When My Gong Gong With Dementia Went Missing: Are Singapore’s Neighbourhoods Prepared For An Ageing Crisis?

September 17, 2024

Just the other day, I received a distressing call from my panic-stricken auntie asking for help.

“Cheryl, your gong gong is missing! He left home alone without me knowing and I don’t know where he is now. I need help looking for him”.

My heart sank at the gravity of her words. My granddad has severe dementia, is almost a hundred years old and as with the elderly, is vulnerable to falls and injuries.

My entire family was mobilised immediately. The mission was simple – we just wanted to get gong gong safely home.

Thankfully, we found him within an hour. He was sitting with a kind samaritan outside a nearby FairPrice (a place he loved to visit with my grandma when she was still around). The passerby found him wandering alone and offered to keep him company while she looked for help.

As someone who firmly believes in the idea that “how we shape our cities will eventually shape us”, this incident sparked my interest in understanding how our built environment is ready to support Singapore’s growing elderly population, especially those living with dementia.

That said, Singapore’s ageing population and some of its imminent problems are not an unfamiliar concept to the general public. However, what many might undermine is its impact on our society.

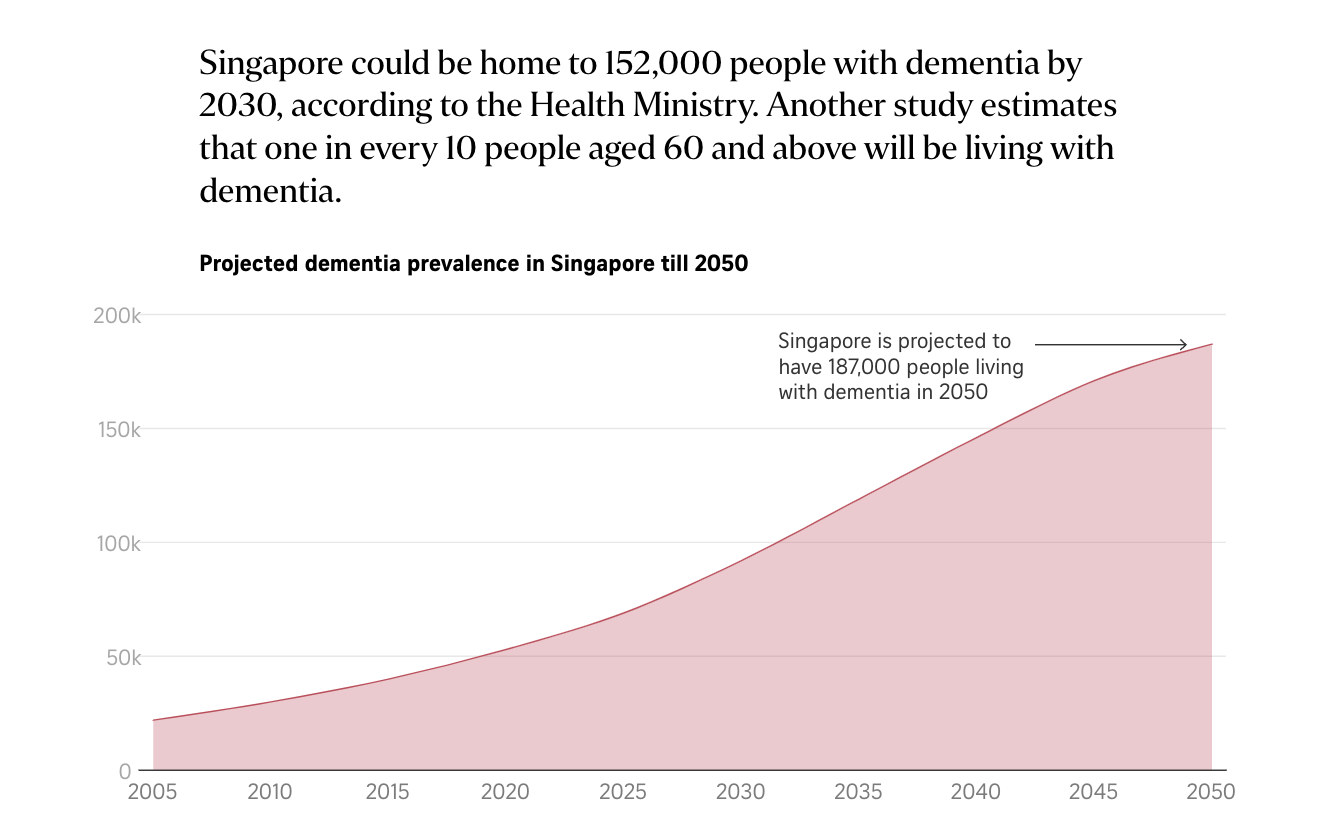

Research has shown that, by 2030, 1 in every 4 Singaporeans will be 65 years old. Further studies have also noted that Singapore could be home to 152,000 people with dementia, which means one in every ten people aged 60 and above will be living with dementia.

As more of our families and loved ones enter (or have already reached) this stage of life, preparing for an ageing population is no longer just a NIMBY issue – it’s a collective responsibility.

In this article, I aim to raise awareness about the impact of dementia on our ageing society and explore how Singapore can become a safer, more inclusive place for everyone.

Because ageing isn’t simply about growing older—it’s about living well.

And we all have a role to play. Here’s what I’ve discovered.

Many readers write in because they're unsure what to do next, and don't know who to trust.

If this sounds familiar, we offer structured 1-to-1 consultations where we walk through your finances, goals, and market options objectively.

No obligation. Just clarity.

Learn more here.

The Birth of Dementia-Friendly Towns (DFTs)

Dementia Friendly Towns are Singapore’s modern-day response to managing the nation’s growing group of elderly living with dementia.

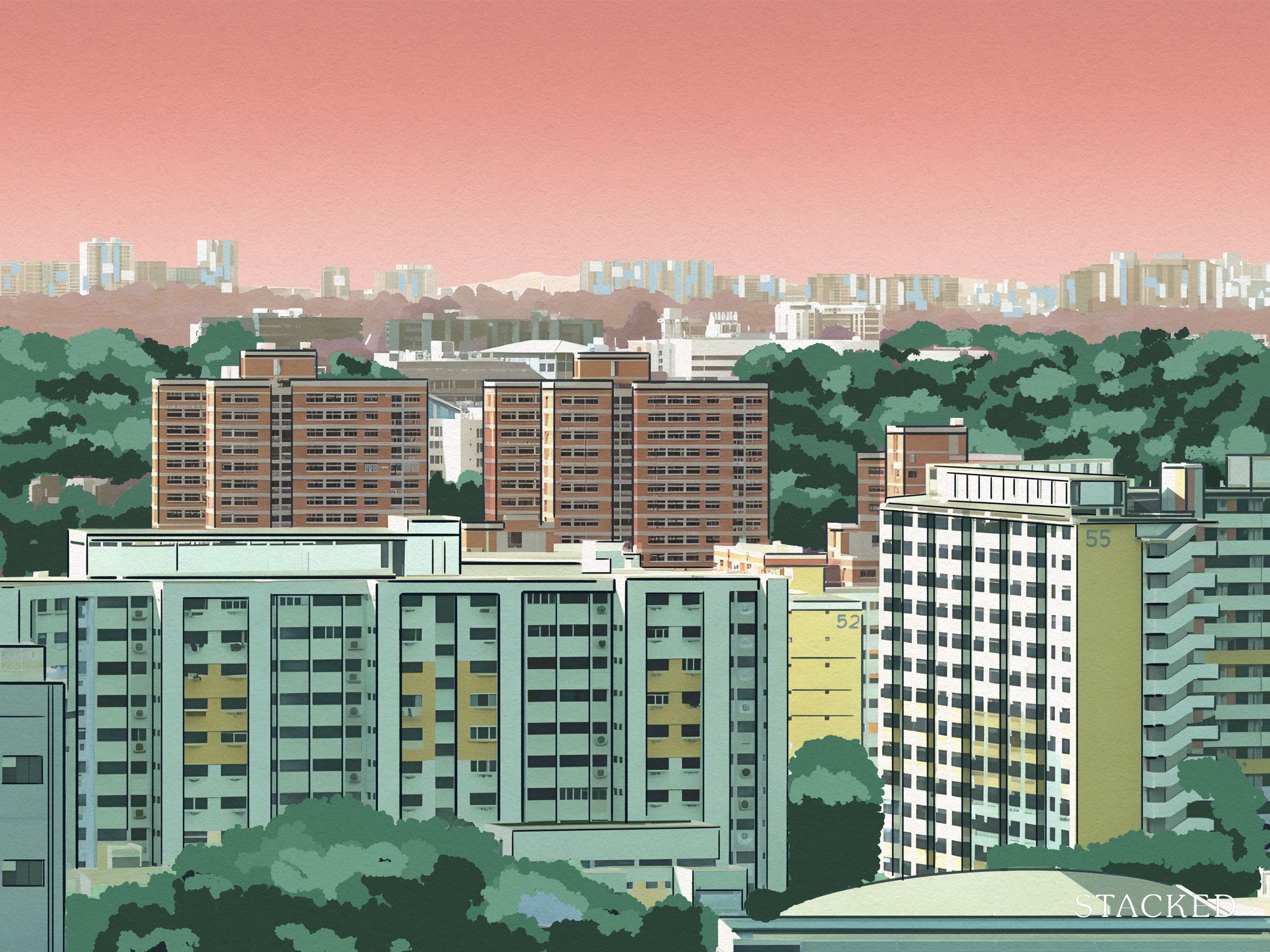

As certain neighbourhoods in Singapore have an elderly-heavy demographic profile, this makes dementia a more pressing issue in those estates. Some of the earmarked estates include mature areas like Kebun Baru, Woodlands, Yio Chu Kang, Toa Payoh and Marine Parade.

What I found (after hours of scouring the internet) was that there are exactly six design principles that make a neighbourhood “dementia-friendly”. The key purpose is to make a positive difference in the daily lives of affected residents in subtle ways.

The principles include Familiarity, Legibility, Distinctiveness, Accessibility, Comfort and Safety.

Here’s a quick run-through of all six guiding principles:

- Familiarity: Small, incremental changes to the environment help dementia patients recognize and navigate their surroundings independently.

- Legibility: Clear path networks and public information displays, such as colours and images, make environments easier to understand.

- Distinctiveness: Landmarks and unique structures serve as visual cues and orientation points.

- Accessibility: Convenient, walkable routes to essential services encourage dementia patients to venture outdoors.

- Comfort: Sensory-friendly environments, including green spaces, help reduce agitation and anxiety.

- Safety: Features like separated cycling and walking lanes, wide footpaths, and adequate lighting minimize risks for dementia patients.

But to really understand how this plays out in reality, I had to tour one of the DFTs and see how useful these guiding principles are in bettering the lives of the residents.

Touring Marine Parade & Marine Terrace: One of Singapore’s Dementia-Friendly Towns

Since my gong gong lives in Marine Parade and it was my childhood home ground (I lived with my grandparents when I was younger), it was a natural choice for me to explore this neighbourhood.

Prior to this, I had no idea that Marine Parade was a dementia-friendly town, so it was heartening to see that measures were in place for the elderly living in the area. Yet, I was surprised at how little has been done to spread awareness for this cause – barely anyone I knew who lived there was informed that such measures were in place.

My tour started at Marine Terrace, where many of the dementia-friendly installations in the neighbourhood are concentrated. These include several designated Go-To Points (GTPs), wayfinding murals and elderly-focused community services (which I’ll go through in greater detail later in the tour).

By and large, the built environment looked quite the same as I remembered it to be a decade ago.

The most noticeable addition was undoubtedly the opening of the highly anticipated Marine Terrace MRT Station, which ensued other upgrades such as newer bus stops, wider pedestrian pathways and underpass linkways.

What I had assumed would be a welcomed change was met with unexpected feedback when I spoke to a long-time resident of the area. She shared that the transformation of the built environment had been quite drastic, and many elderly residents seemed to struggle with adapting to it.

Lately, she’s observed an increasing number of elderly residents wandering alone (though she’s unsure if they are lost) and wonders if this is a growing challenge of familiarity in a neighbourhood with a high elderly population.

Apart from the newly added train station, the neighbourhood also went through a revamp in the paint works (for those unaware, it’s standard for HDBs to get a fresh coat of paint every seven years under the Town Council’s Repair and Redecoration works).

There was a deliberate choice to use various shades of blue and white for the different blocks, perhaps to aid in wayfinding for the residents in the neighbourhood. Another visual sign to improve wayfinding was the visibly enlarged block numbers on the respective buildings.

The block numbers were strategically painted to be visible at eye level and eye-catching from afar to aid with way-finding.

When I spoke to my aunt (who lives in the neighbourhood with my gong gong), she mentioned that these enlarged numerals on the blocks were very helpful in aiding both of them to get around and wait for each other. This, I would say, was a well-received change in the neighbourhood.

More from Stacked

The Hidden Costs of Hiring a “Cheaper” Agent In Singapore

At first glance, fixed fee agents can seem like an easy win. After all, who wouldn’t want to save on…

One of the more eye-catching additions would also be the Peranakan-themed murals to serve as an added form of way-finding in Marine Terrace.

Not only do these vibrant murals brighten up the neighbourhood, but they also act as distinctive landmarks, offering a helpful visual cue for those who may need extra assistance with directions, all while preserving the rich Peranakan heritage of the area.

I found another cue here through the artwork of the Singapore River in a popular resting spot within the estate.

Naturally, landmarks like wet markets and food centres would be helpful in re-positioning those confused with their bearings. To many, the Marine Terrace market is one of the most well-known landmarks within the area.

It is a popular spot for residents and those staying nearby to get food, groceries and other necessities. However, the downside is that it is always noisy and crowded, which might be overtly stimulating to those living with dementia.

As many of the elderly living in Marine Terrace require financial assistance, some community-driven solutions include the Value Meal @ Marine Parade initiative.

Stores that are part of this initiative ensure fixed prices on their food menus or offer meals under 3 Singapore Dollars to help residents cope with the effects of inflation and the rise in the cost of living.

This 24-hour Giant Express Supermarket is another stalwart in the community and it is a popular spot for many elderly residents to ‘enjoy the aircon’ while buying groceries (as quoted from my granddad’s neighbour).

As this Giant supermarket is located within a comfortable walking distance of most blocks in the area, it plays a crucial role in promoting accessibility (one of the six design principles) for those living with dementia.

The GoodLife Makan would probably be the biggest tell-tale sign that Marine Parade is an elderly-friendly and dementia-ready neighbourhood.

An elderly-focused recreational centre situated at a void deck of one of the HDB blocks, GoodLife Makan features a communal kitchen and open eating spaces. It has a simple but tricky aim – to reconnect the stay-alone elderly to the wider community and facilitate social interactions by leveraging Singapore’s rich food culture.

Needless to say, the noise and visible crowd in GoodLife Makan on a Monday afternoon was a clear sign that it is a well-received addition to the neighbourhood fabric.

The open garden, manned by some of the community members, presented an inviting ambience to the centre. The see-through communal areas and wide tables are also conducive for the residents to mingle, have their meals and find opportunities to integrate themselves into society.

To the fast-changing community, these public facilities might indicate signs of obsoletion but for the existing residents, the features are still crucial to their day-to-day lives.

That said, I notice that the overall built environment of the neighbourhood is still relatively unchanged from my childhood days, which goes to say that these dementia-friendly alterations are not revolutionary (and can be easily overlooked).

Some of the changes (like the bigger block numbers and wayfinding murals) positively impacted the lives of some residents I spoke to. Not only that, the enhanced footpaths helped aid safer journeys too.

And while it’s heartening to know that Singapore is taking a step in the right direction, I think more can be done to make these spaces more tailored to the elderly and those living with dementia.

One suggestion I got from speaking to the residents included changing the floor materials as they can get slippery on rainy days, making it hard and dangerous for the elderly to get around alone.

Another proposition included adding more prominent and brightly-coloured resting points for dementia-ridden elderly to sit and rest while acting as a meet-up point for them and their caregivers.

Above all, I think what would truly make a difference is nurturing stronger community support. Most people I knew who lived there had yet to learn that Marine Parade was categorised as a DFT.

If the community could be more involved and sensitive to vulnerable residents, these DFTs would be much safer and more inclusive. Residents, like you and me, can be more observant of lost or confused neighbours and lend a helping hand when required.

This was probably what truly helped my gong gong get back home so quickly – all because the samaritan was aware that the neighbourhood was more prone to those living with dementia and kept her eye out for anyone who needed help.

Final Thoughts

In the end, my gong gong’s brief disappearance wasn’t just a personal scare but a reminder of the larger challenges we face as a society. Nurturing dementia-friendly communities is not just an act of compassion, it is a necessity for Singapore’s rapidly ageing community.

As we’ve seen through the examples of existing DFTs, the rise of such communities is a step towards the right direction. However, much more still needs to be done to allow our loved ones to age gracefully. As the saying goes too “how we treat the elderly is how we prepare the world for ourselves.”

By raising awareness and pushing for more inclusive spaces, we can ensure that Singapore remains a safe and supportive place for everyone, regardless of age or ability.

At Stacked, we like to look beyond the headlines and surface-level numbers, and focus on how things play out in the real world.

If you’d like to discuss how this applies to your own circumstances, you can reach out for a one-to-one consultation here.

And if you simply have a question or want to share a thought, feel free to write to us at stories@stackedhomes.com — we read every message.

Cheryl Teo

Cheryl has been writing about international property investments for the past two years since she has graduated from NUS with a bachelors in Real Estate. As an avid investor herself, she mainly invests in cryptocurrency and stocks, with goals to include real estate, virtual and physical, into her portfolio in the future. Her aim as a writer at Stacked is to guide readers when it comes to real estate investments through her insights.Need help with a property decision?

Speak to our team →Read next from Editor's Pick

Editor's Pick Happy Chinese New Year from Stacked

Property Market Commentary How I’d Invest $12 Million On Property If I Won The 2026 Toto Hongbao Draw

Overseas Property Investing Savills Just Revealed Where China And Singapore Property Markets Are Headed In 2026

Property Market Commentary We Review 7 Of The June 2026 BTO Launch Sites – Which Is The Best Option For You?

Latest Posts

Singapore Property News Why Some Singaporean Parents Are Considering Selling Their Flats — For Their Children’s Sake

Pro River Modern Starts From $1.548M For A Two-Bedder — How Its Pricing Compares In River Valley

New Launch Condo Reviews River Modern Condo Review: A River-facing New Launch with Direct Access to Great World MRT Station

0 Comments