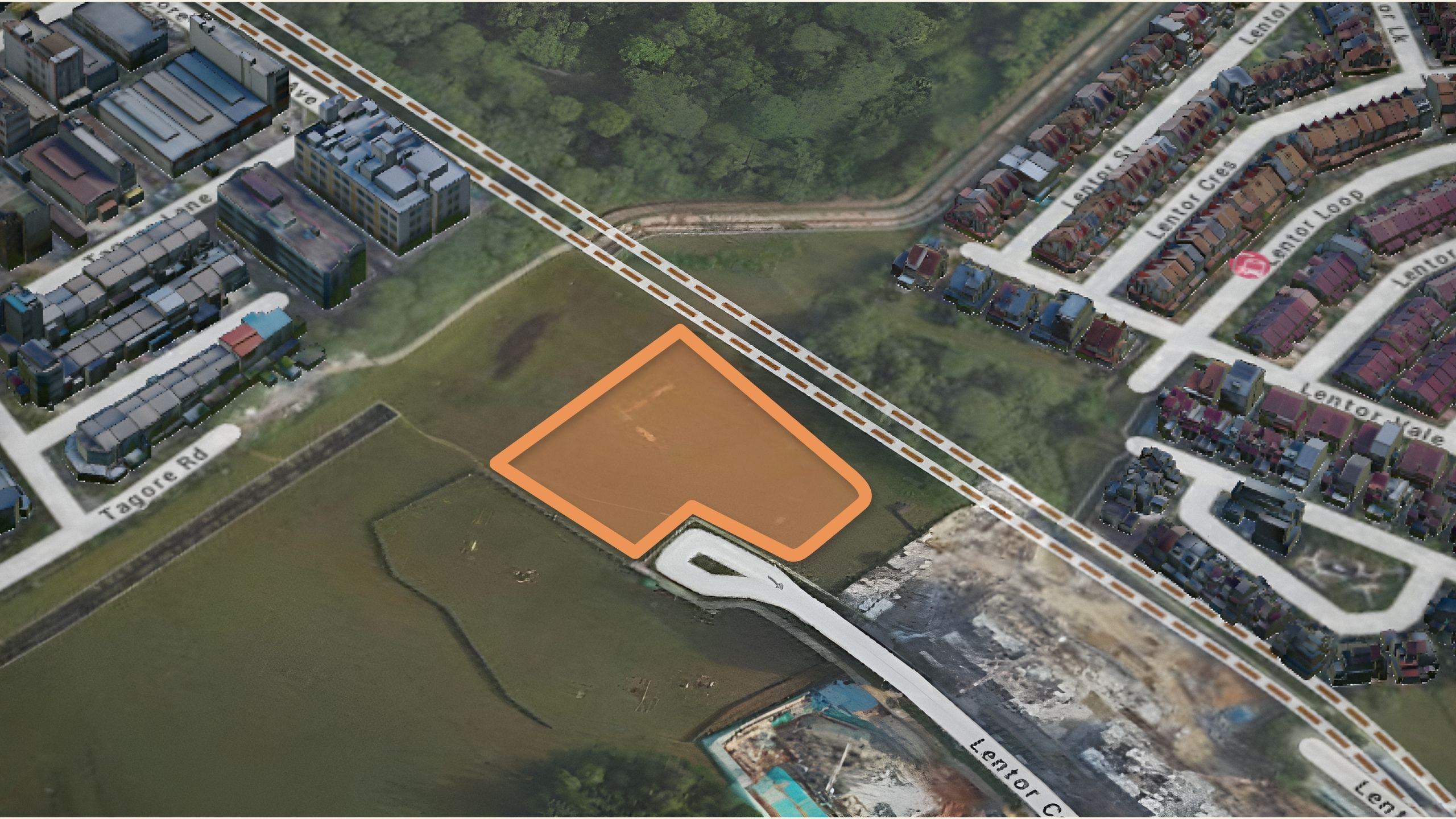

Singapore Property News New Lentor Condo Could Start From $2,700 PSF After Record Land Bid

0 Comments