10 Old Iconic Private Apartments In Singapore In The 1970s/80s: A Conversation With Finbarr & Samantha

July 11, 2022

Did you know that high-rise apartments have actually been accused of many unpleasant outcomes? Chief of these are themes like fear, dissatisfaction, stress, behaviour problems, suicide, poor social relations, reduced helpfulness, and hindered child development. (Adapted from Robert Gifford, The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings)

While it might sound like it’s a bit of an exaggeration given that the majority of Singaporeans are living in high-density apartments (be it private or public), due to the land constraints that we have. There was a time when low-rise and landed living was the rule – and high-rise, communal living was something that had to be introduced to the population.

Due to the issues mentioned above, developers faced significant challenges in introducing this type of communal living to the middle and upper classes. The 1970s and the 80s were a time when condominiums were still literally on the rise – when architects were still pushing a new way of collective living.

But what do you think happened to those who courageously took the plunge into this new way of living in those decades?

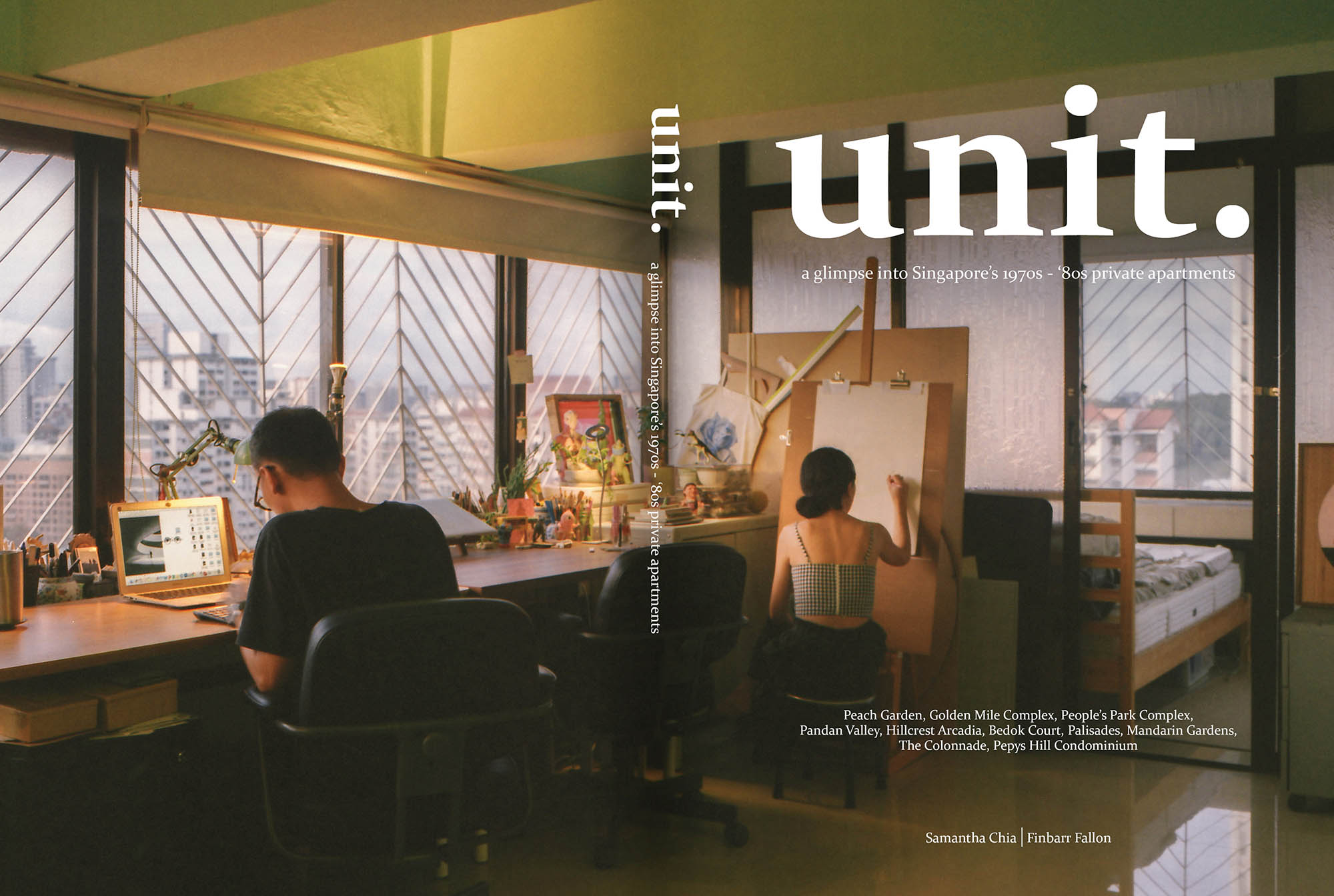

Finbarr Fallon, an architectural photographer and artist, and Samantha, an urban planner with a background in architecture, took on the undertaking to document the life, then and now, of those who decided to live in these private apartments.

Their book, “UNIT.” a glimpse into Singapore’s 1970s – ’80s private apartments, is set to become available by the end of July 2022. We’re happy to be able to interview them and get some insightful knowledge even before the book launch.

Here’s the conversation we had with them.

So many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

1. If you had to choose one of these apartments to live in, which would you choose and why?

Samantha quickly replied that it would be Bedok Court.

She loved how the condominium was designed to create a sense of community, and she thinks it’s been quite successful in this aspect. “There’s something about the scale of the apartment blocks and how they’re arranged around a central courtyard,” she said. For those who are unaware, Bedok Court’s central courtyard houses recreational facilities.

When it comes to the layout of the unit, Samantha liked how the apartments were designed with ample open space. She said that each of them has a generous patio in the front and at least one balcony at the rear.

“The family that we interviewed used their patio for their creative projects,” she said, “and that’s something that I can see myself doing.”

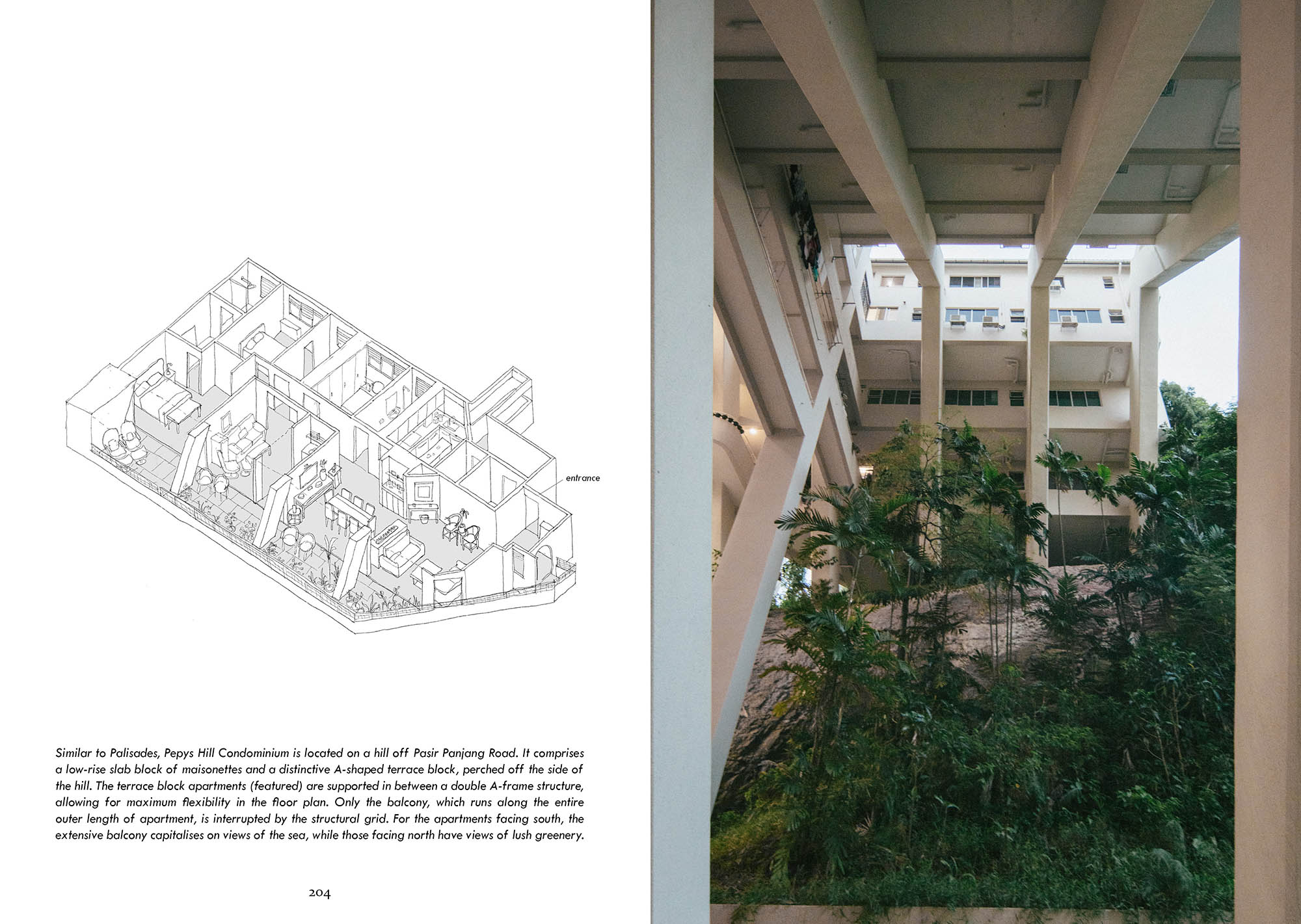

Finbarr, on the other hand, chose Pepys Hill, which is the apartment they visited.

“I like it for the same reasons the residents chose to live there,” he said. The apartment faces Kent Ridge Park, where it has an amazing view of the trees, as well as a quiet environment, which Finbarr loves.

“To me, it’s an oasis in an otherwise hectic city.”

He also prefers Pepys Hill because it’s a relatively small condominium, with the size of the development and the number of residents both contributing significantly to the overall feeling.

2. Many of these older apartments have certain quirks that may be hard to overcome for some people. Why do you think that some of these were built this way?

Finbarr and Samantha were not sure about the “quirks,” but they both agreed that residents they met were so willing to open up their homes to them because they loved the apartments they were living in. One of the questions they had when they first started their projects was if these 1970s and 1980s apartments would translate well into modern living today. The welcoming response they experienced from the residents gave them a clear answer.

When it comes to design considerations, they said to keep in mind that private high-rise housing was a relatively new concept at that time.

Architects of these apartments needed to take into consideration the elements required to influence their target market. They had to understand how to influence affluent homeowners into trading the exclusivity of living in a landed property with living in proximity to strangers.

Split levels and large terraces for planting are examples of methods some of the architects used, introducing design features in the apartment that were closely associated with landed housing. On the contrary, others focused on what was unique to these condominiums, such as the communal facilities and open spaces within the apartment grounds.

3. Do you have any advice for homeowners looking to purchase a home in these older apartments?

In all honesty, they said they’re definitely not the people to turn to for such advice. They confessed that they don’t have the relevant training or skill set, especially when it comes to financial matters.

However, they can share the commonalities they gathered from every family that they visited. Each household chose their apartment because it matches their lifestyle and needs. They were able to make their apartment truly their own – an attitude applicable to any type of home purchased regardless of age.

4. While you’ve seen many apartments in Singapore, was there a particular development that surprised you the first time you went there? If so, any reason why?

Palisades was what Samantha answered. “I almost thought that we were at the wrong place because we could only see what we later realised was the car park podium.”

The apartments at Palisades were designed to terrace down the slope of the hill so you can’t see any of them from the road. Samantha said that it made the experience of visiting the apartment, as well as riding the funicular lift, more intriguing. “We always do a bit of research beforehand, but sometimes it’s difficult to imagine how our experience would be until we actually visited the building and the apartment.”

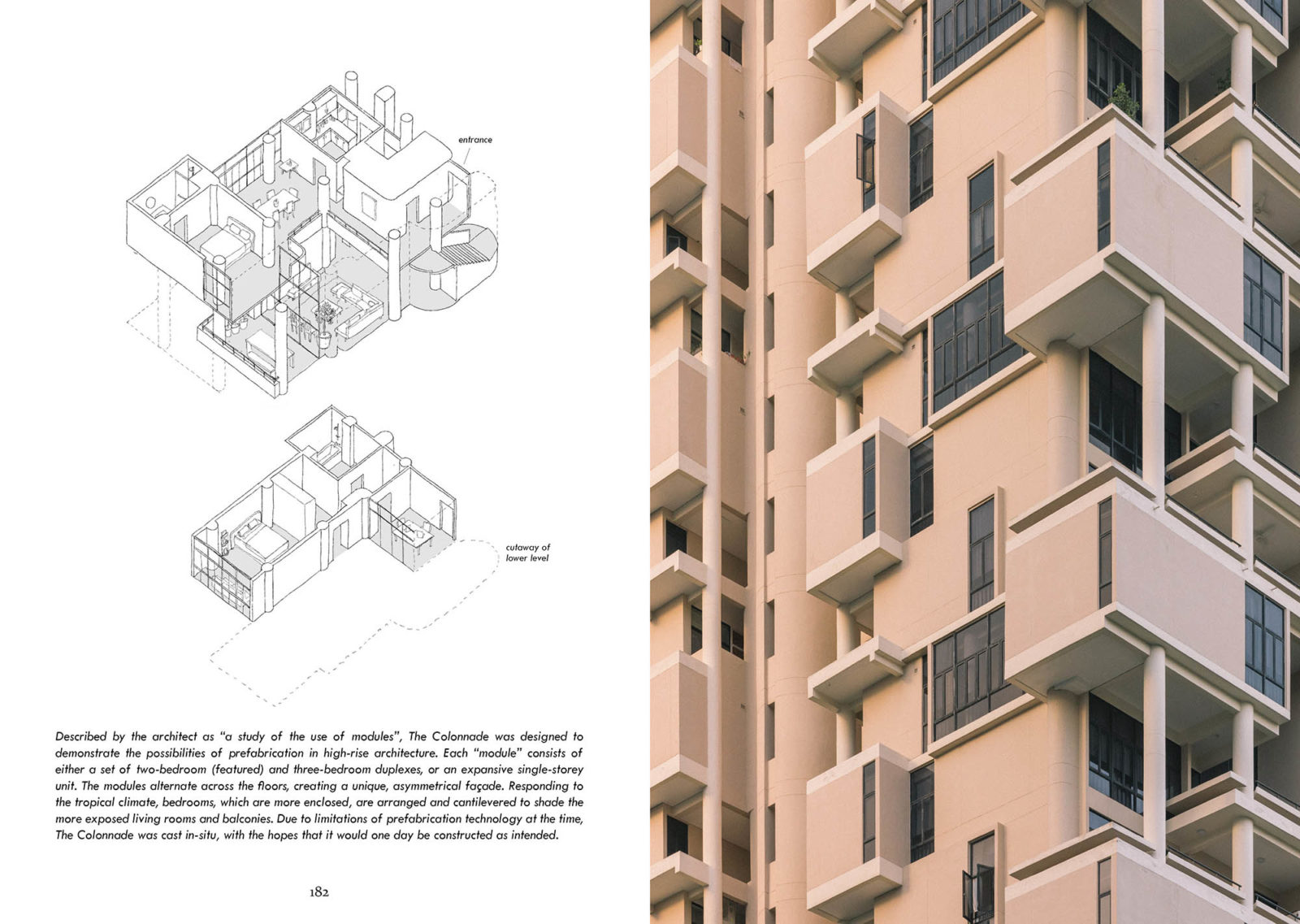

For Finbarr, though, it would be The Colonnade because of its architecturally interesting form. He said that the geometry looks complex, but it’s actually the same module repeated and alternated across the floors. Paul Rudolph, The Colonnade’s architect, was fascinated with the ideas of megastructures and the use of prefabrication as a modern construction technique – which he showcased in this apartment.

More from Stacked

How Does Pinnacle@Duxton Keep Producing These Million-dollar Flats?

Pinnacle@Duxton just saw a record-breaking $1.232 million transaction, for a five-room flat. It’s the highest price to date for an…

“Having said that, the building is actually cast in-situ because of the limitations of prefabrication technology at the time, but it still captures that spirit of innovation and aspiration of a modern city,” Finbarr added.

5. Which was the toughest apartment to photograph? If there’s one, could you let us know the reasons why?

Finbarr replied that rather than one specific apartment, the challenge permeated all the apartments they visited. The day they visited them was their first time getting to know them and seeing their apartments. “What was tough was that we didn’t know any of the residents beforehand, so we needed to think on our feet a lot,” he elaborated. “We had to understand the spaces and they were lived in quickly.”

Contrary to when Finbarr typically shoots residential interiors for commercial clients, they did not want to overdo curating the images. He had to photograph the apartment as it was lived in and, as much as possible, tried not to move the furniture around. “It was a very different approach,” Finbarr said, “and the challenge then came in how to capture or tell stories of the residents who lived there.”

6. You’ve taken so many architectures and interiors in Singapore. Is there a common thread in local design that you’ve noticed?

“That’s difficult to say because the challenges that architects faced in the 1970s and 1980s might not be the same challenges that they encounter today,” Finbarr answered.

But he said one thing stands out to both him and Samantha, who had considerable training in architecture. Architects who are mindful of Singapore’s tropical climate always consider how to respond to the heat and rain. These planners and builders always maximise cross-ventilation, be it in the past or present – a very significant factor, especially with today’s global warming.

7. You once did a thesis project on Subterranean Singapore that was exhibited in Archifest 2016. Now in 2022, do you see Singapore moving towards that direction?

Finbarr replied that while land scarcity is a fundamental issue that underpins Singapore’s development, it’s important to think vertically in terms of how space is used or created. “But having said that, Subterranean Singapore is, at the end of the day, a speculative piece.”

8. The focus of “UNIT.” is on the old architecture of Singapore and its charms, from the perspective of someone who also shoots many future-forward commercial architectures. Do you see any intersections in the new that draws from the old?

“For me, it’s the spirit of innovation that ties the two together,” Finbarr responded. He explained that while thinking of these older apartments as charming these days, they were actually pushing boundaries on what homes should be like at the time.

Finbarr said that future-forward architecture runs in the same vein. “It’s a marathon, with each generation of architects pushing boundaries for the next generation to take over.”

9. Golden Mile Complex is one of the highlights featured in “UNIT.” and to the relief of many photographers and architecture aficionados in Singapore, it has been recently awarded Conservation status. Do you think that Singapore is “doing it right” in terms of conserving architectural history and culture?

Both Finbarr and Samantha stated that “UNIT.” is not a commentary on the status of conservation in Singapore. What they wanted was to document the lived experience of these apartments objectively – both the good and the bad. For them, the book is about raising awareness as to the significance of Singapore’s post-independence buildings. It also talks about architecture in a way that would be more accessible to the public.

“We’ll leave it to the experts, such as DOCOMOMO Singapore or Singapore Heritage Society, to comment on Singapore’s conservation efforts,” Samantha added.

10. After featuring these older projects, is there something that you feel newer developments in Singapore are missing?

Samantha said that it’s really difficult to compare the two “simply because the contexts in which they were built differ so much.” With older apartments, it’s usual to have unique layouts because architects were experimenting with what high-rise living should look like.

Today, high-rise living has become commonplace. “We’re seeing a lot of standardisation in the building industry,” she said, ” and apartment layouts appear to be becoming more similar across developments.”

“We can’t say that these changes are good or bad, only that they are a reflection of our times,” Samantha stated.

11. What do you hope to see in residential architecture in Singapore moving forward?

Finbarr and Samantha said that “UNIT.” shows us how the home can take on many different forms of expression. Each apartment they visited was indeed personal and unique to the family living in them. They both hoped that whatever form Singapore’s residential architecture takes on in the future, it will always allow the home to truly take place.

Catch A Glimpse Of The Life In These Classic High-Rise Condominiums

Discover more about how residents lived in the decades immediately following Singapore’s post-independence – particularly in private condominiums. “UNIT.” is the latest work to date by authors Finbarr Fallon and Samantha, which documents how these old-school spaces – built about half a century ago – continue to function even in contemporary times.

For those interested, you can pre-order UNIT. a glimpse into Singapore’s 1970s – ‘80s private apartments at finbarrfallon.com/unit.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Sean Goh

Sean has a writing experience of 3 years and is currently with Stacked Homes focused on general property research, helping to pen articles focused on condos. In his free time, he enjoys photography and coffee tasting.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Homeowner Stories

Homeowner Stories We Could Walk Away With $460,000 In Cash From Our EC. Here’s Why We Didn’t Upgrade.

Homeowner Stories What I Only Learned After My First Year Of Homeownership In Singapore

Homeowner Stories I Gave My Parents My Condo and Moved Into Their HDB — Here’s Why It Made Sense.

Homeowner Stories “I Thought I Could Wait for a Better New Launch Condo” How One Buyer’s Fear Ended Up Costing Him $358K

Latest Posts

Pro Why Some Central Area HDB Flats Struggle To Maintain Their Premium

Singapore Property News Singapore Could Soon Have A Multi-Storey Driving Centre — Here’s Where It May Be Built

Singapore Property News Will the Freehold Serenity Park’s $505M Collective Sale Succeed in Enticing Developers?

0 Comments